| Jock Stein Homepage |

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry

Stein, John[Jock] (1922–1985), footballer and football manager, was born at 339 Glasgow Road, Burnbank, Hamilton, Lanarkshire, on 5 October 1922, the only son (he had three sisters, one of whom died early) of George Stein, coalminer, and his wife, Jane McKay Armstrong. After leaving Greenfield School, Burnbank, at the age of fourteen, he worked briefly in a carpet factory before becoming a miner in the Lanarkshire coalfield, an occupation which he continued until 1950. He first signed for Burnbank Athletic in 1938 but never played for them: his father did not like the way the club had secured his signature and so he joined Blantyre Victoria instead. As a coalminer, Stein was exempt from military service, and during the disrupted football of the war years, he played for Albion Rovers, in Coatbridge, from November 1942, and, except for a brief period on loan to Dundee United, he played for Albion until May 1950. By then he had a wife and family, having married, on 3 October 1946, Jeanie Tonner McAuley, a creamery worker, daughter of John McAuley, coal hewer. Dissatisfied with his position at Albion, he then went south to play for the non-league Welsh club Llanelli, his first full-time professional appointment.

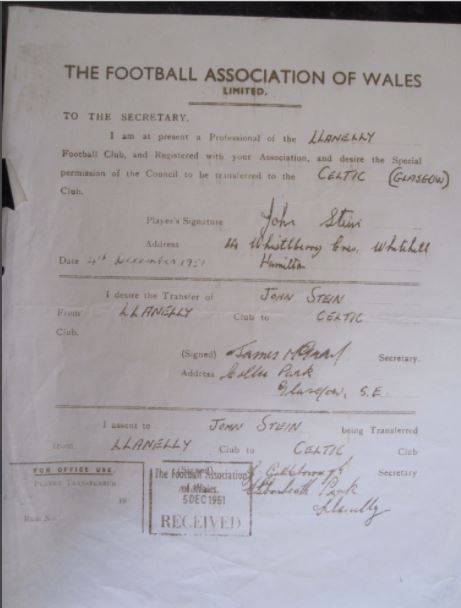

Unhappy away from his family in Scotland, Jock Stein, as he was now known, was attracted back north in December 1951 to coach the Celtic reserve team. An injury to two of the regular first-team players, however, gave him a place in the senior squad which he never relinquished until forced to do so by injury in January 1957. Although he lacked speed, and was very much left-sided, his height made him strong in the air, and his ability to read the game made him an accomplished centre-half, who was particularly effective at stifling opposing forwards. He also brought his long and hard professional experience to a Celtic team which was recovering from a poor spell on the field. Although it had several star players who helped to take it to mixed success in domestic competition and outstanding success in the two international competitions it entered in this period (1951 and 1953), the team Stein played for (and captained from 27 December 1952) never reached the heights of those he later managed.

When Stein’s playing career ended he coached the Celtic reserves from the summer of 1957 until he took up the position of manager of Dunfermline Athletic in March 1960. There he turned around the fortunes of the struggling club, saving it from relegation and then seeing it through to a cup final victory against Celtic in 1961. He took over as manager of Edinburgh’s Hibernian on 1 April 1964, but after a successful spell with them he returned to Celtic on 9 March 1965 as manager. The Celtic chairman, Robert Kelly, whose interference in running the team had contributed to its decline in the early 1960s, later claimed that Celtic had allowed Stein to leave the club to gain experience in his trade. This is a myth, but Kelly did make up for his mistake when he brought back to the club the man many thought should never have left. Stein soon made it clear that, unlike his predecessor Jimmy McGrory, he was in complete control of the team and would brook no interference from the board.

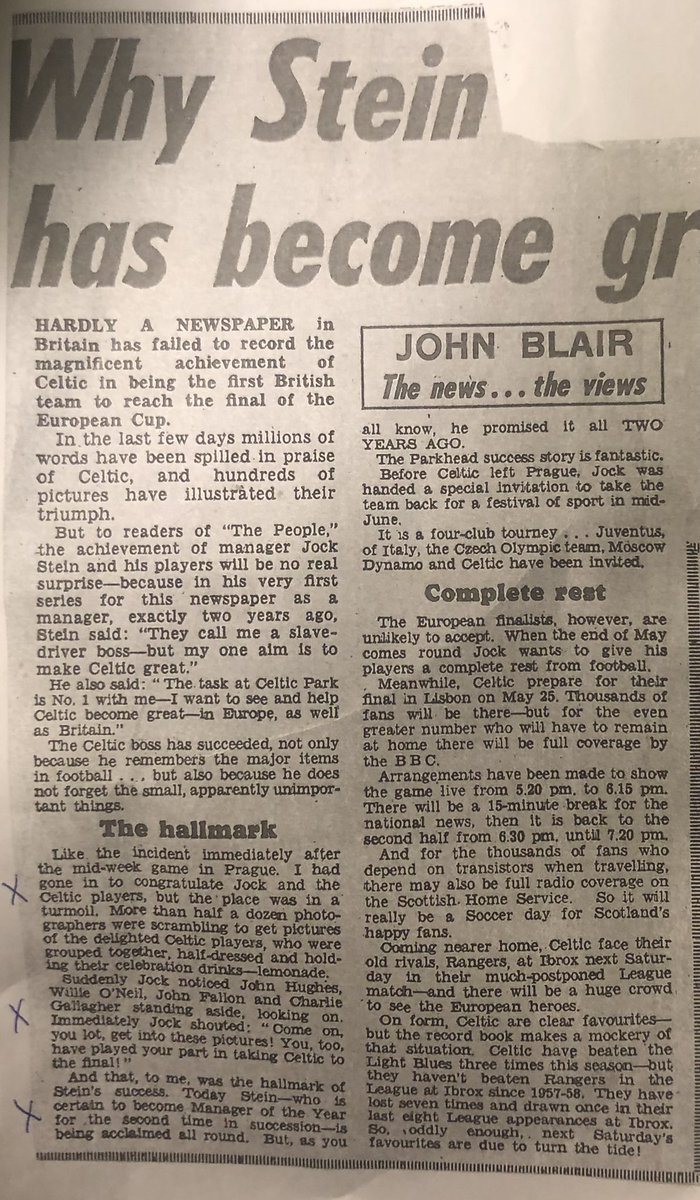

Within a couple of years Stein took Celtic on the first steps to domestic and European triumphs: in his twelve full seasons as manager, in addition to the European cup, Celtic won ten league championships, eight Scottish cups, and six league cups. Inevitably his name remains linked to the famous Lisbon Lions, a team whose most expensive player cost the club a mere £28,000, and all of whom were born within a 40 mile radius of Glasgow. This was the team that won the European cup of 1967 with a 2–1 victory over Inter Milan at the Estoril Stadium (Estadio Nacional) in Lisbon on 25 May 1967.

Stein lived for football and the players under his care, skilfully managing such wayward geniuses as Jimmy Johnstone and constantly planning new strategies. He was also a consummate manipulator of the press. His Lisbon Lions, in addition to winning the European cup in 1967 and being losing finalists in 1970, won a record nine successive Scottish league championships from 1966 to 1974. Above all, the Celtic teams of the Stein years lorded it over arch-rivals Rangers, whose team of the early 1960s had been one of the best ever. Despite success in the latter half of the 1970s, Rangers had to wait until the Souness years after 1986 to regain the ascendancy that Stein had taken from them, and in 1997 they equalled Celtic’s record of nine successive league championships.

