| Back to Player Homepage |

JIMMY JOHNSTONE – A TRIBUTE TO A CELTIC LEGEND

By David Potter

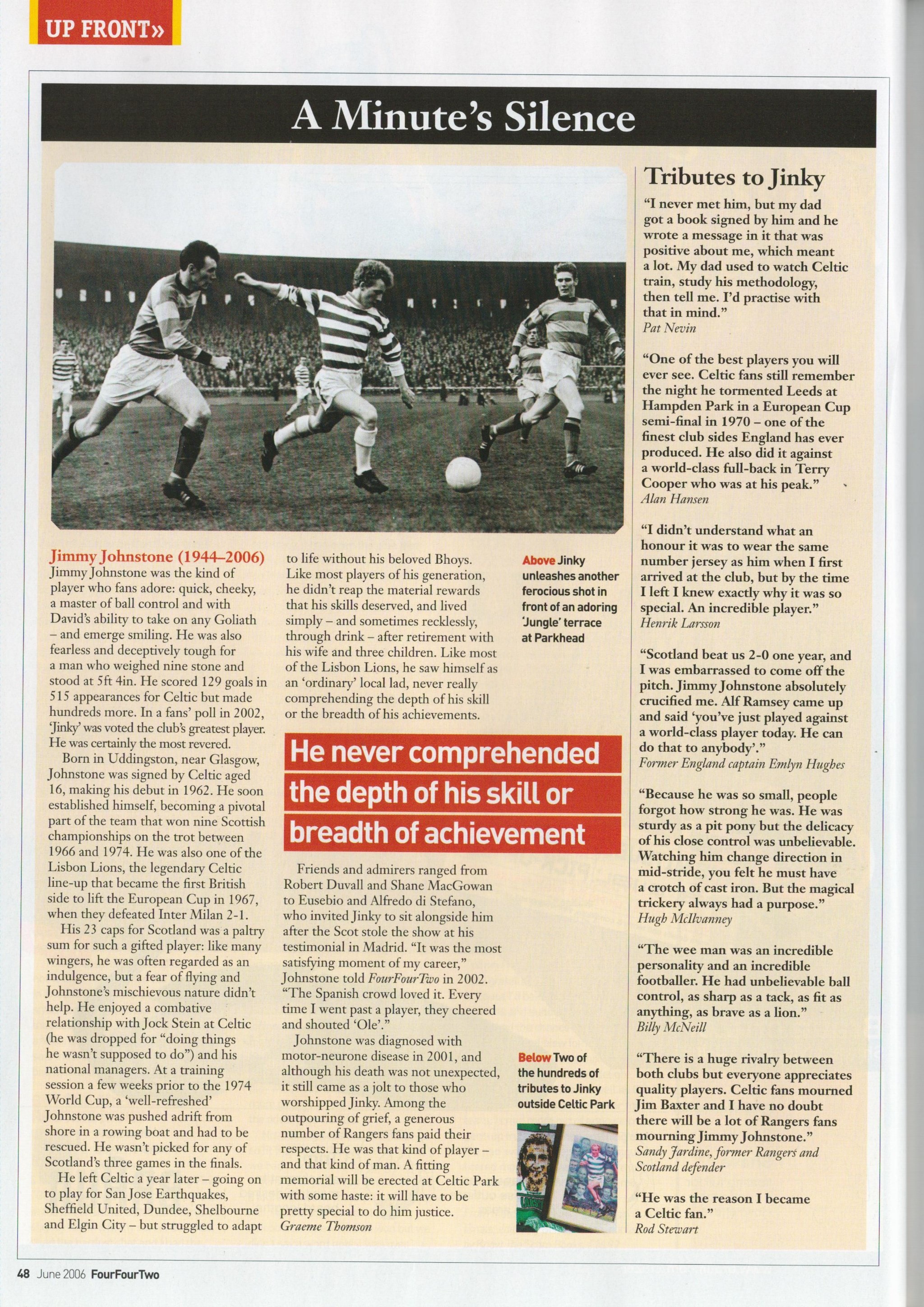

The majority of Celtic fans agree that Jimmy Johnstone was Celtic’s greatest ever player. Certainly those who saw him in his prime will find it hard to dispute the contention that he was a very talented natural ball player with tremendous skills of trickery, ball control and the ability to beat man after man. Well, was he worth the nickname “Jinky”?

