New Celtic team takes over. Three directors ousted as #17.8m rescue package pledged. The new team takes over with a promise

March 1994

A new regime was installed late last night at Celtic after the extraordinary boardroom coup. It broke a century of control for one family, but promised to restore the club to former glories.Scots-Canadian Fergus McCann and Glasgow businesman Brian Dempsey, whom head the takeover consortium, however, warned that no magical wand exists and that supporters must be patient: the depth of the club’s deep-rooted problems has still to be fully plumbed.

They argued Celtic’s financial plight was such that they had moved to prevent the club from collapse, and would require time to take prudent rather than rash decisions on the way ahead.Vice-chairman David Smith; club secretary and largest shareholder Chris White; and director Michael Kelly have been ousted — their 23% shares in the club sold to the rebel group, bringing to a close a long and acrimonious power struggle.The departure of Mr White, son of former chairman, the late Desmond White, means one of the three family dynasties which have ruled over Celtic for 106 years has gone.

The takeover was officially confirmed at 10.45 last night, some 13 hours after the seven-strong board was called to an emergency meeting because of a 24-hour deadline set by the club’s bankers to resolve its perilous financial position.The Bank of Scotland had threatened receivership unless action to reduce the reputed #9m overdraft was taken.Club chairman Kevin Kelly, who has retained his position, announced, all matters have been resolved, including the three resignations. He thanked them for their contributions made to the club over the years.Mr Kelly, cousin of ousted Michael, said he had no problems withworking with the new board. He denied there was any split in the family,and added: ”There has to be a way forward and a new era. This is what happened.”Mr McCann, the new chief executive, now has at least 50% control, but reiterated an earlier promise to relinquish such power within five years.Along with Mr Dempsey, he warned he would be a hard task master because they were not men with small ambitions.

Sources told The Herald that the ousted directors will each receive #100 a share — that is #200 a share less than offered last month by another rebel pact not involved in yesterday’s deal.It means Mr White, who has 14.25% of the club’s shareholding, will receive nearly #300,000 compared with almost #900,000 if he had quit earlier.Mr Smith and Mr Michael Kelly respectively walk out with #95,300 and #66,500 — a victory for the Dempsey-McCann consortium, who have always insisted outgoing directors should not profit ”from failure”.Mr Dempsey, who intervened on Thursday night to pull Celtic back from the brink of receivership with an immediate pledge of #1m to the bank, emphasised that no overnight change in club fortunes will occur.

He said: ”We did not have the luxury to meander through issues that have caused concern at Celtic. The issue was to keep Celtic alive, and the answer was yes.”The new board’s immediate role was to demonstrate to fans that new opportunities and a new future exist.Mr McCann agreed; time was needed to analyse the position, and he admitted that no money for the playing side will be immediately available.However, he stressed the club’s financial predicament has been resolved: ”The club is now in safe hands and the financial position of the club is now secure.”Mr McCann — who described yesterday’s events as a ”complete and utter victory — confirmed his original #17.8m rescue package rejected by the old regime last year still stands.It would appear about #8m of his own money will be put into the club, with much of the rest raised via a restructuring including a shares issue aimed at supporters. The package will be put to a shareholders’ egm to be called soon.He will take over as club chief executive on Monday, and expects to move to Scotland soon afterwards.

Mr McCann said: ”My message to the fans is sympathy and appreciation.They have tolerated so much and put up with a terrible situation for so long. I would urge them to get behind the club again and morale will quickly rise.”

He said he was prepared to talk to millionaire businessman Gerald Weisfeld with a view to encouraging him to investing in the Parkhead club. Mr Weisfeld failed in a bid last month to oust five directors by offering them #300 a share.Mr Dempsey will not have a seat on the new board, despite launching his power struggle when ousted after six months in 1990.He claimed subsequent actions were not personally motivated, but based on a desire to restore Celtic’s fortunes.Surprisingly, Mr Dempsey did not rule out a move to Cambuslang; he said everything connected with the club is only subject of review.Asked whether the job of manager, Lou Macari, was on the line, Mr Dempsey said: ”That doesn’t come into question at this time.”

There was a delay over an official announcement of the new board as lawyers examined the small print of the coup.This was to ensure the transfer of power was watertight and could not be challenged at a later date by ousted directors.Mr Kevin Kelly remains as chairman, with directors Tom Grant, James Farrell, and Jack McGinn also staying on the board despite complaints from some Celtic fans that they should have known about the club’s declining fortunes.

Also co-opted on to the board will be former Edinburgh banker Dominic Keane, long associated with the rebel faction.The board has been reduced in size from seven to six. That may suggest a place is being held for Mr Weisfeld, the former owner of the What Everyone Wants chain.Mr Smith, who joined the board in February 1990, was appointed deputy chairman because of his business acumen and City contacts.However, not only did he preside over alarming losses, his ”visionary package” launched a week ago to relocate Celtic Park in Cambuslang and float the business was ridiculed by the media and, even worse, the club’s bank was not prepared to go along with it.Mr Smith, when he flew in from London where he works, had said he would not resign. But a spokesman for Mr Smith acknowledged defeat when he said: ”He has no more rabbits to pull out of the hat.”The official, who also speaks for Mr Patrick Nally, of StadiVarios, the company charged with raising finance for the Cambuslang project, said he was shocked by the turn of events that jeopardised the scheme, one of six in the UK involving Superstadia Ltd for sporting arenas.

Former Lord Provost Michael Kelly’s removal coincided with his Glasgow public relations firm losing one of its most important clients –Celtic.None of the ousted directors would comment yesterday, and they were still locked in talks with financial and legal advisers last night.Negotiations with the trio lasted all day after an emergency board meeting was called.Messrs Kelly, Grant, Farrell, and McGinn had been told the club was in ”immediate and dire peril” of being put into receivership. They were given 24 hours to pledge all their shares and proxies against the mounting overdraft, and sought an accommodation with the McCann-Dempsey consortium. It has already pledged #1m, with #5m to follow on Wednesday.The final straw for the bank was the revelation that only a conditional agreement, in principle, to provide guarantees of up to #20m towards construction costs of a #50m Cambuslang stadium was in place.The new regime is likely to remain at Parkhead, where money will be made available to make Celtic Park an all-seater stadium.Mr Smith’s grandiose plan to relocate Celtic collapsed after a spokesman for little known Geneva-based merchant banker, Gefinor, denied it had any involvement in the project.

Directors arrived at Celtic Park up to an hour early for the scheduled 10am board meeting.Shortly after 2pm, Celtic’s new saviour arrived. However, it is doubtful whether the slightly built Canadian-based tycoon expected quite such a welcome.His arrival sparked a frenzied response from the group of about 100 fans, who had been camped outside the stadium. They immediately broke into song.Despite the icy wind and rain, the numbers outside the stadium continued to swell.There was a further flurry of excitement just after 4pm when Mr McGinn left the stadium via a rear door and into a waiting car which sped off.His sudden departure aroused speculation that he, too, had been ousted but it was later revealed that his departure was due to UEFA commitments in Geneva.The growing unease among the fans was appeased an hour later when new director, Dominic Keane, came outside.Mr Keane delighted his captive audience by predicting a swift return to the glory days.

”I am absolutely confident that under Brian and Fergus Celtic can only go one way and that’s to the top.”It will all fall together and bring Celtic back to the great days, not only in Scotland but Europe.”The director remained optimistic that his financial acumen gleaned from more than 21 years in the banking world would prove invaluable in improving Celtic’s standing within the business community.Earlier Matt McGlone, who spearheaded the Celts for Change campaign, said that he was absolutely ecstatic by the day’s developments. In fact, he went as far as to say it was the best day in his life.He described the ousting of the three board members as a victory for every Celtic fan although he voiced regret that there was not a ”clean sweep”.

”There can be no respect for the board members who have remained.”The Celtic for Change campaign had booked the City Halls in Candleriggs, Glasgow, for a rally on Monday night with Mr Dempsey and Mr McCann invited to speak. This event, Mr McGlone said, would now become a victory rally.”Earlier, Celtic player Charlie Nicholas warned fans not to expect miracles overnight.Speaking after training, he said: ”There is no guarantee for immediate success. However there is certainly more hope with a man like Brian Dempsey heavily involved.”

When Fergus McCann met Celtic’s youngest shareholder

11 March 2011 (source: STV.tv)

Following his takeover of the club in 1994, one encounter with a supporter made Fergus McCann realise the importance of Celtic.

Fergus McCann has said that he came to realise what Celtic means to the club’s support after meeting one fan while shopping in Glasgow. The former Celtic owner was sharing his memories of 1994 with The Football Years, which is broadcast on Friday, March 11 at 9pm.

Scots-Canadian businessman McCann took control of the Parkhead club when it was just hours from bankruptcy, purchasing a 51% stake in Celtic. He oversaw a move to financial stability, in addition to the rebuilding of the club’s stadium, but says the emotional importance of the task really hit home after an episode in the city.

“Not long after [taking control], a few months later, I was out shopping on a Saturday morning in Glasgow,” McCann explained.

“A man was carrying this baby and he raised him up and said ‘Fergus! Celtic’s youngest shareholder’.

“When you think about it, that’s quite daunting. It’s a huge, huge part of people’s lives. It’s part of people’s identity.

“It’s very important and you can’t underestimate that.”

McCann left the club in 1999, having insisted from the moment of takeover that he would only hold his majority of shares for five years. The businessman put in place steps to encourage and allow individuals, primarily ordinary fans, to have a greater stake in the ownership of the club, a move that may well have been inspired by his meeting with one very young Hoops fan.

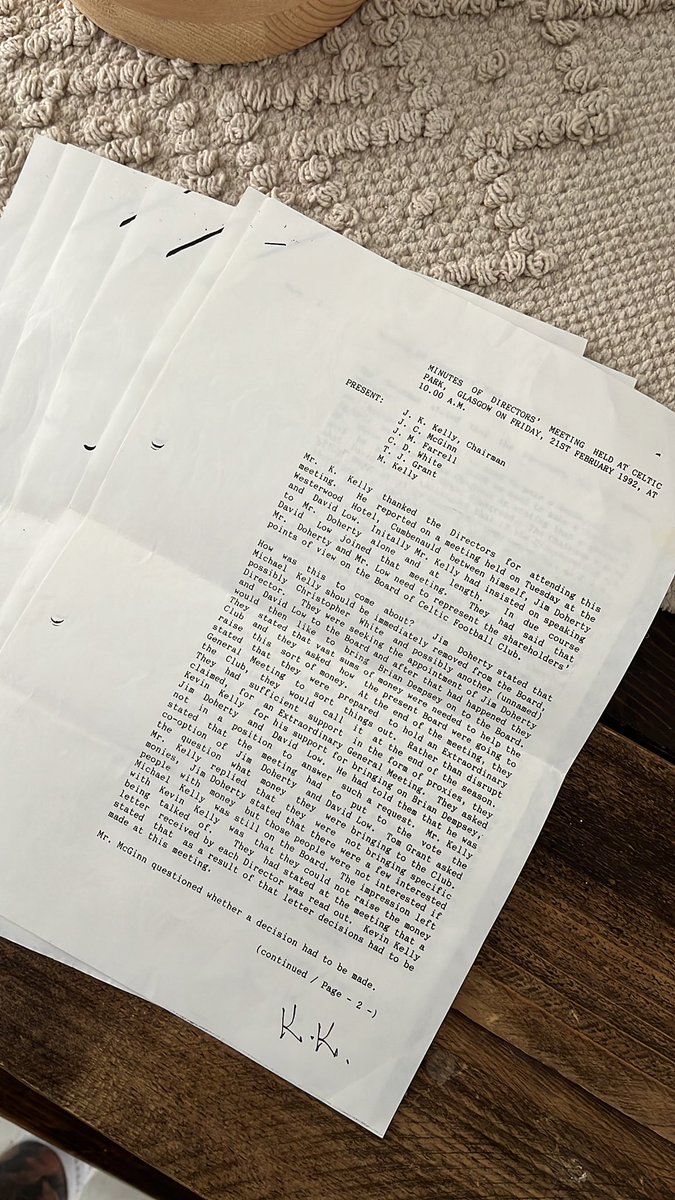

Fergus McCann’s battle to save Celtic from bankruptcy detailed in unseen board documents

http://www.dailyrecord.co.uk/sport/football/football-news/fergus-mccanns-battle-save-celtic-3013568

Jan 2014

TWO decades ago an unlikely saviour walked through the gates of Celtic Park after the club had lurched towards disaster. Armed with new interviews and unprecedented access to boardroom documents, club director and historian BRIAN WILSON remembers how Fergus McCann saved Celtic.