Stein was Celtic’s first protestant manager, and only the fourth manager in the club’s history since its foundation in 1887. Although the club had always fielded protestant players, its origins and ethos were Irish-Catholic and this was a tradition protected by the family directors, all of whom were Catholic until the appointment of David Dallas Smith in 1991. Stein was offered a position on the board after he retired, ‘with a special responsibility for fund-raising’, but it was seen by Stein and many others as beneath the former manager’s dignity. Stein, who was married to a lapsed Catholic, nevertheless had several family and friends who came from Orange backgrounds, some of whom shunned him after he joined Celtic. Stein, himself totally free from bigotry, maintained an enigmatic attitude to Celtic’s Catholic traditions.

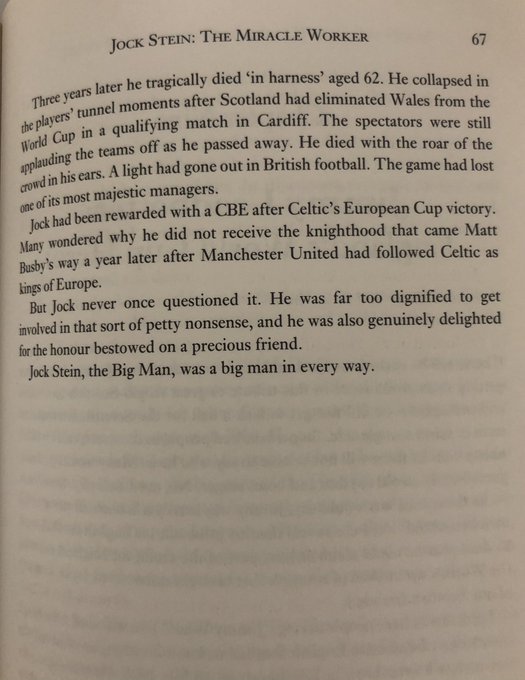

A strict teetotaller and non-smoker, Stein’s obsession with football took its toll and he suffered his first heart attack in 1973. In 1975 he was almost killed when he was driving a car that had a head-on collision; Stein was totally absolved from responsibility. He was never quite the same powerhouse after this. After a brief spell with Leeds United from 21 August to 4 October 1978, he accepted the position of manager of the national team. In this position he took Scotland to the world cup finals in Spain in 1982 and to the brink of the world cup finals in Mexico in 1986. Stein died of a heart attack at Ninian Park, Cardiff, on 10 September 1985, just thirty minutes after his team had all but qualified for Mexico with a 1–1 draw against Wales. His funeral took place at Linn crematorium, Glasgow, on 13 September; his wife and their son and daughter survived him.

Although only an average player, as a manager Stein was the equal of his legendary compatriots Matt Busby and Bill Shankly. He also shared with them the personal experience that playing football was a much cushier job than a life down the mines. To the fans, Stein remained a giant figure, the Big Man. At Celtic Park the Jock Stein lounge was named in his honour, as was the west stand which completed the renovations of Celtic Park in the summer of 1998.

Bill Murray: Stein, John [Jock](1922–1985)’,Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/40245, accessed26 July 2011]

Sources

R. Crampsey, Mr Stein: a biography of Jock Stein CBE, 1922–85(1986) · K. Gallacher,Jock Stein: the authorized biography(1988)

Wealth at death

£172,674.95

Strong case for asking Jock Stein to take over Scotland job

By IAN ARCHER

Glasgow Herald Monday December 25 1972

SPORTS HERALD

Scottish football possesses one man strong enough to carry the country into the final stages of the 1974 World Cup. There are no Christmas Day prizes for guessing that his office address is 97 Kerrydale Street, Glasgow.

Jock Stein should be asked as a matter or pressing urgency to take over the post deserted by Tommy Docherty last week. If he accepted, Munich once more becomes an attainable dream.

It seems sensible to ask the most influential figure in Scottish football to take over the most prestigious job that the country can offer. It is also the exact step that the fans expect the SFA to take.

I will submit the following case that the football authorities should put to the Celtic manager this week as they settle down to the business of sustaining the rich inheritance that Docherty left behind him after only 14 months in the job.

Scotland is presently in a state of some crisis in footballing terms, with players and managers emigrating and the fans vanishing from the terraces the game is in need of some impetus from its national side if interest is to be maintained in the next few years.

A Scottish team in the World Cup finals would help to invigorate the game at large and in that respect the management of Scotland in the next 18 months becomes the most crucial task of anyone inside one corridors of football.

Stein has often made the same point. He has built Celtic into one of the world’s most feared clubs, but so often he has brooded with frustration at the football formula that surrounds him inside the country. It is vital for his club that his country should do well.

So it should be the SFA case that Stein should be taken from Celtic on an extended sabbatical that would ensure the game at club level does not suffer because we drop out of the one competition that can rally people round the television sets in the summer of 1974. A new audience awaits football if it can accomplish this end, and Stein is clearly the man to see that this aim is achieved.

It would mean a sacrifice by Celtic, but one that could maintain some eventual prosperity for the game to which they would share. Scottish football would Iong remember them with affection if they were prepared to offer Stein’s services at a time when they were needed most.

Any new Scottish team manager needs to command instant respect. The fixture list that confronts the national side in the following months is either full of promise or beset with cruel traps, depending on the kind of results that can be gained.

In less than two months England arrive for the centenary International. West Germany and Brazil follow in 1973 and there is also the home International championship. Two World Cup qualifying games against the Czechs complete a programme which could have delightful or disastrous consequences.

Stein would gain the immediate trust of the senior players who will form the Scottish pool. That is more than can be said, with all respect to some of the names that are already being canvassed. The English-based professionals who will form the bulk of the pool, know precisely the merits of any new manager.

The Celtic manager is known and admired by them. He could start building up the momentum that has for the moment departed, and by filling Hampden for the big games he would pay for his own salary and leave a profit as well. That is important, considering the state of the SFA finances.

Stein might find it a challenge he could not refuse, bearing in mind that no fresh fields await him at Celtic. He is the best Scottish manager, and therefore should be given the best Scottish job.

If he refuses to take the job the outlook is bleak. Only Bill Shankly of Liverpool, and Eddie Turnbull of Hibernian are Scottish-born managers with sufficient pedigree and accomplishments to take the job. Frankly, the others will not do.

In that situation, with refusals from the top men the SFA should consider a revolutionary change of attitude. Does Scotland’s manager need to be a Scot?

IMPORTANT POINT

With the majority of the players coming from the English first division, the people who make the appointment should consider the possibility of trying to attract a top English manager to fill the post. The important point is to send a Scottish team to Munich, not to bother too much about the manager’s birthplace. Other countries use emigree managers.

The SFA, occasionally a much maligned body, showed enterprise in appointing Docherty and it was no fault of theirs that his remarkable spell should have ended too soon. They have also shown themselves in a good light by refusing to accept Docherty’s suggestion that he should carry on in a part-time capacity.