Jimmy was born in Viewpark, near Uddingston in 1944. He was of a very Celtic-minded family and by 1958 he had become a ballboy at Celtic Park, before joining them as a player in November 1961. By this time he had practised his skills as a player, having read about the great Stanley Matthews of Blackpool and England, and anyone who had seen him in training or in junior matches would be consistently impressed by this redhead.

The problem was that he seemed to have come at the wrong time. The era of the dribbler had gone, and even the role of the winger was now in question with team formations like 4-2-4 becoming more common. The days of the Jimmy Delaney style of charging down to the by-line and crossing, or cutting inside to devastating effect seemed to have gone. But Jimmy was good enough to be given a chance.

Jimmy’s debut was an appalling 0-6 defeat by Kilmarnock on March 27th 1963, a defeat which, though severe, was not entirely unexpected in the crazy days of 1963. A far more significant day was the Scottish Cup Final of May 4th against Rangers in which the miniscule redhead was a success and on several occasions seemed capable, with a little more support and encouragement, of winning the day for Celtic. After all that, he was dropped for the Replay and disaster ensued.

By 1964, Jimmy was playing well for Celtic in their partial recovery of the early part of the year, but by the time that Jock Stein arrived in January 1965, he was out of favour. This was due not least to a nasty incident at Ibrox on New Year’s Day when Jimmy, mercilessly and repeatedly fouled by Rangers’ Tottie Beck, retaliated and was sent off. Jimmy did make a good job of the retaliation, but Beck was not as badly injured as he appeared, recovering as soon as Jimmy disappeared up the tunnel.

This highlighted an aspect of Jimmy’s character – his occasional lack of self control, something that only improved with age, as he grew older and wiser. But as one of his team-mates put it, “Jimmy wisnae daft. He just did daft things”, and although no-one could say that the relationship between Jimmy Johnstone and Jock Stein was a smooth one, Jock eventually got the best out of Jimmy and Jimmy grew to see in Jock a father figure whom he could respect and admire. It took time though.

Stein was still Manager of Hibs when Jimmy was playing in a reserve match at Parkhead. By chance they met in the toilet. Jock expressed surprise that Jimmy was playing in the reserves. “You’re far too good a player for that,” Jock growled, and Jimmy then realised that there was somebody (and a very important somebody) who rated him.

European adventures posed a particular problem for Jimmy, for he suffered dreadfully from a fear of flying. Such a condition is of course far from unusual – in fact it is almost universal, but if you are one of the best footballers on earth, your neurotic wheengings tend to be taken a little more seriously. Stein could turn this to Celtic’s advantage, and on one occasion said that Jimmy would be exempt from a trip to Belgrade if Celtic had a substantial lead from the First Leg of a European Cup tie. Jimmy inspired Celtic to take a 5-1 lead, and he stayed at home as the team drew 1-1 in Yugoslavia.

It was abroad that Jimmy was most revered. The sight of a diminutive redhead who could dribble was of course an unusual tourist attraction in Europe, and Jock employed him for example in the European Cup Final of 1967 to dribble with the ball in the early stages in order to win over Portuguese opinion. By the end of the first 15 minutes, the Portuguese were cheering on Celtic.

Johnstone was always good copy for the newspapers who realised his importance to the Celtic side, and they played up his foibles. His fear of flying was made a big issue, a Church once wanted to have him in a stained glass window, he once withdrew from a Scotland squad and a picture was taken of him lying in bed with a doctor’s sick note, lest we thought he was faking it. He loved singing and palled about with Bobby Lennox, the two likely lads being seen one day getting off the train before a game in Aberdeen, arms round each other singing “Roll Over, Beethoven”.

He may have been afraid of an aeroplane, but one thing that he did not lack was courage when facing some of the brutal Spanish or Argentinian defenders that he met. His courage lay in his determination to come back after having been downed, knowing that he might be downed again. Sometimes he would beat the defender, then could not resist beating him again. The crowd loved all that. Once at Aberdeen, all of Pittodrie howled not so much in anguish as in mirth at the sight of the Aberdeen full back lying helplessly on the ground and having nothing else to do but the grab Jimmy’s leg as he ran away from him!

Indeed, there was no greater sight than Jimmy charging down the right wing following a through ball from Murdoch. There was always the feeling that something was about to happen. Sometimes it did, other times there was a disappointment, but the potential was always there.