TWENTY years ago, Celtic faced the biggest crisis in their history with the threat of bankruptcy staring the club in the face.

During the early months of 1994, they edged even closer to the brink before being rescued with minutes to spare through the intervention of Fergus McCann.

For decades, the board’s priority had been to break even and avoid debt. There were no cash reserves and the only source of finance was a rapidly mounting Bank of Scotland overdraft.

In writing the Official History of Celtic to mark the club’s 125th anniversary, I had access to records and correspondence which throw light on these crisis years and key moments within them.

I also visited McCann at his office in one of Boston’s less glamorous suburbs from which he now runs his charitable foundation.

Now, as back then, he does not believe in spending money on the trappings of wealth or status.

He showed me the letter from the Bank of Scotland’s general manager which gave Celtic less than 24 hours to continue in the first days of March 1994.

The records also show how the old board underestimated McCann, turning him from potential ally into enemy.

Since the unexpected League and Cup double which capped Celtic’s centenary season in 1987-88, the club’s record had been woeful.

Increasingly, the supporters directed their frustration at the board which, for almost a century, had been dominated by two families – the Kellys and the Whites.

Celtic were still a privately owned company with a share capital of £20,000 – a structure hopelessly unsuited to the pressures they now faced.

These included a requirement to create an all-seater stadium within four years in response to the Taylor Report on ground safety.

The board continued to look for ways of addressing these problems without giving up control of the club. They regarded their role as a form of trusteeship – a belief with which most supporters had lost patience.

McCann’s first approach to the board was early in 1989. According to board minutes, he wanted to “provide finance for various capital expenditures linked with equity purchase (and) giving him a very high-profile position within the Club”.

The board – then consisting of Jack McGinn, Chris White, Kevin Kelly, Jimmy Farrell and Tom Grant – unanimously turned him down. When McCann responded with fresh proposals, the same view was taken and the board told him they “hoped this was a final discussion on the subject”.

McCann recalled: “My initial intention was to support a competent board with some capital and marketing activity. There was none of either.

“The main emotion I found myself dealing with was fear of change, of something bad happening. That was throughout the families.”

McCann’s involvement with others seeking change was mainly a marriage of convenience– not least because he was totally opposed to leaving Celtic Park.

He told me: “I had never doubted that the answer was to redevelop it into a 60,000-seater stadium.

“I measured the distance from the cemetery to the touchline – 42 yards – in order to work out how the stand to replace The Jungle could be built and how many it would hold.”