They know the prize that could await them in 18 months time is huge and now they must debate important issues which might overwhelm them. We should offer them our best wishes in the next difficult weeks.

A public approach to Stein would help because that would show that they want only the best man and not some palefaced substitute. If that fails, they should scour the world, for the opportunities are limitless, the penalties for failure enormously high.

Jock Stein’s arrival changed the course of Celtic’s history

By: Joe Sullivan on 09 Mar, 2012 07:37March 2012, Celticfc.net

THE month of March, 1965 could be described as the making of the modern-day Celtic. It was on this day, March 9, that Jock Stein arrived at Celtic Park,taking charge of his first Celtic game as manager just 24 hours later, with the legendary Jimmy McGrory stepping aside to pave the way for the most successful period in the club’s history after years of mediocrity.

However, success wasn’t guaranteed and for a club that had only ever had three previous managers in its nigh on 90-year history, this was, despite Stein’s burgeoning reputation as a manager who was going places, still a massive step in the dark considering there were half-a-dozen clubs or more who could rightfully expect to finish above Celtic in the title race in the early part of the decade.

The early 1960s, at least, certainly weren’t swinging for Celtic supporters and at least the swathes of barren years in the 1950s were at least interspersed with odd smattering of trophies.

However, elements of the fleeting successes of the previous decade could be attributed to the on-field man-management of team captain Jock Stein and when he switched to reserve coaching in that latter part of the ‘50s, there was a renewed sense of belief among the youngsters he was signing and tutoring.

That conviction had started to wane, though, as with Stein off on his managerial travels to work his magic with, first Dunfermline and then Hibernian, any self-assuredness in the young players breaking through was all-but knocked out of them by Mr McGrory’s compliancy with a domineering chairman in Bob Kelly whose slapdash interference in team selection had certainly cost Celtic games and, reportedly, trophies.

So much so that the blossoming youngsters who were being choked under the weight of the board’s inane playing policy, such as Billy McNeill and one or two of his team-mates, were casting their vision further afield and were tempted by the interest of prying eyes from down south.

But, not only did the arrival of Stein arrest this distinct possibility, if we are to believe the rumours, it actually reversed it as it has been suggested that Bertie Auld, who had left for Birmingham City in May of 1961 for £15,000, had been tipped a wink about Stein returning and, on hearing the news, the midfielder was literally ready to cartwheel back to Celtic Park to sign on January 14 for £12,000.

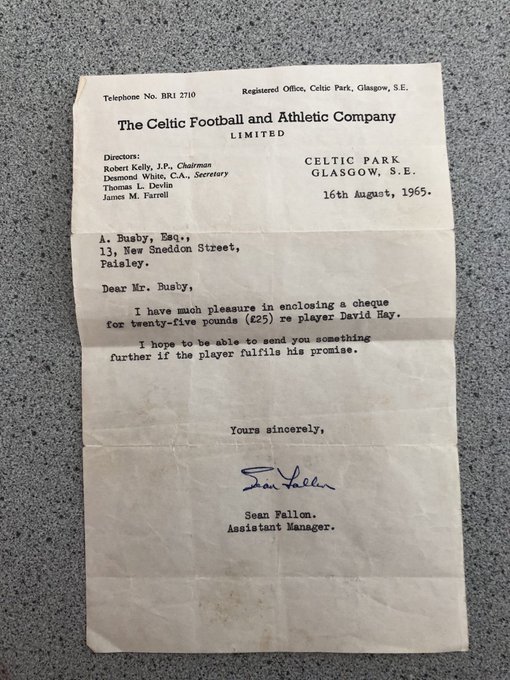

Officially, it was announced on January 31 that Stein would be returning as manager with Jimmy McGrory taking up the post of Public Relations Officer and Sean Fallon, who would have been a top candidate for the manager’s job himself, changing his capacity as chief coach to assistant manager.

However, it wasn’t an immediate move as Hibernian still knocking at the door of the championship and yet deep in the throes of Scottish Cup involvement were keen to hold on to Stein as manager for as long as possible.

If the Celtic players were boosted by the imminent arrival of Stein (just 24 hours before the official announcement they crushed Aberdeen 8-0 with John Hughes scoring FIVE of the goals wearing Billy McNeill’s sannies on the rock-hard icy surface), they were ironically afforded a probable greater boon by the fact that Stein wasn’t leaving Easter Road right away.

In the Scottish Cup quarter-finals, while Celtic were beating Kilmarnock 3-2 to move on to the semis, Jock Stein’s last act as Hibernian manager was to knock Rangers out of the tournament with a 2-1 win in the capital.

It would be an understatement to suggest that this result made any possible path to their first Scottish Cup glory in over a decade slightly more attractive – in the mind’s eye and on paper at least.

A few days after watching his charges in green and white oust the cup-holders at Easter Road, Stein ran the rule over a different set of players in the same colours as his new Celtic side took on Airdrie at Broomfield on March 10.

It was John Hughes who had the honour of scoring the first Celtic goal under Jock Stein when he netted in the 25th minute but it was the Prodigal Son in the shape of Bertie Auld who grabbed all the limelight by scoring the other FIVE in the 6-0 win.

The Celts, especially with the current joie de vivre around Paradise that was instantly transplanted with the return of Stein, still had an outside sniff of the title but following that 6-0 trouncing of Airdrie, in the eight remaining league games, the new manager chose to field six different line-ups as he searched for his favoured XI.

Seemingly, results were not the preferred be-all and end-all as the nearest Stein came to repeating that win was a 4-0 win over old charges Hibernian while the only other points garnered were in a 1-0 win over Third Lanark, thanks to an own-goal by former Celt Dunky McKay in what would be the last time the clubs ever met, and a 3-3 draw with Dundee.

The other four games didn’t make for good reading at all with a 2-1 loss to Partick Thistle being the best result from those as the others, a 4-2 home defeat to Hibs, a 6-2 loss to Falkirk at Brockville and a 5-1 slap by Stein’s other old club, Dunfermline at East End Park in the final game of the campaign didn’t bode well at all for the future.

However, that reverse in Fife could, if any apologists were so inclined, be laid firmly at the door of a hangover from a game that was played four days earlier.

Stein may have kicked over a significant hurdle for Celtic when his Hibs side knocked Rangers out of the cup but, clearly, there was still a lot of work to be done if any success was to be gleaned from the Hoops’ current cup campaign.

In the semis, as Celtic drew 2-2 with Motherwell in front of 52,000 at Hampden on March, 27, two of Stein’s old sides faced up to each other at Tynecastle and a 33,305 crowd saw Dunfermline win 2-0.

Four days later, 59,959 turned up for the replay and this time the Celts recorded a 3-0 win over Motherwell – the only side from the four in the semi-finals that hadn’t been managed by Stein in the previous 12 months.

That paved the way for a repeat of the 1961 final when Stein’s Dunfermline bested Celtic after a replay to lift the trophy for the first time in their history.

However, move forward four years and It was around 4.35 or so on April 24, 1965 that Celtic’s history changed irrevocably.

A crowd of 108.800 saw Dunfermline take the lead and lose it to a Bertie Auld equaliser before the Fife side took the lead once more to go in 2-1 ahead at the break. Auld equalised again seven minutes after the turnaround and the sides were on stalemate until Celtic earned a corner nine minutes from the end.