Jimmy was loved particularly by the Celtic fans, who recognised him as one of their own. It was an age where the stereotype of the wee cheeky Glasgow boy had not yet disappeared. Add the very Celtic touch of the red hair, and we have the very epitome of the Glasgow Irishman. This was why he could be nothing other than Jimmy Johnstone of Celtic. Occasionally Scotland perhaps, but Celtic through and through.

Jinky was one of the few players (Lennox and McNeill being the others) who stayed the course of all nine League titles in a row between 1966 and 1974, and it is his trickery which symbolised a generation of Celtic. He had many outstanding games, particularly against Rangers, and scored a large total of 129 goals, a surprising amount of them with his head.

Jimmy was less successful for Scotland, but scored two fine goals against England in 1966, which gave Scotland a chance in a game that they eventually lost 3-4. But his best Scotland game was that of 1974 (in the immediate aftermath of his boating incident at Largs) in which he played brilliantly in Scotland’s 2-0 victory. Many people believe that Scotland might have won the crucial game against Yugoslavia in the 1974 World Cup, had Willie Ormond brought Jimmy on at half-time. He won 23 caps.

He eventually left Parkhead in 1975, and went on his travels elsewhere, at one point teaming up with old team-mate Tommy Gemmell at Dundee, but he was never a success. He was too much of a one-team man, and even during his sad illness, could be seen now and again at Parkhead cheering on his beloved Celtic.

Jimmy was totally unpretentious, retained his sense of humour, and in spite of the common perception that he had made enemies at Rangers having bested them so often, Jimmy remained on good terms with Rangers players that he played against.

At one point, after he gave up football, he was working in the construction industry on a project on Kirkcaldy beach. Where did he go for his lunch? Well, where else than to the pub of Willie Johnston (ex-Rangers) where they swapped stories about old times!

In his later years with the dreadful Motor Neurone Disease, Jimmy faced the inevitable with a quiet dignity and was proud to be associated with a charity for this awful disease. Not only was this in keeping with the proud traditions of the Club which he served, but it was also typical of the man.

When Jimmy Johnstone died on March 13th 2006, there was a collective intake of breath from Celtic supporters everywhere – but not only Celtic Supporters. Rangers and England Supporters, whose defences he had terrorised, still retained a soft spot for Jimmy.

We will certainly never see his like again. We will miss him.

Hail! Hail! Jimmy Johnstone, the Greatest Ever Celtic Player!

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Entry

Johnstone, James Connelly[Jimmy, Jinky](1944–2006),footballer, was born on 30 September 1944 at 647 Old Edinburgh Road, Viewpark, Lanarkshire, the youngest of five surviving children (three had died in infancy) of Matthew (Matt) Johnstone, coalminer, and his wife, Sarah,née Crawley. He had an elder brother, Patrick, and three elder sisters, Theresa, Ann, and Mary. He was educated at St Columba’s Roman Catholic primary school in Viewpark and St John’s Roman Catholic secondary school in Uddingston. He became a Celtic ‘ball boy’ aged thirteen before playing for the club he, his family, and most of his local Catholic community of mainly Irish extraction supported. On leaving school aged fifteen he worked at Glasgow’s meat market, then acquired a job in a clothing factory, and subsequently began an apprenticeship as a welder. From the latter two jobs he travelled two evenings a week to train with Celtic, the club for which he had recently signed, despite the close interest of the Manchester United manager Matt Busby. The red-haired Johnstone was later farmed out to a local junior club, Blantyre Celtic, for experience, and to add to his 5 feet 2 inch, six stone frame. He eventually settled at 5 feet 4 inches and weighed under ten stone throughout his playing days. On 11 June 1966 he married Agnes Docherty, a nineteen-year-old coil winder from Uddingston, and daughter of John Docherty, joiner. They had three children, James, Marie, and Eileen.

Johnstone had made his début for Celtic in March 1963 but only began to thrive and fully develop with the arrival of Jock Stein as manager in 1965. Johnstone went on to play 515 times for Celtic, scoring 129 goals. Although renowned as a small ‘jinking’ winger who mesmerized his opponents by dribbling the ball by and around them (sometimes repeatedly), he was an exceptionally rounded footballer. He was an outstanding passer of the ball and had dynamic speed, superb control, and exceptional spatial awareness. Despite his diminutive size a number of his goals were scored with his head. Although a brilliant individual, he was also a team player.