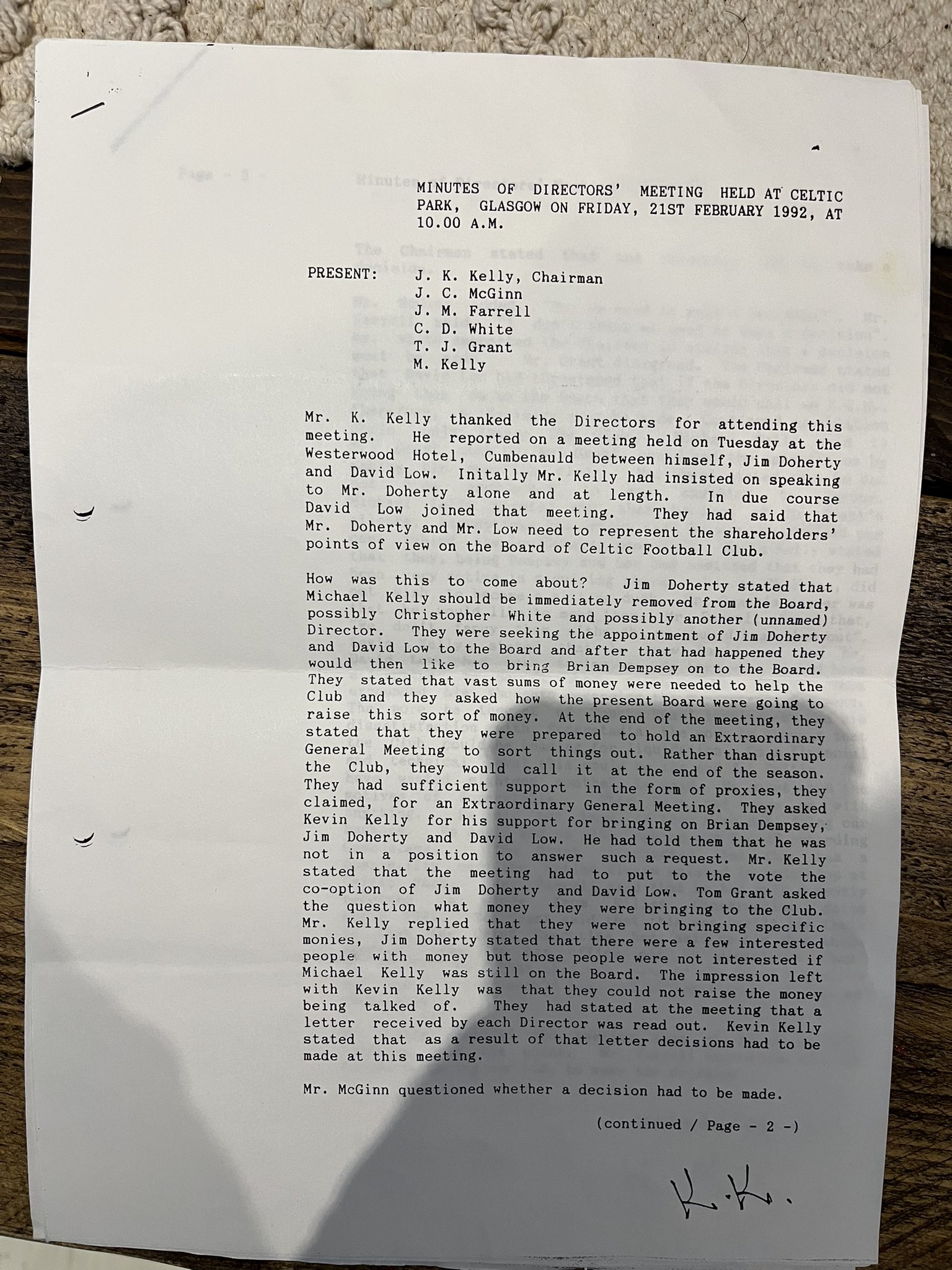

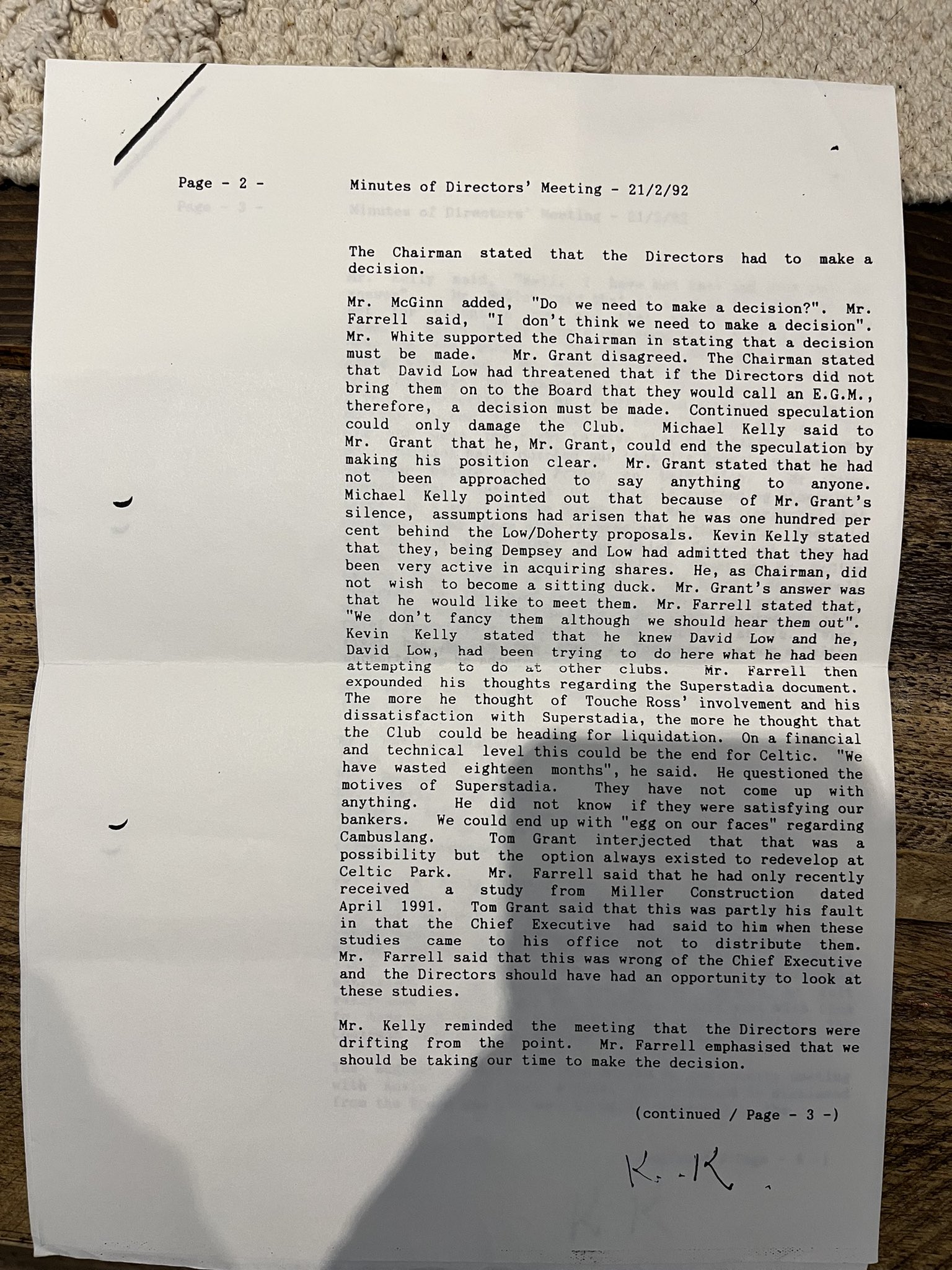

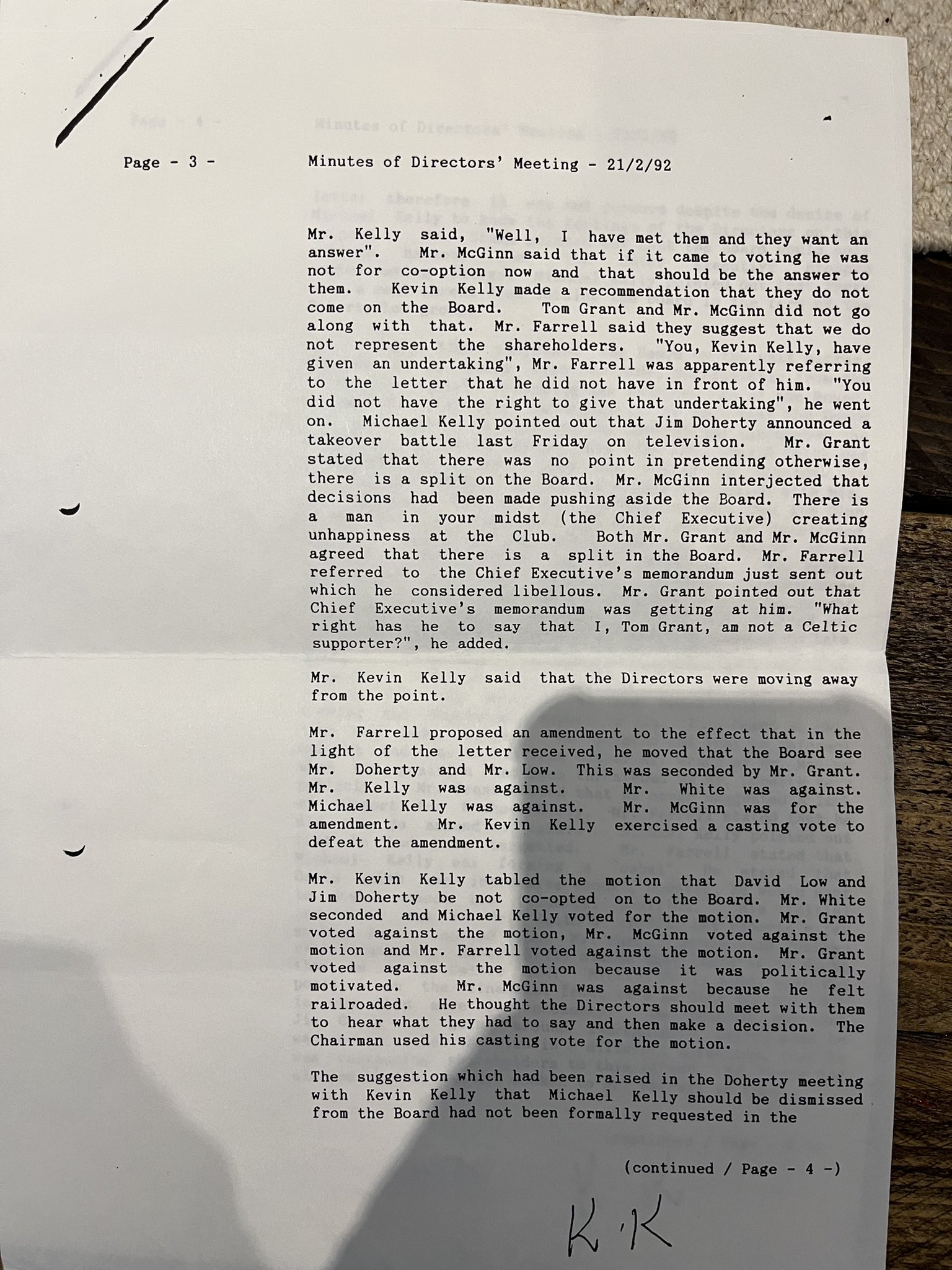

By May 1992, the Celtic board realised that McCann could be their saviour rather than a threat. A board meeting heard that Michael Kelly had tried to contact him, without success.

The board were told: “He understood that Mr McCann just wanted to go away.” This proved to be a serious misreading of the Canadian tycoon’s intentions which were to replace the existing board rather than work with them.

Ultimately, it was neither supporters nor shareholders who brought matters to a head but Roland Mitchell, general manager of the Bank of Scotland in Glasgow.

The brief managerial tenure of Liam Brady had been disastrous and spending on players had taken Celtic to the limits of their £5million overdraft.

Mitchell decided to call time and, if necessary, force the historic club to the wall.

On February 25, 1994, an increasingly desperate Celtic board announced plans for Celtic PLC, promising “a glittering new future in the 21st century” based on a move to Cambuslang.

It was too little, too late.

On March 3, Mitchell told club chairman Kevin Kelly that cheques would only continue to be honoured if “by 12 noon tomorrow a cash collateralised or otherwise acceptably supported guarantee for the sum of £1million is put in place to support the bank’s overdraft”.

The other condition was that McCann “superseded” this with “a £5million cash collateralised guarantee” the following week. McCann flew in from Canada to meet that

challenge.

But he remains bitter about his treatment by BoS who, he believes, did not wish him to succeed in buying the club.

He recalls: “I had taken them completely off the hook. They were never going to collect the £5.2million they were owed otherwise. Ten months later, after the bank had been fully paid off, Charles Barnett, Celtic’s interim financial director, went to BoS to learn what they could offer in loan finance.

“Their proposal was £2.5million fully secured – little more than an insult.

“Later, we obtained £10million unsecured from the Co-op Bank in Manchester.

“What I resented enormously was trying to do a business deal in Scotland and being treated that way.”

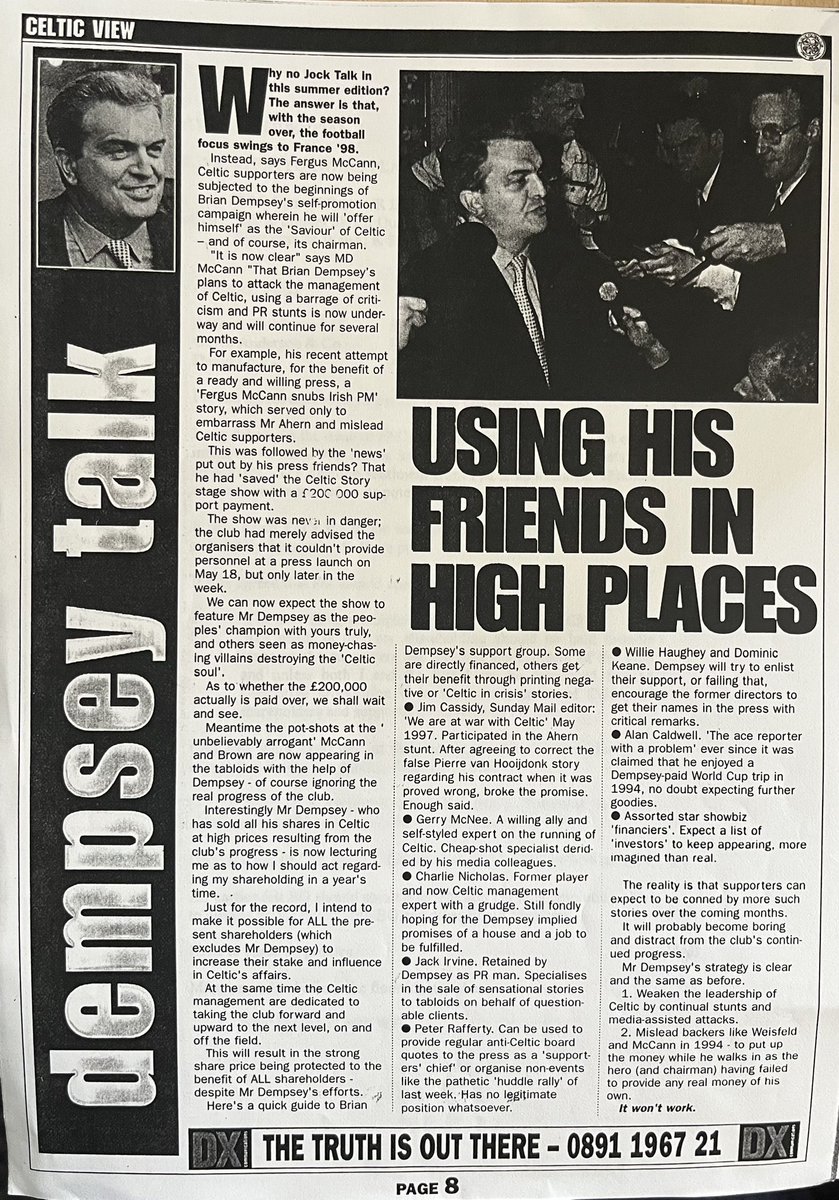

While McCann secured control in alliance with the widespread movement against the old board, none of its other leading figures ended up on the PLC board which emerged the following year.

Instead he built a small team around him, including City heavyweights Dermot Desmond, Sir Patrick Sheehy and Brian Quinn.

McCann’s greatest legacy was redevelopment of Celtic Park. At the time, attendances had slumped to 12,000 and the prospect of European success seemed remote.

He explained: “The season ticket concept was foreign to the club but it was the key to delivering big gates. It was a progressive decision to match reconstruction to the growth in ticket sales.”

McCann knew the season ticket principle from ice hockey in Canada where “if you didn’t have a season ticket, you didn’t get in”.

When he took over at Celtic, there were 7000 season ticket holders and when he left, there were 53,000. The rest, as they say, is history.

Boardroom minutes reveal just how close Celtic came to agreeing a move to Robroyston – and how Chris White, then company secretary, thwarted that potentially disastrous decision.