Charlie Gallagher swung over the dead-ball from the left wing at the Mount Florida End and then came the defining moment as Billy McNeill rose like a salmon to head home one of the most important goals in the club’s history.

Exactly 11 years to the day when Celtic had last won the Scottish Cup and captain Jock Stein strode up the Hampden stairs to raise the trophy aloft, the same man now stood as manager and watched Billy McNeill make the same short journey – but this was the start of a journey that was to was to stretch out farther and to more destinations than any Celtic supporter could ever envisage.

Interview 1972

Stein Says: I don’t threaten my players about long hair, I just tell them if they don’t get it cut they might not fight themselves in the team.

Stein Says: Some of the players today are as good as the old immortals, there just aren’t that many of them. Modern players are becoming blase with international travel.

Real Madrid, the Milan Clubs and Benfica where once the most sought after clubs in Europe. But not any more, Celtic manager Jock Stein told me this week.

‘Now we call the tune’ said Stein. ‘When anyone wants to play us in a benefit or a friendly I say okay, but only at our price. On our first trip to North America for instance, we travelled from one side of Canada to the other and from the coast of America to the west coast and ended up in Bermuda for a holiday.’

‘Last time we went to Toronto to play AC Milan and played before 34,000 people – a national record. We made more money in one match than we had done in the previous eleven in an exhausting tour plus a holiday in Bermuda. When you’ve goy a commodity to sell make it the highest you can get.’

And what is Celtic’s price for fitting another game into an already tight schedule ? £10,000.

Remember people whistled when the great Real Madrid side asked for and got the same amount. Few of us thought we’d ever see the day a Scottish club could name their own terms. Celtic and Stein have done it.

Already the Celts have obliged West Ham (Bobby Moore) and Man Utd (Bobby Charlton) for benefit matches. The latest club to make an approach is Chelsea on behalf of Scottish international full back Eddie McCreadie. There have been other offers that Jock didn’t mention, many from overseas including America and Canada.

‘Money keeps things going, the domestic scene at present makes it difficult for clubs like ourselves and Rangers to put money in the bank. Unless there is a drastic re-appraisal Scottish football will die. It’s dying now.’

‘We’re getting too much football but the fans will pay to see it on a big scale.’

‘In England the home clubs keep 80% of the gate and the away 20%. In Scotland it’s on a 50-50 basis. That’s all right for the wee clubs but in fairness to such as the Old Firm what do they get out of these games ? Not enough to make ends meet.’

Therefore how can the Scots compete with English gold ?

Stein: ‘We have to sell so many players that we are being drained. The day will come when England will subsidise our international team. We’ll have to go cap in hand and ask for their players. They’ll be able to ask us what we are contributing at international level. All done by their players, bought by them and trained by them.’

Then he said significantly ‘If the game is dying up here then I don’t want to be part of any dying sport.’

Stein figures we need an elite league, one with a tidy number of select clubs, successful clubs. ‘Study the form over the last couple of seasons. If a club is on the slide relegate it into another league and let’s have a third league if we have to. Under the present circunstances the tail is wagging the dog. We should get right down to rewriting the constitution and the rules. What was good in 1890 is antiquated today. There wasn’t TV, golf, bingo or any of the other extras to compete against not to mention rising costs.’

‘And another thing, the clubs moan about costs but they aren’t helping themselves. For instance the grounds stand vacany six days a week and in the case of those without reserves, thirteen days a fortnight. They could stage a number of things, bingo for example. They’ve got to think or go under.’

A man of action and a successful man at that, I reckon Stein could have been a success at almsor anything. He’s an ideas man.

‘Any club lucky enough to buy a new stand should build a complex of offices and shops and let them pay for the rent and rates to the ground.’

On sponsorship he’s all for it but let’s do it in a big way and not for peanuts. ‘Take Scotland’s top four clubs and England’s top four clubs and see what happens. For the other tournaments we’d rather not play in them. We don’t need the money but others do – badly.’

‘The top eight clubs in Britain should be able to makr it a football festival at the end of the season and not at the beginning. ‘If somebody puts up say £200,000 they’d get a lot of effort and a lot of football from by players who by that time will be tuned in.’

With forward thinking people like Stein I would suggest that the managers of Scotland get together and demand to be represented on all SFA and league commitments. I understand there is a move to do just this,

With pros guiding the amateurs then maybe we could get Scotland off the ground. We haven’t had a new idea since someone wrote the rule book 100 years ago.

Former Hibs doctor reveals he convinced Jock Stein to take Celtic job

By DALE MILLER

Edinburgh Evening News

source: http://www.scotsman.com/edinburgh-evening-news/latest-news/former-hibs-doctor-reveals-he-convinced-jock-stein-to-take-celtic-job-1-2690054

Published on Thursday 13 December 2012 12:04

IF not for former Hibernian doctor Gordon Batters, one of Scotland’s greatest football managers – Jock Stein – may never have ended up at Celtic at all.

Stein’s achievements are etched in sporting folklore.

He became the first manager of a British side to win the European Cup, achieving the feat with Celtic in 1967.

The centre-half also guided them to nine successive Scottish League championships between 1966 and 1974.

However, little known is the fact that Stein agonised over taking up the offer to become manager of Celtic – a secret that has been locked away for decades with Mr Batters.

These days the 98-year-old GP is living at Royal Blind’s Braeside House aged care home in Liberton, having lost his sight just two years ago.

But during the 1960s he was a man of influence at Hibs, with the experienced East Linton GP revealing he had been a close confidante of Stein during the manager’s successful two-year stint at the Edinburgh club.

Mr Batters said: “I worked for Hibs for about 14 years.

“It was the end of the Famous Five period. Hugh Shaw resigned as manager and we had several different fellows after him, but they never lasted long. Then we had John Stein. You’ll know him as Jock – he hated the name, so we called him John.

“He and I were always quite friendly. One morning I was phoned up twice – one was from John himself to ask if I was coming up to the club. The other was from his wife, Jean.

“When I went up to the club he’d just been visited by Mr Kelly from Celtic, who had offered him the job as a manager. But he’d only been 11 months with Hibs and he felt a bit guilty at saying yes. He asked me what he should do.

“I said ‘John, you’re a Celtic man, you’ll regret it if you don’t go’, especially with terms such as the ones he dictated to me. He was offered freedom to sign [who he wanted].

“Jean was very much against it, but I said ‘he is a Celtic man and should go’ . That’s one of the things I shouldn’t be telling you.”

Opened in 1999, Braeside House is an award-winning care home for older people who are registered blind or visually impaired. The service is run by Royal Blind – the charity being supported in this year’s Evening News Christmas Appeal.

The campaign is aiming to raise as much as possible to help provide vital equipment and funding for the many services the charity provides.

Mr Batters, originally from East Linton, is one of about 70 residents living there.

Note: Counter to what Gordon Batters has said that Jock Stein’s wife was against the move:

John McLauchlan @Coreybhoy2 · Feb 8 Replying to @joebloggscity “She wasn’t against it she was for it. It was when Pat Crerand was in Jock’s house in Southwood Drive and tried to tap him up about going to Man Utd she said she wouldn’t be going there and that was before he got to Jock.”