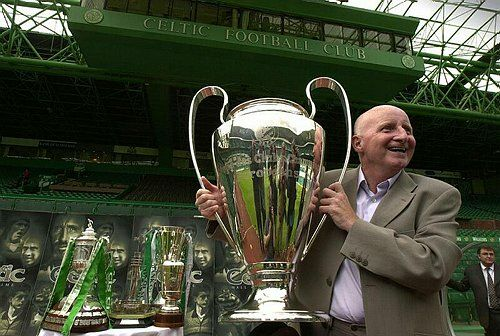

Between 1965 and 1974 Celtic won a then world record nine consecutive national league titles and numerous other trophies. In those years the team also played in four European champions cup semi-finals and two finals. In 1967 Celtic’s ‘Lisbon lions’ became the first northern European club to win the European champions cup, beating Inter Milan 2–1 in the Portuguese city of Lisbon. Celtic again reached the final in 1970, but lost to Feyenoord. Johnstone was an outstanding member of the Celtic team during this period: a team that remains Scotland’s most successful in European football. In the year Celtic won Europe’s most prestigious football trophy Johnstone finished third in the voting for the European footballer of the year.

Johnstone made his full international début in 1964. He went on to play twenty-three times for Scotland. Among the reasons for such a small number of international caps (given his exceptional talent) were his fear of flying abroad for games, his occasional disciplinary problems (sometimes striking back at the brutal play of less skilful opponents), and a poor relationship with the Scottish football authorities, who were certainly affected by the anti-Catholic, anti-Irish, and anti-Celtic prejudices then prevalent in Scottish football and society. These manifested themselves in the way Johnstone was sometimes booed by home fans while playing for Scotland in Glasgow. The booing was compounded by the massive presence of Glasgow Rangers supporters among the Scotland fans, many of whom also preferred Willie Henderson, the Rangers winger.

On the field Johnstone was not inhibited by his lack of height and weight. In years of ball work and practice he had honed skills that were often beyond taller and more athletic looking footballers. As a youngster, after readingFeet First(1948), Stanley Matthews’s autobiography, he had taken to dribbling around milk bottles every day in his hallway for three hours to perfect his skills. These were matched by a good deal of bravery, which was often required as ‘Jinky’ was frequently booted by less skilful players.

Johnstone’s fear of flying was so intense that in November 1968 he arranged with the manager, Jock Stein, that he would be spared the flight to Yugoslavia for the return match of a European cup tie against Red Star Belgrade if he helped Celtic acquire a three-goal lead from the first match in Glasgow. Johnstone duly tore one of Europe’s leading teams apart, scoring twice and laying on three other goals in a 5–1 victory: he didn’t travel to the away tie. Johnstone said about Jock Stein, ‘Jock was good with tactics, but his real talent was with people … He knew if you had a problem’ (The Independent, 14 March 2006). Johnstone was uncomfortable with fame and ended up too often in bars. Stein used his network of Celtic-supporting informants to let him know whenever Johnstone was out drinking, and Johnstone would often receive a reprimanding call at the pub from Stein. Stein said:

people might say I will be best remembered for being in charge of the first British club to win the European Cup or leading Celtic to nine league championships in a row, but I would like to be remembered for keeping the wee man, Jimmy Johnstone, in the game five years longer than he might have been. That is my greatest achievement. (Daily Telegraph, 14 March 2006)

Johnstone was eventually let go by Celtic in 1975. Thereafter he played briefly for San Jose Earthquakes, Sheffield United, Shelbourne, and Elgin City, before finishing his playing days back at Blantyre Celtic. He also briefly returned to Celtic Park in the mid-1980s to coach youth players. He had made no plans when he finished playing football and soon found himself in considerable difficulties—drinking too much, working as a navvy, and piling up debts. But the love of his family, his strong religious faith, and his infectious personality and sense of humour pulled him through those dark days. In Johnstone’s latter years the actor Robert Duvall, who consulted him when making a football film, declared ‘Wee Jinky Johnstone’ the most remarkable character that he, in a lifetime in Hollywood, had ever come across. In a similar recognition, in 2005 Johnstone was immortalized on a limited-edition Fabergé egg, the only living person since the tsars and tsarinas of Russia to have been honoured in that way.