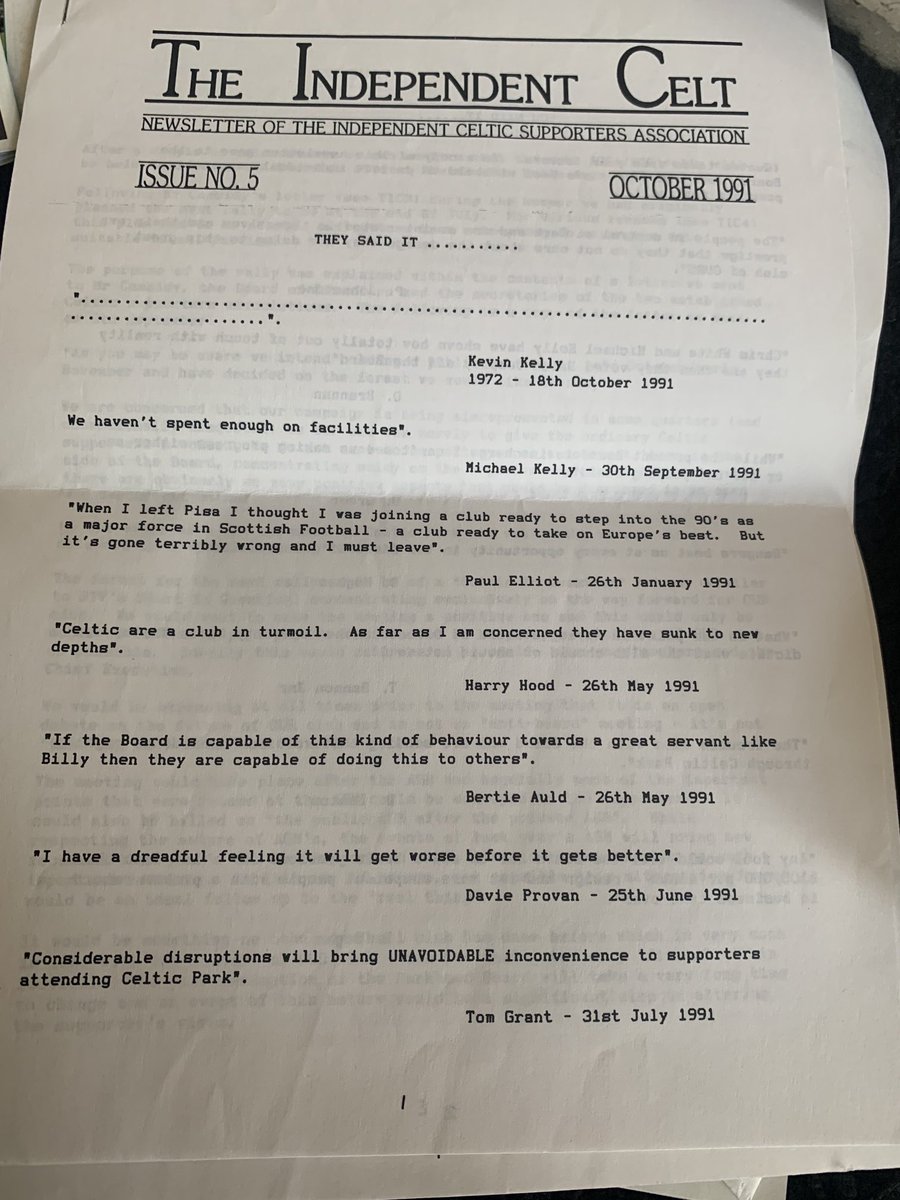

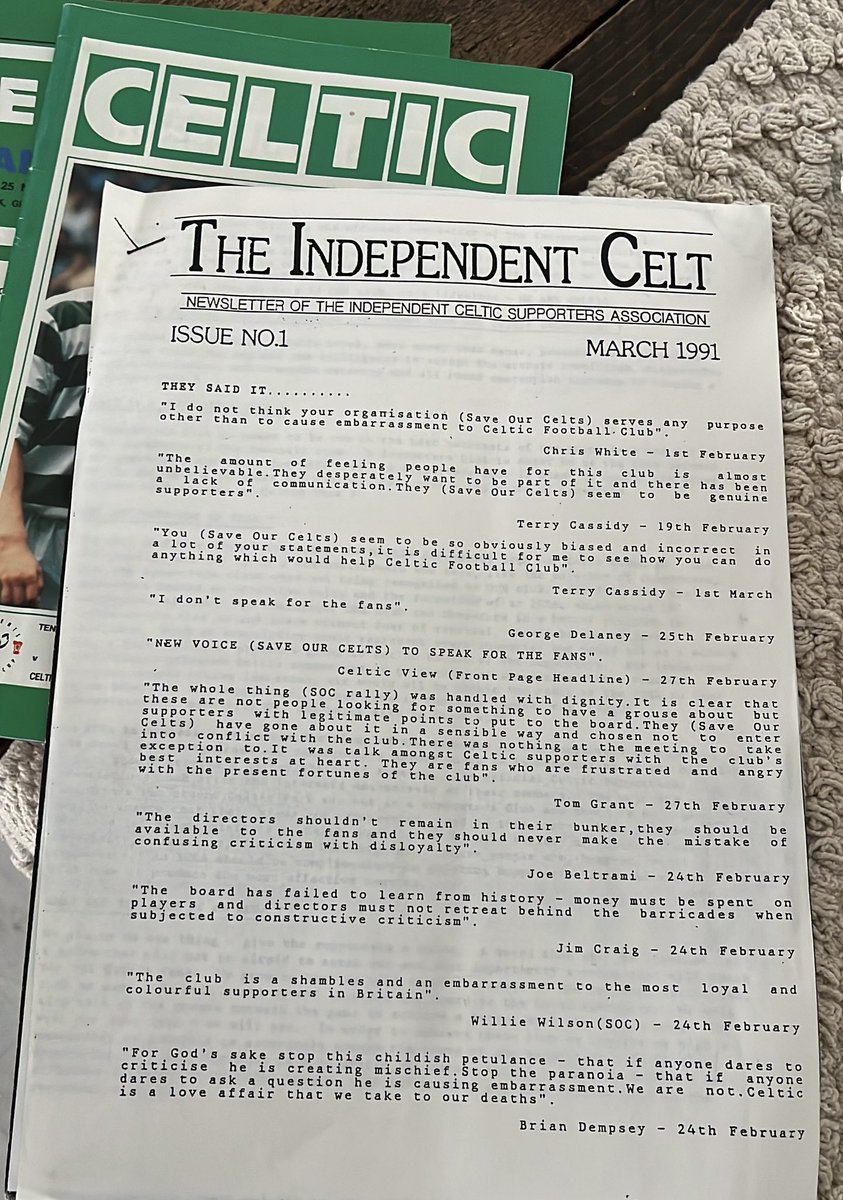

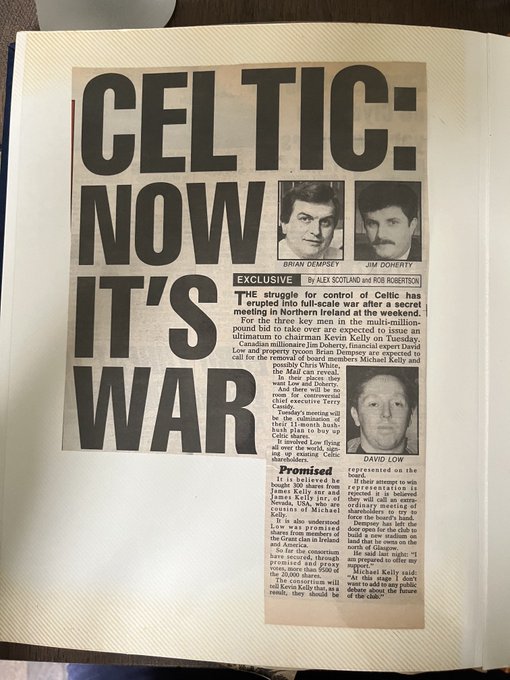

In May 1990, the board brought in property developer Brian Dempsey – a prominent Celtic fan.

White insisted that Dr Michael Kelly, former Lord Provost of Glasgow, should also be recruited.

A few weeks earlier, White had shown the board draft plans for redeveloping Celtic Park based on “twice as big an investment as any made by Rangers”.

The board, he said, needed “expert guidance in considering such a momentous decision”.

But an alternative plan emerged and, by late June, White was fighting a rearguard action against a drive to agree an entirely different project at Roybroyston.

The minutes recorded: “Directors discussed their preferences as regards existing stadia. Italian stadia incorporating running tracks were considered lacking in atmosphere while the Parc des Princes in Paris was considered by most to be an ideal arena for football.”

An organisation which had no money and was lurching from one crisis to the next was seriously contemplating construction of the Parc des Princes in Robroyston.

Chris White warned against the move, which was being backed by Dempsey.

He told the board: “The club is committing itself to a minority interest in a partnership with another developer.”

By the time of Celtic’s AGM in October, White and Kelly had decided to vote Dempsey off the board, less than six months after he joined.

Dempsey went on to become the focal point for a campaign for change at the club.

How many within it would have shared his enthusiasm for a move to Robroyston is more doubtful.

Sunday Mail Feb 1994

McCann revives interest in Celtic

The Scotsman 31/01/1994

By Hugh Keevins

THE five-man consortium headed by the multi-millionaire, Fergus McCann, who tried to take over Celtic last month are ready to try again. The group considers the Scottish Cup defeat at Motherwell to have serious financial implications and will now wait to see if the end of the season finds the Celtic board left with no option but to concede they can no longer carry on.

Celtic have had no revenue since they played Aberdeen on 18 January and are not due to play at home again until 26 February against Kilmarnock. The club’s wage bill and operating expenses are thought to come to 140,000 per week and the cost of servicing their overdraft is a further 8,000. Celtic’s debt therefore will have risen by more than half a million pounds before they earn a penny through the gate.

There are only seven home matches left to be played before the end of the season and none of them could be described as meaningful. There is no Scottish Cup or European matches to provide financial comfort, either. Even the final Old Firm game of the season is to be staged at Ibrox with Rangers as the sole beneficiaries.

Talks involving McCann and the other members of the consortium took place at the weekend and it is understood the Montreal-based McCann believes that it has to be now or never where his bid for control of the club is concerned. McCann’s fear is that many more months of operating at a severe loss will make Celtic too much of a financial risk. when creditors have to be taken care of, along with the bank, and both the team and the ground need considerable sums of money spent on them. In what is a cash flow business, the Scottish Cup result is likely to have the effect of further reducing already declining attendances. In spite of speculation that a Glasgow-based group were also willing to buy out the shareholding of individual members of the Celtic board, nothing has happened. McCann’s proposition would not result in personal gain for any director but would provide the funds to re-capitalise the club. McCann has told his fellow investors that he will not become involved in a Dutch auction for the club. A proposed meeting of the consortium in the Cayman Islands earlier this month did not take place but a gathering is expected soon. as Celtic go into that period between now and the end of the season that will make or break the club.

Lou Macari, Celtic’s manager, repeated his request for money to improve the team before he left Fir Park on Saturday night but at a time when the manager has been forced to put down 75,000 for a goalkeeper, Carl Muggleton, and pay the rest of his 150,000 fee on an instalment basis his prospects of receiving a windfall do not look good. “When we’re at our best, we’re good enough but being just good enough is not good enough for Celtic,” he said. The manager’s view is shared as far afield as North America, from where developments are being watched with interest.

Celtic hit by one-two from protesting fans

The Scotsman 02/03/1994

By Susan Dean

UP TO 300 Celtic fans walked out during last night’s game with Kilmarnock – the worst attended match at Parkhead in six years – in protest at the Celtic board. The walkout had been organised by groups of supporters in conjunction with a boycott of the match. Their plan seemed to have been effective because the Parkhead crowd was 10,882, which included about 2,000 Kilmarnock supporters. The walkout, in the 60th minute of the match, was jeered by the Celtic fans who stayed. The boycotting supporters claimed not to be disappointed at the number who had left the stadium, saying that the crowd size showed the dissatisfaction with the board.