Glenn Gibbons: Ferguson says Stein was the greatest

The Scotsman

http://www.scotsman.com/sport/football/english/glenn-gibbons-ferguson-says-stein-was-the-greatest-1-2926229#.UY4hMNYeGpg.twitter

By GLENN GIBBONS

Published on 11/05/2013 00:20

OF THE avalanche of tributes and criticisms directed at Sir Alex Ferguson since the announcement of his retirement, the most commonly used superlative is the one at which he is most likely to bristle.

That is, the frequently bestowed acclaim of the Govan man as “the greatest manager in history”, an appendage which he himself believes, with a reverence that approaches sacredness, to be the rightful preserve of Jock Stein.

Even after almost 40 years of virtually unbroken distinction north and south of the border, Ferguson maintains that his happiest days as a manager were those he passed as Stein’s assistant with Scotland’s national team in the 1980s, once offering the startling confession that “I would have happily remained big Jock’s assistant for the rest of my days.”

Ferguson reflects many of the qualities the former Celtic manager brought to a profession in which he was an authentic pathfinder, not least an irresistibly forceful personality driven by a formidable intelligence and seemingly limitless energy. But he has always insisted that nobody, including himself, has come close to the natural charisma that made Stein the most seductive and persuasive figure of his lifetime. This is hardly surprising to those of us fortunate to have kept the company of both men through decades of incalculably rewarding relationships that brought immeasurable enrichment to the business of chronicling their staggering achievements. Both endowed with a capacity for ferocity (natural and contrived, depending on circumstances), they also had in common a mischievousness that was no respecter of status or reputation and a peerless judgment of character and talent.

Stein’s towering influence on those around him is fascinatingly illustrated by an episode that occurred during a Scotland trip abroad when Jim McLean was Stein’s assistant. Several younger managers, including Ferguson, were invited aboard by the SFA, an opportunity to observe and gain useful experience. On the first night, with Jock at the centre of the gang and debate and argument flowing, the big man silenced the gathering with a challenge: “Okay, here’s one for you,” he said. “What’s the difference between a good player and a bad player?”. That prompted a buzz of conversation and a series of analytical musings, to all of which Stein responded with a disapproving, “Naw, naw, you haven’t got it.” After a while, he surprised everyone by declaring that he was off to his room, leaving them to ponder and discuss the question.

The surprise sprang from the common knowledge that big Jock was a terrible sleeper, more likely to keep others out of bed than retire to his own. The following morning, Brian Scott, the Celtic and Scotland physiotherapist, was first at breakfast, as the medical men usually are, in order to make early fitness checks.

Stein was soon with him, asking Brian what had happened after he left and what the various “thinkers” had come up with. Scotty reported everything, eliciting from Stein another shake of the head. “Okay, what is the answer?” Brian blurted, by this time curious to distraction. “A good player,” said Stein, “sometimes gives a bad player a loan of the ball.” It is a story which exposes the essence of Stein, and not merely through the wit and conciseness of the definition of the distinction between the gifted and the mediocre. It was, much more tellingly, in his spearing of Scott for information, his singular method of intelligence gathering, leaving himself fully equipped in readiness to meet the others, already knowing what they had been thinking. This was a brilliant propensity for interrogation that made Stein virtually omniscient – and one of which Ferguson himself had first-hand experience. During a long conversation in his office at Carrington a few years ago, occasioned by my assignment to deliver a piece on Ferguson talking about his mentor, the Manchester United manager reminisced with undisguised delight on the times spent with Stein, including those occasions when he became one of the big man’s victims.

“When I was a player at Rangers,” said Ferguson, “Cathy and I would occasionally have a Saturday night dinner at the Beechwood, the pub/restaurant next to Hampden Park that was managed by Kenny Dalglish’s father-in-law, Pat Harkins. Jock and Sean Fallon, his assistant at Celtic, would take their wives there every weekend, as they both lived nearby in King’s Park. Well, any time Jock spoke to me, I would feel ten feet tall. It was magical. He would ask me how things were at Ibrox and I would tell him everything I knew. Utterly helpless, it just came out without my even realising it. That was the effect he had on people. It was no surprise that Jock kept Celtic ahead of us at that time. He knew everything that was happening at Rangers because I told him!

“Years later, when I was a fully-grown man, a manager at Aberdeen, winning major trophies, and his assistant with Scotland, it would still happen. He would give me a ring on a Friday night and simply say, ‘How you doing? What’s happening?’. And I would tell him everything that had happened that week. I would pour out everything, because I would think he already knew what was happening and if I didn’t fill him in, he would think I was holding out on him! That was the effect he had on people and it was no wonder he knew everything about everybody.”

It was, of course, Jock who recommended Ferguson to the late Chris Anderson, then vice-chairman of ?Aberdeen, as the replacement for Billy McNeill when the latter left Pittodrie to succeed Stein himself at Celtic in 1978. It would be enough in itself to warrant universal recognition of ?Jock as the soundest judge that ever drew breath.

Incendiary arrival at Parkhead fuelled Jock Stein’s Old Firm passion

By Sportsmail Reporter

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sport/football/article-2933865/Incendiary-arrival-Parkhead-fuelled-Jock-Stein-s-Old-Firm-passion.html

Published: 23:42, 30 January 2015 | Updated: 23:42, 30 January 2015

View comments

It was 50 years ago on Saturday that Jock Stein was announced as Celtic’s new manager. And yet, as broadcaster and author ARCHIE MACPHERSON argues here, the Big Man’s shadow still looms large over an Old Firm fixture which returns to the Scottish footballing calendar on Sunday after a near three-year absence.

The simple announcement made by Celtic on the evening of January 31, 1965 — that Jock Stein would leave Hibernian and become their new manager — masked the emotional turmoil which preceded it. Perhaps, in its very brevity, it nervously anticipated the ferment that would immediately be provoked.

It was an assumption that was well founded. For all other factors, including Stein’s amazing success with the Easter Road side and Dunfermline, were subsumed under the weight of garish headlines declaring he would be the club’s first Protestant manager.

Few people at the time would have known there had been a stand-off in negotiations before that epochal decision, as Stein revealed to me in later years and about which he was almost embarrassed to admit.

Bringing Jock Stein (left) to Celtic as manager was a giantbreak with tradition

In historical perspective, the opposing stances taken by Stein and Celtic chairman Bob Kelly as they mulled over options might now seem as nonsensical to this current generation as arguing over who gets which side of the bed in a pre-nuptial agreement. The club were simply reluctant to relinquish a tradition which, as it stood, could not embrace Stein’s social background; an issue that the passing of time has dissolved into meaningless mumbo jumbo.

In retrospect, there was only ever going to be one outcome. Yet Celtic clung to the idea that Stein would accept being shepherded in the back door as assistant manager to Sean Fallon, or, as an alternative, share the management, which were the two options they proposed.

But the then Hibs manager was in a strong bargaining position and he knew it.

Celtic were floundering. They had failed to win the Scottish Cup in 11 years. They had triumphed in the Coronation Cup in 1953 against top English opposition but in the Scottish First Division they were being treated more often than not as mere punchbags by Rangers. They also took regular beatings from Hibs and Hearts as these clubs went on to win titles, too.