Celtic continued to be Johnstone’s passion long after he stopped playing and he could often be seen at Celtic Park as a match-day host until he was diagnosed with motor neurone disease in 2001. To raise funds for the Motor Neurone Disease Association, together with Jim Kerr of the pop group Simple Minds, he launched a new version of the classic song ‘Dirty Old Town’, also a Celtic supporters’ favourite. ‘Jimmy was among the greatest players this game has seen’, said Billy McNeill, the former Celtic captain. ‘However, I have as much respect for him as a man and the courageous way in which he handled his illness as I have for him as a footballer’ (The Independent, 14 March 2006). In 2002 Johnstone was voted Celtic’s greatest ever player. A statue of him was unveiled outside Celtic Park in December 2008.

Johnstone died on 13 March 2006 at his home in Mossgiel Gardens, Uddingston, only a few hundred yards from where he was born. His funeral mass was held on St Patrick’s day 2006 at St John the Baptist Church in Uddingston, concelebrated by numerous priests led by the bishop of Motherwell, Joseph Devine; thousands attended as his funeral cortège passed by. He was buried in Bothwell Park cemetery, near Uddingston. He was survived by his wife and children.

Joseph M. Bradley

Sources

J. Johnstone,Fire in my boots(1969) · T. Campbell and P. Woods,The glory and the dream: the history of Celtic F.C., 1887–1986(1986) · J. M. Bradley,Celtic minded: essays on religion, politics, society, identity and football(2004) ·Evening Times[Glasgow] (13 March 2006); (14 March 2006); (18 March 2006) ·The Herald[Glasgow] (14 March 2006); (15 March 2006); (17 March 2006); (18 March 2006) ·Daily Record(14 March 2006); (16 March 2006); (18 March 2006) ·The Times(14 March 2006); (24 March 2006) ·Daily Telegraph(14 March 2006) ·The Guardian(14 March 2006) ·The Independent(14 March 2006) ·The Scotsman(15 March 2006); (18 March 2006) ·Sunday Times(19 March 2006)Likenesses: photographs, 1960–2003, Camera Press, London · photographs, 1963–2004, PA Photos, London · B. Thomas, photograph, 1964, Getty Images, London, Bob Thomas Sports · photograph, 1967, Hult. Arch., London · photographs, 1967–74, Photoshot, London · M. l’Anson, mixed media on paper, 2003· statue, 2008, Kerrydale Street, Glasgow · obituary photographs · photographs, Rex Features, London · photographs, repro. in Johnstone,Boots·

Joseph M. Bradley, ‘Johnstone, James Connelly(1944–2006)’,Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Jan 2010 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/97085, accessed28 June 2011]James Connelly Johnstone (1944–2006): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/97085

LISBON LION STILL FIRES IMAGINATION

Hugh McIlvaney

With the desperate fight against motor neurone disease remorselessly reducing his mobility, Jimmy Johnstone won’t be able to travel down from the west of Scotland on Tuesday for a little ceremony in his honour at the House of Commons. But he will be a lively presence in the minds of the gathering, for Johnstone is one of those rare footballers who brighten indelibly the memories of everybody who witnessed them at work.

Of all the boys of winter who have lifted my spirits over many decades, none has left more vivid images than the wee man, and not just because he was the most magically intricate dribbler I ever saw.

It was his capcity to express effervescent, outrageous almost surreal mischief through his play – and to make ll of his darting runs and surges of convoluted trickery a deadly weaopon for his team – that rendered him unforgettable. That and the ability not only to thrill but, with his antics on the field, to evoke smiles and sometimes laughter.

At the Commons, there is to be an unveiling of an egg, but no ordinary egg. It is the first of a series of 19 that will be created by Sarah Faberge, great-granddaughter of Carl Faberge, the Russian royal court jeweller. The total of 19 corresponds witht he number of major winner’s medals amassed by Johnstone (including his precious souvenir from 1967, when Celtic’s Lisbon Lions became the first British team to capture the European Cup).

From the sale of the egggs, he will be helped financily in the battle with his affliction. Sarah Faberge was moved by the bravery of that struggle and says he is the first living person since the Czars and Czarinas to have a Faberge egg designed in his honour. Watching him as a player on film, she was entranced by the wonders he performed. That puts the lady in a rather substantial throng.

below from 4-4-2 magazine