Malcolm Jones and Paul Drysdale, from Alloa, who walked out, said it had been the only way to show their feelings. ”We are season-ticket holders and this was our way of putting our point over because we’ve already paid to attend the match,” Mr Jones said. Another fan, Michael Fisher, from Motherwell, said he had walked out but was not bothered that most of the crowd did not follow suit. ”It is up to the individual to do what he or she wants. The only thing that will put this board out is the Bank of Scotland.”

The walkout and boycott ended a day in which Celtic was plunged into another crisis over allegations about the funding for the proposed stadium at Cambuslang. A newspaper claimed that Gefinor, a Geneva merchant bank which Celtic said was providing the 20 million needed to revive the club, has denied that a deal had been struck. Frantic attempts were made yesterday by a Celtic director, Michael Kelly, to clarify the status of the promised money.

Last Friday Celtic’s vice-chairman, David Smith, said that Gefinor had underwritten the initial 20 million. The club, he said, would raise up to 6 million to reduce its overdraft of about 7 million and buy players by issuing about 25,000 shares.

The latest allegations prompted renewed calls for the Celtic board to step down. Brian Dempsey, the Glasgow businessman involved with a consortium which wants to put 18 million into the club in return for the board’s resignation, called on Mr Smith to give the fullest possible public statement. If the allegations were true, he said it was a ”disturbing” way to do business. Peter Rafferty, the chairman of the Affiliation of Celtic Supporters, said the news was the ”final straw” and put the club into disrepute. ”The board should go lock, stock and barrel, particularly David Smith, who gave 100 per cent assurances that this was OK,” he said.

Mr Kelly was said last night to be waiting to ”make contact with the people necessary to obtain answers to questions about Gefinor”. Mr Kelly issued a statement which read: ”We have no reason to believe that anything has changed since Friday.” Mr Smith was not available for comment.

________________________________________

Empty gesture: Wide open spaces were not confined to the pitch as Celtic played in front of their lowest home gate in six years. Picture: David Mitchell

Collins strikes late to outfox Kilmarnock

The Scotsman 02/03/1994

By Roddy Thomson Celtic1 Kilmarnock 0

A CROWD of 10,882 watched a last-minute free kick from John Collins keep alive Celtic’s one remaining realistic aim, a place in Europe, is still within their reach. A Bobby Williamson foul on Celtic’s stand-in captain (Paul McStay was a surprise absentee), gave Collins his fifth goal this season from a drive which took a wicked deflection off the defensive wall.

Throughout most of the preceding 89 minutes, Celtic had looked a forlorn outfit, and it is left now to Kilmarnock to rue a point cruelly lost as they slip ever closer into the relegation mire.

The Celtic board may be considered inept by all and sundry, but they have shown no little skill in keeping predators at bay. They were outsmarted just before half-time, however, when a fox came on to the park and ran the length of the pitch. Wild days indeed.

The only near-thing in a poor first half was a 19th-minute Gus McPherson volley for Kilmarnock which cracked back off a post. Macari had started in 3-5-2 formation, but his plan was forcibly altered when Paul Byrne had to replace the injured Gary Gillespie. Damage to players, in fact, was the main theme during this period with Kilmarnock’s Mark Reilly stretchered off moments earlier after a clash of heads with Brian O’Neil.

With the action as appetising as your average rodent’s dinner, chants of ”sack the board” from those who had resisted the boycott calls finally broke out. A tame Willie Falconer header was all Celtic had in reserve before the break. Collins began to suggest that he might have an important say in the final reckoning when a 49th-minute swirling volley was deflected past Ray Montgomerie. But hopes of an improvement in the general play were ill-founded.

Ally Mitchell again left Tony Mowbray for dead – the latter foolishly attempting an overhead clearance.

If the fear factor is killing the ability of teams such as Kilmarnock to take a leading role in mid-table affairs, who can lift Celtic out of their present mode? As free kicks were conceded instead of throw-ins, so poor clearances badly utilised were simply repeated – Craig Napier’s carefree 18-yard volley being followed by a Brown shot plucked all too easily out of the air by Carl Muggleton.

This was effectively Celtic’s only home match in eight weeks and it seems preposterous now to even contemplate a club revival emanating from the pitch.

Attendance: 10.822

Celtic: Muggleton, Gillespie, Boyd, Martin, Mowbray, McNally, McGinlay, O’Neil, Nicholas, Falconer, Collins. Subs: Byrne, Vata, Bonner.

Kilmarnock: Geddes, McPherson, Black, Montgomerie, Brown, Millen, Mitchell, Reilly, Williamson, Burns, Napier. Subs: McCluskey, McInally, Mathews.

Referee: W Crombie (Edinburgh).

Financier says Celtic row may put bankers off

The Scotsman 03/03/1994

By Gordon Milne

PATRICK NALLY, the man at the heart of the Celtic board’s attempt to move the club to Cambuslang, last night gave warning that its Swiss backers could be reconsidering their involvement.

”Put it this way – if I was Gefinor, I would certainly be having second thoughts,” he said. Mr Nally, managing director of Stadivarious, which is putting together the funding for troubled Celtic’s controversial proposal to move to Cambuslang, said last week that Gefinor was behind a 20 million finance package.

On Tuesday, Gefinor denied that any agreement had been concluded, plunging the Celtic board and fans into yet more confusion.

Last night Mr Nally said Gefinor were only ever providing bridging finance for the stadium construction and there was no formal link with Celtic. Yesterday the Geneva-based merchant bank was said by Mr Nally to be ”absolutely shocked sideways” by the hostile reaction to the Celtic board’s plans.

”I don’t know what their view is – at this present moment I’m obviously waiting – but my own instinct would tell me that they’d be very concerned. Why enter the arena when there’s all this emotion and venom and backbiting and conspiracy? It seems a very silly thing to want to do.”

He said that there was no reason for Gefinor to have a contractual relationship with Celtic. Its interest was entirely towards construction finance.

Mr Nally defended his decision to name Gefinor at last Friday’s news conference announcing the board’s plans to float the club on the stock exchange. He said he had been under pressure to be more open about the funding package in an attempt to garner support.

”In many respects I think it was a naive decision to try and be open. Maybe it would have been better to say nothing and carry on in the same old clandestine way.”

Mr Nally said the Gefinor role was no more than bridging finance, and that ultimately the commercial rights of Cambuslang would be sold on to commercial sponsors.

”But you can imagine what would happen if we were talking to high-profile sponsors in this environment. The machinations of the media would absolutely terrify them. No company would subject themselves to that.”

Asked how it would all be resolved, Mr Nally replied: ”Have you got your crystal ball there?”

Celtic stadium confusion

The Scotsman 03/03/1994

By Alan Dron and Iain Duff

CONFUSION continued to surround the finances for Celtic FC’s planned stadium at Cambuslang last night, 24 hours after reports that the merchant bank said to be backing the scheme had denied all knowledge of it. A spokesman for Stadivarious, the Oxford company arranging finance for the 50 million project, cast doubt on the accuracy of newspaper reports which gave the story its latest twist, saying the deal was still on.

The merchant bank Gefinor, of Geneva, could not be contacted.

Celtic also planned to comment on the affair yesterday. As the day wore on, however, a spokesman first said that the club’s statement would be delayed, then that it would not be issued until today. Club sources insisted that the money was in place with Stadivarious, subject to conditions.

Yesterday’s developments followed a newspaper report that Gefinor, said last week to be providing the cornerstone 20 million for the project, had denied all knowledge of the deal. Celtic sources said that one possible area for confusion was that Gefinor had never had any direct contact with the club, but only with Stadivarious. That would explain the comment by a Gefinor executive committee member, Edward Armaly, that he had had no dealings with Parkhead. Mr Armaly was in talks with Patrick Nally, of Stadivarious, in New York on Tuesday. Late yesterday, a spokesman for Stadivarious said that the talks had been ”only one of a whole series of meetings” between the two organisations and had not been triggered by the reports of the lack of finance. There had been ”nothing dramatic” about the meeting. ”As far as I’m concerned, nothing has changed from what [Celtic vice-chairman] David Smith said on Friday.”

The spokesman was asked how he explained the extensive quoted remarks in an evening newspaper from Mr Armaly. In those the latter said he had not proceeded with an agreement with Stadivarious on funding for Celtic’s stadium in spite of initial contacts some months ago. The spokesman said: ”I can’t speak for Gefinor, but … I have a question mark over the accuracy of those quotes.

”It requires an understanding of the mechanics of the transaction, which were explained last Friday. It’s very easy, I suspect, to take the mechanics of that transaction out of context, and that, I suspect, is what the Evening Times has done.”

It was quite accurate and hardly surprising for Mr Armaly to say he had had no dealings with Celtic. All the banker’s negotiations had been with Stadivarious, not the club, he added.

A Gefinor spokesman in Switzerland was reported last night to have repeated that no funding for Cambuslang was in place. David Smith, Celtic’s deputy chairman and the driving force behind the Cambuslang plan, was not at the club or his London offices yesterday.

The turmoil in the Celtic boardroom dates back to 1990. Steps were taken then to remove Brian Dempsey from the board after his proposals to move Celtic to Robroyston in Glasgow. The split has never closed. There has been increasing acrimony as board proposals to build a stadium at Cambuslang have hit snags and the club’s financial position has deteriorated. Mr Dempsey was voted off the board after six months.

Eighteen months later, in March 1992, he was backing a plan by a Scottish-Canadian businessman, Fergus McCann, to buy a say in the running of the club. Details of that were revealed by Mr McCann in March 1992 on the eve of an extraordinary general meeting. It was called to try to remove the directors James Farrell and Tom Grant from the board. They were considered too outspoken by colleagues. In a letter to shareholders, Mr Farrell criticised the Cambuslang proposal. It could ”lead to the possible liquidation of Celtic”. Mr Farrell and Mr Grant kept their seats on the board but a new appointment was ratified, David Smith as vice-chairman.

In May 1993, Glasgow District Council granted outline planning permission for the 50 million stadium at Cambuslang.

Mr McCann arrived in Scotland to attend the club’s annual meeting in October and call for an extraordinary meeting to push his plan through. At the annual meeting, after an unsuccessful attempt to prevent Mr McCann from speaking or voting, the directors agreed to meet him to decide what was best for the club. It was revealed that five directors had signed a pact, Celtic Nominees, agreeing not to act independently of each other: they are Michael Kelly, Kevin Kelly, David Smith, Tom Grant and Christopher White.

The 24 hours before the annual meeting saw the resignation of the club’s manager, Liam Brady, followed by the resignation of his assistant, Joe Jordan.

In November, Mr McCann withdrew his plan after he failed in a Court of Session move to disfranchise the five directors who had signed the pact.

In January, the new Celtic manager, Lou Macari, set up a meeting between angry supporters and the directors to try to restore support for the team.

At the end of the month, another group, backed by Gerald Weisfeld, made its move on the club. Its bid was rejected.

Last Friday, the Celtic board made the triumphant announcement that 20 million was in place to move to Cambuslang … followed by bank denials that they knew anything about the deal. And the fans got a new board and the board got a new stadium and everyone lived happily ever after …

Fergus McCann seizes control of Celtic

The Scotsman 04/03/1994

By Hugh Keevins

THE expatriate millionaire Fergus McCann and the former director Brian Dempsey are to take control of Celtic FC, which was dragged back from the brink of receivership last night.