By comparison they had claimed the championship only once in 19 years.

Celtic supporters had by then taken on the posture of classic stoics, with attendances just before the end of that January rarely reaching 20,000.

Stein enjoyed absolute control over team matters and Celtic reaped the rewards

They were not slow to demonstrate either, as I experienced myself standing on the commentary platform just in front of the directors’ box. Kelly had torrents of abuse heaped on him which, to summarise in a Cromwellian manner, amounted to: ‘In the name of God, go!’

Stein was aware of that and coolly held out for his terms of absolute control over team matters, whilst introducing a threat that he would accept an offer from Wolverhampton Wanderers in England if it all became too protracted.

Celtic caved in and, in doing so, allowed this man to haul them into modernism at a rate which, even with the passing of time, is still difficult to comprehend.

For within two years of that January day in 1965, a club which had been treading the boards like a fourth-rate variety act became European champions. Baldly stated like that, it is the nearest to footballing alchemy ever contrived.

How was it all possible? Could it have simply revolved around one man’s ability to manage? You would not be laughed out of court in making a case for that.

Stein landed at Celtic Park in March with an innovator’s energy that upstaged his peers, who would have worn a tracksuit only as a Halloween costume, if at all.

His mud-spattered black one symbolised his need to be in the trenches as a communicator and demonstrated that his intimacy with his players was the basis of his motivational powers — a mix of Machiavellian cunning and, not infrequently, brutal intimidation.

Celtic manager Stein (centre) calls the shots at Barrowfield training during 1965/66 season

He had other strengths. He had grown up with a Rangers background and fully appreciated what it was like to be shunned — even by old friends when he left that tradition behind. In a parochial sense, that accounted for the personal drive that lay behind his preparations for any Old Firm game which, as Billy McNeill admitted to me, was a fixture that Stein always saw as possible retribution for some of the indignities he had endured.

This in itself does not account for the success in Lisbon in 1967, but it suggests that it provided a psychological basis for the hunger to succeed at any level to prove his worth and to assuage the lingering and profound hurt he felt at his father’s lack of support for his new identity.

So this was a complex man who transformed Scottish football as a whole. Others copied his strategies both on and off the field, most notably Alex Ferguson who saw Stein not just as a football manager, but truly as some kind of impresario who was there to shape and promote the identity of a club. He mirrored that and, like Stein, became a master of self-publicising, always within touch of a spicy headline.

Such managerial status of that magnitude is no longer with us. Certainly not at Hampden tomorrow when Ronny Deila is still under scrutiny by his own support and Kenny McDowall is merely filling a vacuum.

What influence that will have on the game is difficult to judge, even though Rangers appear to be in disarray. Overall, I suspect the game will simply remind people like me how lucky we were to be around when giants strode the land.

The Big Man

by Roddy Forsyth, 9th Septrmber 2015

If British football had a Mount Rushmore, Jock Stein would be one of its monumental faces. Three decades of weathering have not eroded the scale of his achievements. Rather, the 30th anniversary of his death on Thursday should remind us that he played a pivotal role in European football and that a similarly epochal change in British society arguably hastened his demise in a fashion which is almost inconceivable for today’s cohort of technocratic coaches.

The sense of Stein as an imperishable football presence was reinforced by a powerful and poignant address by Sir Alex Ferguson at the official dinner before Scotland’s Euro 2016 qualifier against Germany at Hampden Park on Monday night. Members of the Stein family, down to his great-grandson, were present to hear Ferguson’s tribute in a week of commemoration which began with a charity match between Dunfermline and Celtic, Stein’s first and last clubs as a manager in Scotland.

The Hampden event was the SFA’s acknowledgement of Stein’s time in charge of Scotland, during which he took the team to the 1982 World Cup finals in Spain and steered them into the play-off for Mexico ’86 when he was struck down by a fatal heart attack at the end of a febrile qualifier against Wales at Cardiff’s Ninian Park.

It was Scottish football’s JFK moment, the loss of a charismatic figure in shockingly public circumstances, so powerful that the recollection remains vivid across three decades. That is only the span of a single generation, yet Stein – like his similarly legendary countrymen, Sir Matt Busby and Bill Shankly – represents an era which now seems vanishingly distant.

One singular connection between the three is that they were miners, but Stein worked longest as a collier, the experience which principally shaped his philosophy of life, as well as football. Stein’s supreme achievement, of course, was to become the first British manager to win the European Cup with Celtic’s epic victory over Inter Milan in Lisbon in 1967.

The triumph was famously accomplished with a team born within a radius of 30 miles of Glasgow city centre – and it would have been 12 miles, but for Bobby Lennox seeing the light of day in the seaside resort of Largs. That fact alone renders the Lisbon Lions unique in the annals of European football but the wider impact of Celtic’s success is still usually underestimated.

Until Stein’s players prised it from their heartland, the European Cup had for 11 years been solely the possession of Latin clubs – Real Madrid, Benfica, AC Milan and Inter. After Celtic bore it back to the east end of Glasgow the trophy remained in northern Europe for all but one of the next 17 seasons, as Dutch, English and German clubs asserted their dominance.

The chapter of almost unbroken northern superiority came to an end in the summer of 1985 in circumstances which arguably hastened Stein’s death when Juventus beat Liverpool at the Heysel Stadium to win Europe’s premier competition for the first time. Their victory was eclipsed by the crowd disorder which saw 39 Italian fans killed and more than 600 injured when a wall collapsed as they were charged by Liverpool fans.

English football, already reeling from the deaths of 56 fans in the Bradford Disaster less than three weeks previously, was placed in a quarantine that saw clubs banned from European competition for five years. At home, too, the game was assailed by Margaret Thatcher’s government, flushed with victory in the miners’ strike and up for another confrontation, although football casuals were inchoate by comparison with the National Union of Mineworkers.

The government began to float the idea of ID cards for fans, a notion which was included in the Football Spectators’ Act (1989), although never implemented. Throughout the summer of 1985, Stein became increasingly concerned about Thatcher’s intentions. I was part of a BBC Scotland TV team which made a TV documentary series about Scottish football in 1985 and which had unprecedented access to Stein in his last months. In conversation, he returned repeatedly to his suspicion that not only did the Prime Minister harbour malign intentions towards football but that it would gratify her if Scottish fans caused trouble in Cardiff, so that England would not be alone in purdah.

I have related some of my experience of his last days previously in the Telegraph, notably when he granted me his final interview six hours before he died. Sir Alex unfolded another graphic chapter at Hampden on Monday evening when he told how Stein was sitting at the front of the Scotland team bus when it was returning to the training base in Ayrshire during the miners’ strike.

Bear in mind that Stein is the man who once said: “You go down that pit shaft, a mile underground. You can’t see a thing. The guy next to you, you don’t know who he is. Yet he is the best friend you will ever have.”

The bus overtook a convoy of lorries bearing coal into the county, which was NUM territory. Stein, fulminating about “scab miners”, ordered the Scotland coach driver to stop, got off, stood in the middle of the road and flagged down the lead trucks, imploring them to turn back. Faced with the Scotland manager in incomparably impassioned mood, they complied, although what they did when he was safely out of sight is another matter.

By the time of Scotland’s encounter with Wales, Stein was so concerned about the possible consequences of fan disruption that he confessed to sleepless nights beyond the range of his customary deprivation as an insomniac – a condition not allayed by his teetotalism. He had also been on medication to allay cardiac stress from the night that Wales had beaten Scotland at Hampden Park with a Mark Hughes goal in the first qualifier between the sides.

In the event, although Welsh fans were entitled to dispute the penalty award which saw Davie Cooper secure the draw which propelled Scotland into the 1986 World Cup finals, the occasion passed peacefully. Just as Stein’s fears of political meddling were allayed, he suffered his fatal collapse.

Stein died at the juncture of the old football world and the new and at the crossover from the industrial age to the IT era. Heysel, Bradford and then Hillsborough triggered stadium reconstruction on a colossal scale, the Bosman rule unleashed unstoppable wage inflation and satellite broadcasters jostled to pay the bills.

It has been asked if Stein could have coped with the new breed of footballers who control their own intellectual property rights and trail their opinions across social media. The more pertinent question, surely, is – how many of today’s managers, if transported back in time, could have emerged from the Lanarkshire coalfield, won the European Cup with a bunch of local lads and accumulated 25 domestic honours at a time when Scottish clubs were an acknowledged force outside their own realm? That is the enduring legacy that will be commemorated this morning when the surviving Lisbon Lions join with Stein’s family for a ceremony at the statue of the manager which stands outside Celtic Park. He was known as the Big Man. His shadow has not shortened with the years.

Jock Stein to have full control over Celtic players

http://www.scotsman.com/sport/football/spfl/jock-stein-to-have-full-control-over-celtic-players-1-3724628

From The Scotsman, 13 February 196

2 comments

Have your say

Jimmy McGrory is put into a PR post, reports John Rafferty

From The Scotsman, 13 February 1965

JOCK Stein has resigned from his post as manager of the Hibernian Football Club to become manager of Celtic. Sean Fallon, the Celtic coach, is to be his assistant manager and the present manager, Jimmy McGrory, is to be Public Relations Officer. That is the effect of a modernisation of the management side of the Celtic Football Club which was announced yesterday.

The action started with a midday announcement by Mr W.P. Harrower, chairman of Hibs, of Jock Stein’s resignation.

Mr Harrower and the past chairman, Mr Harry Swan, had no need to elaborate on the loss to the club or on the magnificent job that Jock Stein had done in the ten months that he has been with the club. The record is clear. he took them from utter depression to win the Summer Cup and now to be virtual top of the First Division of the Scottish League. That needs no elaboration.

Mr Harrower spoke of the pleasantness of the parting, regrettable though it was, and that there were no strained relations between the people concerned. It was a very adult operation. Jock Stein had no contract with Hibs and he will have none with Celtic.

In Glasgow in mid-afternoon, Mr Bob Kelly, chairman of the Celtic Football Club, spoke for his board. He spoke of how Celtic were concerned about the whole trend of modern football and of how clubs now had to think more about management. His opinion was that at present managers had too much to do.

He said the club now need a public relations officer and that his duties would be many and varied, stretching from the dissemination of news to investigating the potential and the background of players the club might be interested in.

In appointing Jimmy McGrory to that post they thought that they had the ideal man for there was no better-liked man in the game. He was a well respected world figure. Jimmy McGrory’s appointment was permanent, to last as long as he lived, and that is a wonderful gesture to a great servant who has been with the club, except for one brief break, since he was signed as a player from St Roch’s in 1921. Mr Kelly’s final words were: “No matter where he travels, we are sure he will bring nothing but respect and dignity to the club.”

Mr Kelly said that as soon as his board had decided to make a change, Jock Stein was obviously the man to approach. He had known him as a boy in his own town of Blantyre and knew him with Celtic as a player and a coach.

He had left Celtic because like everybody else, he had to learn his trade, but there had always been an understanding that he would return to Celtic. This he has now done.

Sean Fallon has been appointed assistant manager, but any appointments below that level are being left for the new manager, who will be given full control of the Celtic playing strength.

Jock Stein is only Celtic’s fourth manager since the institution of the club in 1888. Willie Maley was manager for 50 years, and then there was a brief spell in which Jimmy McStay served before Jimmy McGrory was appointed in 1946.

Jock Stein started as a centre-half with Albion Rovers in 1942, and then was rescued from the depths of non-league football when Celtic unexpectedly signed him. His fortunes have never looked back since that day, but one cannot help thinking that he might have been lost to football had Mr Kelly not remembered him playing about Blantyre, and had the courage to bring him back.

He has since put Dunfermline on their feet, and has done the same with Hibs, and now he takes over Celtic, who are in a much less desperate plight than either of these two clubs. It is a shattering blow for Hibs to lose him, but it is a wonderful stroke of business for Celtic, and nothing more exciting could have been thought up for their supporters.

Hibs now have the tough job of finding a new manager. There are two obvious men in mind, but it would be unfair to speculate for they are managing other clubs. Jock Stein will be hard to replace, but at least the new man is taking over a successful going concern.

Then Hibs manager Jock Stein chats with Easter Road club chairman Willie Harrower after a board meeting in March 1964. Picture: TSPL

Sir Alex Ferguson on the Lisbon Lions and the 50th anniversary of Celtic’s most famous night: ‘What Jock Stein achieved will never be done again’

• Jock Stein took Sir Alex Ferguson on has his No 2 when manager of Scotland

• Ferguson was at a celebration of Stein’s famous Lisbon Lions squad in Glasgow

• The Scot believes what his old mentor achieved will never be replicated again

By Hugh Macdonald For The Daily Mail

Published: 22:30, 26 May 2017 | Updated: 01:57, 27 May 2017

If you could listen in to one conversation about football, a seat at the table with Sir Alex Ferguson talking about his great friend and mentor Jock Stein would be the place to be.

Imagine being given the opportunity to hear the secrets of the mighty Lisbon Lions, 50 years after the team packed with local Celtic boys defeated Inter Milan 2-1 to win the first European Cup for a British team. Not to mention how such glory inspired Ferguson to win trophies galore of his own in the years that followed.

Ferguson and Stein, two brilliant and remarkable Scotsmen, worked together for the national side — Stein as the studious manager, Ferguson as his fledgling No 2. You can hear the respect when Sir Alex recalls those days.

The former Manchester United boss was in Glasgow at the Celebrate ’67 event on Thursday

‘The great value was in the Saturday nights we met in the hotel at home or when we were abroad,’ says Ferguson of his duties as assistant to Stein during Scotland’s qualifying campaign for the 1986 World Cup. ‘It was fantastic. He was not a great sleeper so he would have you still up at three or four in the morning with (masseur) Jimmy Steele making pots of tea.

‘I would say to him, “Jock, we need to get into our beds now. I am taking training in the morning”. He would reply, “You will be all right, son. You will get a sleep in the afternoon. Steely! Get another pot of tea on”.

‘He was one of the greatest managers of all time. Without question. He did something that has not been done before and will not be done again. You cannot overstate that. This is what makes him unique.