Two board members are being asked to resign. Celtic said that the club had been saved from receivership only after the chairman, Kevin Kelly, and Mr Dempsey had given undertakings to its bank, the Bank of Scotland.

A board meeting today will invite Mr Dempsey and Mr McCann to take charge of the club. The announcements followed a meeting between four club directors and the bank.

Celtic said the board was seeking the resignation of the club’s director/secretary, Christopher White, and David Smith, the vice-chairman. It said that the four directors at the meeting had been told the club was in immediate danger of being put into receivership and the extent of its financial difficulties had been kept from the full board. The directors at the meeting were Mr Kelly, Tom Grant, James Farrell and Jack McGinn.

Full report, Page 30

McCann, a multi-millionaire, had, with Dempsey and three others, deposited 13.8 million in the Bank of Scotland last year as part of an attempt to wrest control of the club from the seven-man board of directors.

No HeadlineThe Scotsman 04/03/1994

By Hugh Keevins FOOTBALL CORRESPONDENT

Celtic Football Club was last night saved from receivership by the intervention of the director who was removed from the board four years ago, Brian Dempsey.

A board meeting to be held this morning will invite Dempsey and the expatriate Scot, Fergus McCann, to take control of the club with the full agreement of the Bank of Scotland.

Yesterday four directors of the club, Kevin Kelly, Tom Grant, James Farrell and Jack McGinn, met with the Bank of Scotland, the club’s main lender and mortgage holder. Last night it was decided to seek the resignation of the club’s director/secretary, Christopher White, and David Smith, Celtic’s vice-chairman. Smith and White have been accused of withholding from the board the full extent of Celtic’s financial plight. The club’s bankers told the four directors present that Celtic had been in ”immediate and dire peril” of being put into receivership.

The intervention of Dempsey has eased the club’s position in the short term. The only mystery which remains to be solved is the immediate future of another Celtic director, Michael Kelly. The man responsible for the club’s public relations was not present at last night’s meeting with the bank but neither has his resignation been sought.

Last night Celtic’s chairman, Kevin Kelly, said: ”I am delighted with what has been achieved in securing the continued existence of Celtic Football Club and I look forward to determining the way ahead for the club with Brian Dempsey and Fergus McCann.

”The bank are also delighted with this solution which enables us to pursue the future we all wish for this club”.

McCann, a multi-millionaire, had, along with Dempsey and three others, deposited a total of 13.8 million in the Bank of Scotland last year as part of an attempt to wrest control of the club from the seven-man board of directors. At an extraordinary general meeting held last November, however, his proposal was defeated and he returned to Montreal saying he would only intervene in Celtic’s affairs once again if it were at the invitation of the bank. McCann is expected to arrive in Glasgow today and be reunited with Dempsey, the man who was a Celtic director for six months before being removed at an annual general meeting. Since what Dempsey believes was a dismissal choreographed by Christopher White and Michael Kelly, he has vigorously pursued control of the club and now seems to be on the verge of achieving his aim. Celtic’s debts are believed to total in excess of 6 million and their ground and team both need considerable sums of money spent of them as well.

Saviour’ stripped of his powers

The Scotsman 04/03/1994

By Hugh Keevins and Audrey Gillan

DAVID SMITH, the man who was brought on to Celtic’s board two years ago to transform the financial fortunes of the ailing club, was last night stripped of his executive powers.

The action was taken by the four directors – Kevin Kelly, Tom Grant, James Farrell and Jack McGinn – who were made aware by the bank of the club being ”in peril” of receivership. Smith stands discredited along with those directors who have been responsible for turning an accumulated profit of 169,000 in 1987 into a loss of unspecified size in 1994.

Celtic’s exact indebtedness can only be guessed at but all the indications last night were that the Bank of Scotland had informed the directors, who had earlier been called to a crisis meeting, of staggering figures. The legally binding voting pact, Celtic Nominees Ltd, of which Smith, Michael Kelly, Christopher White, Tom Grant and Kevin Kelly had been signatories, is now in tatters.

Last Friday it had seemed that the board was on the verge of disbandment in the face of various offers for the club. Smith, though, caught everyone on the hop by issuing a three-pronged statement on the club’s future. At a hastily convened press conference he said that Celtic’s move to Cambuslang was a ”reality” and that the club would be calling for an extraordinary general meeting at which they would seek approval for the issue of 25,000 new shares. The sum raised, approximately 5million, was to be used to reduce the club’s borrowings.

The move to Cambuslang was to have been the forerunner of a move to transform Celtic into a public limited company, creating one board to look after the affairs of the club and another to administer the new complex which was to include a 10,000-seater indoor arena catering for basketball and ice hockey.

As late as yesterday evening, Michael Kelly was still insisting that this scheme had the backing of a merchant bank, Gefinor, in spite of denials from it that any funding had been promised. Kelly maintained that only the naming of the construction company involved in the building of the complex was necessary for the release of 20million of backing.

Smith, who has been told that he cannot communicate with any bank employee on the club’s figures, joined the board in 1992 on the casting vote of chairman Kevin Kelly. Hailed as a saviour, the vice-chairman’s football plans may have come to grief but his track record in the business world speaks for itself. He was the Scot who led Isoceles in its audacious hostile 2billion takeover of Gateway supermarkets in 1989. Smith, from Brechin, trained as an accountant with Arthur Young in Glasgow and spent a time working on the liquidation of Upper Clyde Shipbuilders. After an involvement with Apple at the time the Beatles were breaking up, he moved into management consultancy. In February 1992 he was invited to join the board by Michael Kelly and White. He was not a member of the controlling families, but an answer to the demand that a financial and business heavyweight be brought in to oversee the control of the club. He was the architect of the Celtic Nominees pact which was signed by five of the board members agreeing not to act independently of each other and able to see of Brian Dempsey and Fergus McCann’s last bid to take over the club in November 1993.

But for Smith and Christopher White, that piece of paper is now in tatters. Smith last week celebrated, if that is the right word, his second anniversary as a Celtic board member. His status now is in question along with Michael Kelly and White. The three had once been offered £300 for each of their shares by Glasgow businessman Willie Haughey who had sought to take control of the club. Today, the value of their shares is open to conjecture as the final battle for Celtic gets under way.

New era at Celtic – once three quit

The Scotsman 04/03/1994

By Hugh Keevins FOOTBALL CORRESPONDENT

THE most dramatic board meeting in Celtic’s 106-year history is today poised to take the club into a new era under the leadership of rebels Fergus McCann and Brian Dempsey.

The sensational developments in the long-running Celtic saga which yesterday saw Dempsey and McCann give a 1million guarantee to the Bank of Scotland to prevent the club falling into receivership will almost certainly end the long-running battle for control at Celtic Park. McCann, the expatriate Scot, and Dempsey have pledged 5million to recapitalise the club but that offer is contingent upon three directors – David Smith, Christopher White and Michael Kelly – agreeing to resign from the board of directors by Wednesday. The first two have been charged by their fellow board members of failing to make clear the full extent of Celtic’s financial plight.

It now remains to be seen whether the trio choose to accept that ultimatum or attempt to enter into an arrangement with Gerald Weisfeld, the businessman who last week thought he had gained control of Celtic, only to be thwarted by the sudden announce- ment of plans to move the club to Cambuslang, issue 25,000 new shares and transform Celtic into a public limited company.

It is understood that White and Smith, along with Michael Kelly, were yesterday pursuing the possibility of doing a deal with Weisfeld.

Last night, Dempsey, who has waged a four-year battle for control of Celtic since he was removed from the board, said:

”The club was at death’s door. What we did by putting up our financial package was not out of personal gain; it was for the heart and soul of Celtic football club.’

The other choice before the three directors who can now be seen to have come apart from their fellow board members is to take the issue to an extraordinary general meeting and let the club’s shareholders decide who is best equipped to run the club.

The Bank of Scotland, Celtic’s main lender and mortgage holder, appears to have lost faith in those who once held the reins of power at the club and will back the group who yesterday provided a rescue package to prevent foreclosure. The 1milion guarantee last night offered by McCann and Dempsey will be posted by noon today but the board meeting that will be held first thing today can only be a stormy affair as families become divided in battle.

Kevin Kelly, Celtic’s chairman, says he looks forward to planning the future of the club in association with McCann and Dempsey. Kelly’s cousin, Michael, another part of the family synonomous with Celtic since the club’s formation in 1888, will do all in his power to ensure that is not the case.

Last night, McCann was on a flight to Scotland from Arizona. He and Dempsey will today front a press conference at Celtic Park if the three directors who are under fire capitulate in the face of overwhelming opposition and change the face of a club where three families, the Kellys, Whites and Grants, have held sway for over a century. Should power change hands, Dempsey says he does not want to be a member of the new board of directors.

”It is time for a healing process to begin. Fergus can be the technocrat who is the club’s figurehead. I want only what is best for the club.”

The installation of a new board would effectively dismantle the notorious voting pact entered into by five directors and put an end to the proposed move to Cambuslang on the outskirts of Glasgow. McCann and Dempsey have always stated their opposition to the idea of moving the club from its traditional base. The same resistance is unlikely to be applicable to any other sphere of the club’s affairs, once control of Celtic is allowed to be transferred from one group to another without interference.

Celtic plan future under Dempsey

The Scotsman 04/03/1994

By Hugh Keevins FOOTBALL CORRESPONDENT

IN a dramatic and decisive twist to the long-running Celtic saga, the board will meet this morning to discuss the future under the control of Fergus McCann and Brian Dempsey. The talks follow last night’s news that Celtic had been saved from receivership by the intervention of Dempsey, the director who was removed from the board four years ago. Should the directors, with the full approval of the Bank of Scotland, agree to the proposals put forward by the expatriate Scot, McCann, and Dempsey, the first item on the agenda is likely to be the abandonment of a move to a new stadium in Cambuslang – the brainchild of deputy chairman David Smith whose resignation is now being sought.

The latest sensational development surrounding the troubled club would at last seem to resolve the battle for control which has led to months of turmoil, culminating in the midweek boycott of Celtic’s home match with Kilmarnock. In a statement issued on behalf of the club last night, it was stated that the resignations of Smith, along with fellow director Christopher White, were being sought after a meeting with the Bank of Scotland. That meeting had revealed that ”the full financial plight of Celtic had been withheld from the full board.” The statement added that the club were in ”immediate and dire peril of being put into receivership.”

McCann has been unequivocal in his dismissal of the idea that the club should be transported from its traditional home to a new base on the outskirts of Glasgow. Dempsey has also called the Cambuslang development ”claptrap”, so he is certain to side with McCann on that issue.

The uncertainty over the future of another Celtic director, Michael Kelly, is sure to be fuelled by the re-emergence of Dempsey as a major player at Celtic Park. Dempsey has always believed Kelly to be responsible for his dismissal from the board, six months after joining their number, in 1990. Yesterday four directors of the club, Kevin Kelly, Tom Grant, James Farrell and Jack McGinn, met with the Bank of Scotland, the club’s main lender and mortgage holder. Smith and White have been accused of withholding from the board the full extent of Celtic’s financial plight. The club’s bankers told the four directors present that Celtic had been in ”immediate and dire peril” of being put into receivership.