‘It is what Alexander Fleming did when he discovered penicillin in a wee laboratory. It is what Alan Turing did when cracking the Enigma code. That is one standard of greatness and Jock met it.

+‘The Lisbon Lions were brought up within 30 miles of Celtic Park. That was never done before Jock. It will never be done again.’

The relationship had been forged some years earlier in meetings at the Beechwood restaurant in the south side of Glasgow.

Ferguson and his wife Cathy lived in Simshill and would go to the local restaurant where Jock and Jean Stein and Sean Fallon, assistant manager at Celtic, and his wife Myra had a regular Saturday evening dinner date.

‘Inevitably, I would get a table beside them,’ says Ferguson. ‘It was great to have a chat with him but, remember, I was a player then and I would never at that stage be too forward.

‘I would never ask how his game went that day or anything like that. I would never be that familiar. You were not at the level to ask such questions. He was a top manager at Celtic and I was a player at Rangers, totally different stations in life. But he was always really good to me.’

As the friendship deepened, Stein and Ferguson talked every week on the phone. It was no surprise that Ferguson invited the manager who won the European Cup in 1967 to Gothenburg, where Aberdeen would defeat Real Madrid in the European Cup- Winners’ Cup final in 1983.

‘He was brilliant, never intrusive or overbearing. He told me, “I am not going to get in your road. Get on with your business. If you need me, you know where I am”.’

Ferguson acted on two pieces of advice from Stein. ‘He told me to make sure we took the second training session at the stadium on the night before the game,’ recalls Ferguson. ‘Jock said that Alfredo di Stefano, the Real manager, would think we would have watched his session and might be unsettled by that.

‘Jock also bought a bottle of, I think, Black Label and he told me, “Give that to Di Stefano as he comes off the pitch after the training session”. I said, “Why?” Jock replied, “He will think you are a wee guy from Aberdeen, that you are dancing to his tune, lying at his feet”. I gave him the bottle of whisky and he did not know what to say to me. It was a sort of mumbled “Gracias, gracias”. I caught him on the back foot.

‘It may have gave him the impression that we were a wee club from Aberdeen and we had no right to be playing Real Madrid, that we were just grateful to be there.’

He adds: ‘It seems like a superficial thing, but it was profound. Clever.’ Aberdeen won 2-1.

Soon Ferguson and Stein were working for Scotland in the successful campaign to qualify for the 1986 World Cup, although he admitted he felt ‘apprehensive’ about working with someone of Stein’s stature.

‘You are working with someone who has won the European Cup, nine championships in a row. But I was starting to do well at Aberdeen. When he offered me the job I jumped at it. It was a boost for me at that time in my career. I was basically learning all the time and keen to do so. It was an honour first of all. But what an opportunity, the chance to learn from someone like Jock Stein.

‘To be honest with you, I bombarded him with a million questions every time I was in his company. It was just football, football, football.

‘But I learned, too, about the power of information. He was a great networker, knew everything that was going on. He used to phone me on a Saturday night and tell me all that was happening in the game.

‘He was sharp. He would tell me on Scotland duty that such and such a club official would be phoning in later to tell him that certain players had pulled out. And it would happen. He was always prepared for it.’

What did the young Ferguson provide for Stein? ‘My energy was important,’ says Ferguson, now 75 but in his forties when working with Stein. ‘He had health problems and he maybe saw me as a driver on the training field.

‘I remember when he was offering me the job he told me I would do the training. I said, “What about picking the team?” And he replied, “Aw no, son, that is my department. I will discuss it with you. You will be helpful in that area and don’t be afraid to give your opinion, but that is my job”.’

Ferguson learned another lesson that has accompanied him through life. ‘There was a great level of trust in me. There was respect,’ he says. ‘I appreciated that. I have learned that when you pick an assistant the first thing, the most important thing, you need to look at is, “Can I trust this man?” He got trust from me. I idolised him.’

Stein, he says, was a man of ‘extraordinary intelligence’, adding: ‘He made it his business to find out everything. I was working with him with Scotland and he asked me to accompany him to the press conference. I told him I was taking one of the players to the gym. He said, “No, come to the press conference, you will learn something”.’

Ferguson adds with a chuckle: ‘Sitting outside the press conference, he would tell you something about each and every journalist: who liked the bookies too much or the drink or women, or whatever. He knew everything about them.’

This knowledge stretched into every area. ‘You knew he knew everything,’ says Ferguson. ‘So when I became a manager I would tell him everything. You were frightened he would catch you out.

‘He would phone me every weekend. I would say something like, “I have made a bid for Billy Stark”. He would say, “Oh, that’s a good move, he will be a good signing for you, I like him myself”. Or I would tell him I thought one of my players was ready to leave and he asked me what I was thinking about in terms of replacing him, and would ask, “What are you thinking about and have you thought of this or that?”’

Ferguson transformed all the clubs he worked for but his major impact was, of course, with Aberdeen and Manchester United — where he won a glut of European and domestic trophies.

‘I always believe I should address matters straight after the game,’ says Ferguson. ‘But Jock was different. He always said it was better to leave it to the Monday, when everyone had calmed down a bit. He said, “You will have a clear mind yourself and that helps”. He was right for most people but that was not my nature. My nature was to get it all out the road and start afresh the next day.

‘His advice was great to hear but he was very understanding of my character, too. He understood that people would like to do things their way and he would help individuals match their character to a good way of working,’ explains Ferguson, who recalled Stein’s immediate and dramatic impact at Celtic.

‘The size of the revolution was incredible. He took over a Celtic team in 1965 who were far from world-beaters. Two years later — with the addition of Willie Wallace and Joe McBride — he took them to the European Cup final and victory against a very good Inter Milan.

‘Think about it. It is astonishing. How did he do that in terms of changing not only personalities of the players but the very character of a team?

‘He recognised greatness when others could not. He saw potential when others missed it. For example, I played against Bobby Murdoch in reserve matches in the early 1960s and he was an outside right. All of a sudden he is playing centre midfield. He was the fulcrum for Celtic, hitting those long, diagonal passes or the short incisive pass or striking from outside.

‘I think Celtic had two world-class players who would have graced any team at any time. One was Bobby, the other was Jimmy Johnstone.

The event at the SSE Hydro on Thursday was attended by a host of fans, and former managers

‘Bertie Auld was nearly in that class, too. The rest were very, very good players but Jock transformed them into perennial winners.

‘Big Billy and John Clark were not the quickest but they never got caught out. They dropped off, never leaving space behind. Billy would win everything in the air, John would pick up second balls and cut off space. It was simple but very, very clever.

‘He basically always played with two wide. This left the opposition with a dilemma. In the cup final of 1965 I remember thinking, “Do we push our full backs right on top against their wingers?” ’

His overwhelming sense is that he was blessed to have known Stein. ‘Every Celtic fan will have that sense of gratitude. It was an incredibly exciting ride for the club. And don’t I know it. I had to suffer it for some time as a Rangers player.’

![[Untitled] [Untitled]](https://wikifoundryimages.s3.amazonaws.com/5c2c93d5fcb83f31b3da84fd31815860)

![[Untitled] [Untitled]](https://wikifoundryimages.s3.amazonaws.com/1275f1a21dba3be2357685b65e43b0a3)