The intervention of Dempsey has eased the club’s position in the short term. The only mystery which remains to be solved is the immediate future of another Celtic director, Michael Kelly. The man responsible for the club’s public relations was not present at last night’s meeting with the bank but neither has his resignation been sought. Last night Celtic’s chairman, Kevin Kelly, said: ”I am delighted with what has been achieved in securing the continued existence of Celtic Football Club and I look forward to determining the way ahead for the club with Brian Dempsey and Fergus McCann.

”The bank are also delighted with this solution which enables us to pursue the future we all wish for this club”.

McCann, a multi-millionaire, had, along with Dempsey and three others, deposited a total of 13.8 million in the Bank of Scotland last year as part of an attempt to wrest control of the club from the seven-man board of directors. At an extraordinary general meeting held last November, however, his proposal was defeated and he returned to Montreal saying he would only intervene in Celtic’s affairs once again if it were at the invitation of the bank. McCann is expected to arrive in Glasgow today and be reunited with Dempsey, the man who was a Celtic director for six months before being removed at an annual general meeting. Since Dempsey believes his dismissal was choreographed by Christopher White and Michael Kelly, he has vigorously pursued control of the club and now seems to be on the verge of achieving his aim. Celtic’s debts are believed to total in excess of 6million and their ground and team both need considerable sums of money spent on them as well.

Celtic on threshold of brave new age

The Scotsman 05/03/1994

By Hugh Keevins FOOTBALL CORRESPONDENT

A LONG DAY’s journey into night appeared to bring three directors, Michael Kelly, Christopher White and David Smith, to the end of the road at Celtic Park and apparently installed Fergus McCann and Dominic Keane as the architects of the troubled club’s new era.

It was Dempsey who made the most pertinent statement of the night when he was asked about the immediate aims of the new board.

”Don’t forget,” he said, ”the bank were ready to stop Celtic from signing cheques on Thursday. We have to go over the books and find out the exact financial state of this club before we do anything.”

Negotiations that began when the old guard arrived at the ground at 10am were still going on ten hours later with the details of the takeover at Celtic Park being notional.

The change that most supporters wanted to see, the removal of the three directors accused of mishandling the club’s financial affairs, looked like being achieved, however, by virtue of McCann putting up the money to pay for their shares. McCann, it is understood, could be chief executive on the interim board which will hold its first meeting next week. There is no doubt, though, that he will emerge as the new figurehead at the club. Keane, a banker by profession, is the brother of the Bermuda-based tax exile, Edmund, who was one of the five-man consortium whose bid to gain control of the club failed at an annual general meeting last November. Keane’s financial expertise will, in the event of a deal being finalised, be brought to bear at the club who, 24 hours before his appointment, had been told they were in ”immediate and dire peril” of going into receivership. The new director’s feeling for the club had him, on the last occasion we had met inside a football ground, incandescent with rage on the day Motherwell eliminated Celtic from the Scottish Cup at Fir Park in January. Keane will work to see that such days are not repeated in future.

The four directors who helped Keane and McCann realise their aims, Kevin Kelly, Tom Grant, Jimmy Farrell and Jack McGinn, look like retaining their places on the board after helping to engineer the downfall of the old order. What changes McCann ultimately has in mind remain to be seen but the Scots-born, Montreal-based millionaire has a hard-nosed, North American approach to business.

Brian Dempsey, the former director who was a central character in yesterday’s dealings, maintained an avuncular approach throughout a day of lengthy and delicate negotiations, periodically emerging at the front door to inform waiting fans of how talks were progressing. Dempsey’s future is also unclear. It is hard to imagine the man who masterminded the rescue package that saved the club from the ultimate embarrassment of foreclosure at the bank, and who has waited four years to play an active role at Celtic Park, having no practical part in the new era.

Lawyers, however, spent hours poring over the fine detail of the agreements that would effect historic change. Meanwhile, the directors, old and new, apparently dined on fish and chips.

Celtic’s manager, Lou Macari, normally the most pragmatic of men, was sufficiently caught up in the day’s doings to find himself unable to discuss this afternoon’s match with St Johnstone at McDiarmid Park. The manager cancelled his normal Friday press conference on the basis that there were ”other events taking precedence over the football”. It was a statement indicative of the way the new year has started at Celtic Park. The day that people get back to discussing the dressing-room as opposed to the boardroom will be the day Celtic have regained an air of normality.

Nightmare year draws to a close

The Scotsman 05/03/1994

By Hugh Keevins

CELTIC’s year, which officially started with the 3pm kick-off against Rangers on 1 January and saw the team lose a goal to Mark Hateley in the first minute, had been going steadily downhill.

Until yesterday. When Fergus McCann and Brian Dempsey entered a packed press conference last night, the former was taking control of the club two years after he had initially tried to buy his way into Celtic. Dempsey had been waiting since 26 October, 1990, to gain his revenge for the stage-managed refusal to ratify his appointment to the board that was produced on that date. Better late than never for the pair.

That was the attitude of the players who last night made no secret of their delight over the boardroom machinations which had given the club a fresh impetus. Charlie Nicholas and Peter Grant are Celtic supporters with jerseys and neither could conceal his delight over yesterday’s developments. Nicholas had been the only player to publicly disown the board in its pre-receivership form. Yesterday, he was equally forthright when welcoming in the white knights who had ridden to the club’s rescue as foreclosure loomed.

”The Celtic supporters now want honesty and integrity,” said Nicholas.

”Brian Dempsey is a personal friend and I cannot think of a better man for Celtic.

”There are players in the dressing-room who are not as familiar with the club’s background as Peter and myself, but I have been telling them that the new moves are a good thing for the club.”

Outside the ground, supporters who shared that opinion grew in number and there was an occasional outbreak of chanting. For the first time in months, they were favourable. The ‘sack the board’ ditty was redundant. It was unlike the chaos that had marred the New Year’s Day game, when one supporter had tied his scarf into a noose and dangled it in front of the directors’ box. Things got so bad thereafter that when the team went to Firhill to play Partick Thistle while in the midst of a seven-game run without a win, the directors brought their own stewards to guarantee their personal safety. The presence of the board had become a provocation to Celtic’s fans. Perhaps that explained the attraction of moving to a new stadium at Cambuslang. The directors’ box there might have been behind glass in the 21st-century vision that was explained to a bemused press by the old guard last Friday.

”It was sold to people as the greatest day in Celtic’s history, but it didn’t do much for me. I went home feeling depressed,” said Grant.

”Celtic Park is where our supporters have gathered a lifetime of memories. This club should not even consider the idea of moving anywhere else.”

Grant is still three weeks away from full fitness after suffering a bad knee injury in January. His wife is expecting their first baby next week. He sounded as if getting a new set of directors was as enjoyable as either of those experiences.

Celtic’s next home game is against Motherwell on 26 March. Grant, currently out injured, could be back by then; the supporters will certainly be back and in their thousands. They milled around the ground from morning until night yesterday and took delight in telling you that the cash withheld from the old board through boycotts would be given back in plenty through their attendance at home games. The final indignity had come when the fan arrested for running on to the park and attacking Rangers goalkeeper Ally Maxwell said in court that he wanted to get banned from Celtic Park.

The only break the old board had received, in fact, came when the SFA decided the club warranted no punishment for that incident becaue they had ”taken all reasonable precautions”. A pity, then, that they had not been so circumspect in their financial dealings.

Fans in paradise as Celtic’s saviours reach their goal

The Scotsman 05/03/1994

By Alan Dron

SURROUNDED by a scrum of well-wishers and journalists, Fergus McCann walked to the doors of Parkhead yesterday, posed for photographers, then disappeared inside to take over the reins of Celtic FC.

After months of acrimonious dispute with the club, the millionaire took control not through a head-on battle with the board he had tried to oust, but an invitation from its chairman, after the full scale of Celtic’s indebtedness had been disclosed to directors by their bank. It is understood that Mr McCann will be co-opted on to the board with one other new director after the resignations of the vice-chairman, David Smith, the secretary, Chris White, and another director, Michael Kelly.

Having flown to Glasgow from Phoenix, Arizona, yesterday morning, he arrived at Celtic Park at lunchtime. Struggling from the car amid the crush of photographers – one of whom had already fallen in front of the vehicle’s wheels – and blinking from the flash guns, he said:

”I can tell you the financial position of the club has been secured.”

Asked how he felt in his moment of triumph, he replied prosaically: ‘

‘I’m tired actually. I’ve been travelling for some time.”

To applause and cries of ”Fergus is the man” he went aside to take his part in negotiations for signing over control of the club. He had been preceded two hours earlier by his colleague, Brian Dempsey, a Glasgow builder. Asked if he had been invited to Parkhead by the board, Mr Dempsey said: ”It’s been suggested that I come along.” He was not interested, he repeated, in becoming a director.

”I hope all of us, whatever side of the fence we are on, will put Celtic first, personal and legal gain second.”

There had never been a more crucial weekend in the club’s history, he said.

Minutes before Mr McCann arrived, Matt McGlone, the leader of the Celts for Change supporters’ pressure group, emerged from the stadium’s front doors and quietly told his members: ”It’s done, finished, they are just waiting for Fergus to come to sign the papers.

Brian Dempsey’s grinning like a Cheshire cat.” Turning to elated spectators, he said: ”We’ve done it, you’ve all done it.” Fans were jubilant. One said: ”It’s a day we all thought would never come.”

Another, in a reference to the boycott by supporters of Celtic’s home games in protest against the behaviour of the board, said: ”The supporters will vote with their feet and be back through the turnstiles. You’ll see at the first home game on 26 March with Motherwell; it will be a total sell-out.”

However, as the afternoon wore on, a promised press conference detailing the day’s events was repeatedly delayed, as details of the deal were settled. It was believed last night that a six-man board would be formed, with Mr McCann as chief executive. Its other members would be the former club chairman Kevin Kelly, the directors Jack McGinn and Jimmy Farrell, the stadium director, Tom Grant, and a new recruit, Dominic Keane.

Charlie Nicholas, the player who has been most outspoken on events at Parkhead, said: ”I’m a personal friend of Brian Dempsey and there’s no better man. If things go the way I hope, it will be the greatest day Celtic have had for a long time.”

Sun shines again on Paradise

The Scotsman 05/03/1994

No Byline Available

IT WILL not be only supporters of Celtic Football Club who are relieved that it has been pulled back from the brink of oblivion. Had such a fate overtaken it, the repercussions on Scottish soccer and, through a broader focus, Scottish culture would have been serious.

Founded just over a century ago – its centenary season in 1988 was its last successful one on the field and in the profit and loss account – the club’s initial motives were not confined to sporting endeavour. It had a social objective, too, seeing itself as a means of providing charitable aid to the mainly Catholic poor of Glasgow’s east end. In short, it was from the beginning the ”people’s club.” And it was principally because those who ran it forgot the responsibilities that that involved, and allowed their link with the organisation’s supporters to atrophy, that it fell upon hard times. Their neglect, which all can see now, proved almost fatal.

There were, of course, other reasons for the speedy decline. If football these days is big business then Celtic’s directors were out of place. In recent years, they have tended to follow the initiatives of their great rivals, Glasgow Rangers, in the marketing field. Failing to make substantial financial returns from an organisation that could rely on the undying support of a significant proportion of Scotland’s population took a talent that would have struggled to make a going concern of a corner shop. That the club’s name is international was not seen as an opportunity to be exploited; it was as if the families who directed its fortunes could not see the potential of the vast family that, though it lay beyond Scotland, always thought of Parkhead as Paradise.

In some ways it is appropriate that it was from among that huge fraternity that the successful rescue bid was launched. No-one, especially perhaps the club’s supporters, should underestimate the size of the task ahead. Imagination and discipline will be needed as much in the boardroom as on the field of play. Through their display of dogged determination over the past few months, Fergus McCann and his associates have shown they have the character and the strength to overcome the club’s difficulties. And they have the financial resources, too. They know, moreover, that there are thousands of dedicated supporters, who have been willing them to victory over the old regime, anxious to help.

On the playing side they have a young manager and a team who, given the stable environment (and a new player or two) that the reconstructed, McCann-led board can furnish, could bring sunshine back to Paradise once more. There ought to be no complaints about that.

No Headline

The Scotsman 05/03/1994

By Alan Dron

JUBILANT Celtic fans celebrated outside Parkhead last night as control of the debt-ridden club passed into new hands.

The White-Kelly family dynasty, which has ruled the club for a century, finally relinquished power with control passing to Scots-Canadian tycoon Fergus McCann.

After 13 hours of intense negotiation, directors Chris White, Michael Kelly and vice-chairman David Smith all resigned. Mr McCann, who had failed with an 18 million rescue plan last year, said he intended to move back to Scotland and take up the full-time role of chief executive ”very shortly.” The other new board member, Dominic Keane, a banker, said he hoped to bring a period of stability to the financially-crippled club.

Not on the new-look board, but very much in a position of influence is Mr McCann’s colleague, Brian Dempsey, who has declined a board seat for the moment, but looks certain to take up such a position once the dust has settled. As the new board held a triumphant press conference at 11pm last night, fans were singing and sounding their car horns outside the stadium. However, Mr Dempsey, a Glasgow builder, was careful to stress repeatedly that he and the board were now looking for the club to enjoy ”a healing period” following the months of acrimony between the former board members and the claimants to their seats.

The three outgoing directors will all receive compensation for their shares, which allows Mr McCann to begin plans for refinancing the club which is currently over 7 million in debt. It would have gone into receivership this weekend if the rescue mission had failed. Mr McCann intends raising 17.8 million from a new share issue and his own personal wealth.

He said: ”I am delighted to be joining the board. Thankfully we have been able to resolve the critical short-term financing of Celtic and shortly we will be able to discuss a long-term package.” He claimed it had been a ”total victory” for the rebels who have long sought power: ”I can now tell the fans that the club is in safe hands.”

Praising the Celtic supporters who had helped bring the matter to a head, he said: ”The message I have for them is one of sympathy and appreciation. They have tolerated a terrible situation for far too long. I have a strong feeling that morale will soar from now on. I want to see Celtic back at the top where they should be.”

Mr McCann had arrived at Celtic Park at lunchtime after flying to Glasgow from Phoenix, Arizona. He had been preceded two hours earlier by Mr Dempsey, who said: ”I hope all of us, whatever side of the fence we are on, will put Celtic first, personal and legal gain second.” Minutes before Mr McCann arrived, Matt McGlone, the leader of the Celts for Change supporters’ pressure group, emerged from the stadium’s front doors and quietly told his members: ”It’s done, finished, they are just waiting for Fergus to come to sign the papers. Brian Dempsey’s grinning like a Cheshire cat.” Turning to elated spectators, he said: ”We’ve done it, you’ve all done it.” Fans were jubilant. One said: ”It’s a day we all thought would never come.”

Charlie Nicholas,

the player who has been most outspoken on events at Parkhead, said: ”I’m a personal friend of Brian Dempsey and there’s no better man. If things go the way I hope, it will be the greatest day Celtic have had for a long time.” Editorial, Page 8 New dawn, Page 24

No Headline

Scotland on Sunday 06/03/1994

By Francis Shennan

CELTIC fans, jubilant at the takeover of the club by Canadian Fergus McCann, will have to find at least £600 each to invest in the club. But they will be offered easy terms to buy shares, perhaps even by the bank whose pressure precipitated the change of control. McCann has also said the club’s constitution will be re-written to prevent the rise, or re-emergence, of any future Celtic dynasties.

Yesterday the Scots-born Canadian tycoon promised a thorough audit of Celtic’s finances stretching back several years, and lambasted the Bank of Scotland for their handling of the club’s worsening financial predicament.

”Celtic’s affairs should never have been allowed to get into such a mess. The bank should have stepped in earlier. I will meet bank officials shortly to register my complaint”.

Money from the fans is expected to bring in 5.4m. The major investors, including McCann and Brian Dempsey, will contribute 12.5m. But the club will still need to raise additional funding from bank loans and the Football Trust for construction work at the ground, which would take the total to 25-30m. The new management also anticipates spending more on players’ salaries and transfer fees over the next few years.

The number of shares to be issued has yet to be worked out but it will probably be between 2,000 and 6,000. Celtic will become a public company in that shares will be traded – it is unlikely to seek a stock market listing. Shares will probably be traded on a matched-market basis, where appointed stockbrokers match buyers with sellers. With an expected high demand from fans and the limited number of shares being offered, they are likely to trade at a premium.

A new constitution will mean that after McCann’s planned departure in five years, no individual, family or group will be allowed to own more than a limited proportion of the total share capital, probably 10%. The board’s right to veto the transfer of shares, which made Celtic immune from takeover will also be removed. McCann described such a veto as ”undemocratic”. until financial analyst, David Low, came up with the idea of acquiring proxy votes along with the shares,

Yet the club will try to introduce easy terms to allow supporters to afford the minimum investment of around 600. When the other half of the old firm introduced its Rangers Bond debenture scheme in 1990 it negotiated personal loan plans with the Bank of Scotland, Royal Bank of Scotland and the TSB Bank. The Bank of Scotland, owed between 7m and 10m by the club and ready to call in the receivers last week, has now been reassured by McCann and Dempsey and may well be asked to offer loan facilities to fans buying shares.

Celtic’s new boys set to face testing times ahead

Scotland on Sunday 06/03/1994

FOOTBALL OPINION By Kevin McCarra

CELTIC must now adapt to normality.

It will be an eerie experience at a club where the bizarre has been routine for many years. If the new proprietor, Fergus McCann goes about his business effectively the average fan will be shorn of conversation. A stadium with added seats and a boardroom minus strife hardly provoke animated discussion.

McCann’s plans will attract scrutiny, but attention must also now be spared for other aspects of the club. A life without excuses stretches before Celtic. It was hard to attack the funereal tone of the side when the club itself was dying. From now on, though, those mitigating circumstances have been removed. If the performances still lack panache the blame will lie with the players, some of whom were expensive purchases.

The relationship between team and manager is also certain to attract careful appraisal. It has so far proved impossible to pass any significant judgement regarding Lou Macari’s work at Celtic Park. Given stable circumstances, however, his employers will expect progress. He, of course, was not Fergus McCann’s appointment. Enquiries about Macari’s job security met with neither an endorsement nor a threat, simply a cautious reply. ”That,” said Brian Dempsey, ”doesn’t come into the question at this time.” McCann is also about to test the much-vaunted passion for the club which is said to permeate a vast but recently absent support. The all-important question is: just what numbers will turn up to cheer in future once the initial rapture is over?

The financial crisis which continues to face Celtic will only be resolved by the most intense degree of support from the paying public. The new director Dominic Keane estimates that as much as 40m of income, whether from investment, sponsorship or other activities, is required over the next two years to seriously begin the rebuilding of club, team and stadium. The Cambuslang project is certain to be ditched and Celtic will have to pursue the tiresome old routine of spending their own money to create a satisfactory ground. The club needs to boom if it is even to make satisfactory progress.

At present the turnover stands at 9m, less than half that of Rangers. McCann is peeved by the degree of decline and hinted that he blames the Bank of Scotland for delaying the action they belatedly took this week.

”They have been aware since November,” he said, ”that our money was in place.

”I will be looking into this. We are going to have discussions with the bank and there are some hard decisions to be made.”

Keane fended off the suggestion that the Bank of Scotland had been guilty of no more than generosity to the previous regime: ”They have a duty not only to the directors but also to all shareholders.”

McCann seems aggrieved he had to abandon his previous policy and compensate directors to secure their removal. He argues that the ”shotgun situation” which forced him to cut a deal as the bank threatened to put Celtic into receivership could have been avoided by earlier action.

McCann must marshall his forces as he confronts the many problems. The current board can only be an interim arrangement and there must, in particular, be questioning of Kevin Kelly’s position as chairman. He did show a true devotion to the club by turning down some 500,000 from Gerald Weisfeld so that he could hold on to his shares and support McCann. Still there must be disquiet over a chairman who did not become aware of his club’s true financial difficulties until the verge of bankruptcy was reached.

Despite the concerns a little jubilation still showed through McCann’s jet-lag as he set out for Perth yesterday. The new chief executive demonstrated considerable courage in lavishing money on so debt-ridden a club. It remains to be seen whether he can elicit an equally fervent response from those supporters who are about to share some tricky times with him.

Celtic emerge from shadows of despair

Scotland on Sunday 06/03/1994

Guiding light shines over field of dreams

‘Dempsey and Low, who turned down directorships, may be content to wait until a period of turmoil is complete’

‘Attempts to maintain a dynastic power structure set up conflicting forces which came close to pulling Celtic to pieces’

‘McCann completed all the paperwork at 11:52 on Friday. It was eight minutes from the bank’s deadline of high noon’

‘Friday was for the formalities. Smith, White and Michael Kelly were ready to stand down so long as they were compensated’

THERE’S an American ritual which follows every election; prosaic in itself, but eloquent of the transience of power. In the small hours of the morning, when the result is certain, the Secret Service moves in to protect its new president. It spoke volumes on Friday afternoon, many hours before the old guard finally capitulated, that Celtic’s burly security officer, George Douglas, was in the car park to meet Fergus McCann and guide him through the throng.

For two hours and a crucial eight minutes earlier, the only thing that really counted had been settled. That morning, Scots-Canadian millionaire McCann and his adviser, David Low, had dodged traffic in their PR man’s BMW to reach the Bank of Scotland offices in Trongate, Glasgow. The car, fittingly, was fire-engine red; they were bent not only on rescuing a debt-ridden Celtic but also on seizing control of one of the world’s great footballing institutions.

The day before, the bank had been on the point of calling in the receiver, and relented only when McCann’s consortium agreed to inject 1m immediately to control an overdraft erupting beyond its 5m limit. Frantic activity ensued as the money was located, transferred, converted to sterling and lodged in the Trongate branch. McCann completed all the paperwork at 11:52 on Friday. It was eight minutes from the bank’s deadline of high noon. The battle for Celtic ended with those strokes of the pen.