| J | Player Pics | World War One | A-Z of Players |

Personal

Fullname: Peter Johnstone

Born: 30 Dec 1887

Died: 12-16 May 1917 (killed in battle)

Birthplace: Cowdenbeath

Signed: 9 Jan 1908

Left: 11 Mar 1916 (attested)

Position: Defender/Midfield

Debut: St Mirren 1-0 Celtic, League, 3 April 1909

Internationals: Scotland/Scottish League

International Caps: 0/1

International Goals: 0/0

*Date of Birth & birthplace corrected using research from Celtic history reserachers.

Biog

Coal miner Peter Johnstone signed for the Bhoys in January 1908 from Glengraig Celtic and for the best part of the next decade the Fifer was to be an invaluable asset to the Parkhead side before the horrors of war claimed his young life.

He arrived from Fife and was a miner in Glencraig prior to Celtic. The tall and fair-haired Johnstone was a pre-war Celtic favourite who played for Celtic 223 times and was one of the players who helped Celtic on the road to win 6 league titles in a row under manager Willie Maley.

Blessed with the talent and intelligence to adapt to almost any position Peter Johnstone turned out at inside-left, left-half and centre-half. It was in the latter position that Peter Johnstone truly excelled, although as a left-half he was more than capable of contributing with regular goals. He was also a great supplier of goals for fellow minder Jimmy Quinn.

He was idolised by the Celtic support, and it was said:

“Celtic fans idolise Peter Johnstone… a lion’s courage… has played in almost every position… never let the side down“.

He won a Glasgow Cup medal & Scottish Cup medal in his first season, and helped push the side to win a Scottish Cup in 1911/12 in a 2-0 win over Clyde at Ibrox.

He was converted from the front line to the centre-half role, following in the footsteps of Willie Loney and provided the Bhoys was sterling and solid service at the very heart of a robust and resilient Celtic defence.

Taking over this centre-half position for season 1913/14, the club won its third league/cup double. Johnstone took over this role with relish, and in the defensive unit of Young/Johnstone/McMaster they give little away (only 14 league goals lost all season). Johnstone actuallly humoured about the change to centre-half saying: “The softest job I’ve had all season“.

Peter Johnstone was part of the infamous side who contested for the ‘missing‘ Ferencvaros Cup in Budapest against Burnley in 1914. The game ended in a draw and it was reluctantly agreed that a return would be played in Burnley. Celtic won and the trophy never materialised. Apparently he had a sharp temper, and had to be restrained from taking on Burnley’s yappy Ulsterman Jimmy Lindley.

As a measure of his value, he was awarded a cap for the Scottish League select in a 2-1 win over the Irish League select played in Belfast on 18 November 1914. Played with three other Celts and three Hearts players.

The war years put a halt to ambitions, but he still played for Celtic (although apparently a little more filled out). Continued being a courageous performer he helped the title winning Hoops of 1915 and 1916 [while combining his role as a footballer with that of a miner doing his shift (he had to return to the mines for the war effort) *this bit needs confirmed if true that he worked in the mines during the war].

On 11 March 1916 Peter Johnstone signed up to join the troops on the frontline and in May that year was called up by the 14th Battalion of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders.

Football was in the blood, and he travelled overnight by train from the South of England to play for Celtic to knock out Rangers from the Glasgow Cup in Sep 1916. He would play his last game for Celtic on October 7th 1916 earning himself another winners medal as the Bhoys defeated Clyde 3-2 in the Glasgow Cup final.

He later transferred to the 6th Battalion to get to the front line faster in France, but just seven months later – on around May 12th-16th 1917 – Private 285250 Peter Johnstone would be killed in action. Peter Johnstone had been transferred to the Seaforth Highlanders who happened to be at the Front, he didn’t ask to go to the Front. He was one of thousands of young men to fall at the Battle of Arras, northern France. His body was laid in an unmarked grave, and ex-Celt Joe Cassidy looked for his grave. Peter Johnstone left behind a wife and two children who were joined in their grief by thousands of Celtic fans.

A dedication to his memory is inscribed on Bay 8 of the Arras Memorial in the Fauborg d’Amiens Cemetery (Below).

Peter Johnstone is an all-time Celtic great, and at the time of his passing his loss will have been keenly felt across Scotland. His memory lives for evermore.

“A loyal servant you have been

Long may you wear the hoops of gren

Your well-kent of old be seen

On our own Paradise. No warmer Celtic heart than thine

Long may your star ascendant shine

Full sure when Celtic made you sign

They booked a prize.”

In Memoriam on 23 May 2015, in memory of Peter Johnstone, a remembrance service was held in respect to him organised by the ‘Peter Johnstone Memorial Group‘. Funds were raised to build a lasting memorial, comprising a wonderful statue and surrounding gardens. Much respect to all for this fitting tribute.

Playing Career

| APPEARANCES |

LEAGUE | SCOTTISH CUP | LEAGUE CUP | EUROPE | TOTAL |

| 1908-17 | 211 | 22 | n/a | n/a | 233 |

| Goals | 17 | 2 | – | – | 19 |

Honours with Celtic

Scottish League

Scottish Cup

Glasgow Cup

- 3

Glasgow Charity Cups

- 4

Pictures

Links

Forums

Press and Articles

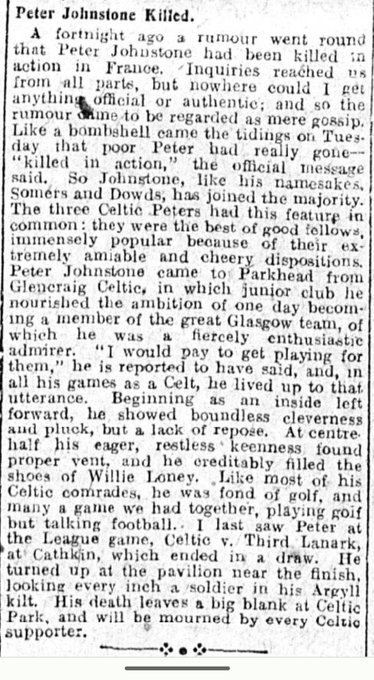

From Robert Hoskins’, Celtic Football Club and the Great War:

“Peter Johnstone who played 223 times for the club and featured prominently in the 6 league titles in a row side also died in the Battle of Arras on Wednesday 16th May. Peter joined the 6th Battalion of the Seaforth Highlanders as a Private to get quicker into the action. Peter was involved in very heavy fighting to capture a nearby chemical works between May 15th-16th. The Regimental casualty list over the 2 day Battle, reads 43 killed, 26 missing presumed dead and 51 wounded. Sadly Peter’s body was never recovered and his name is inscribed on the Arras Memorial to the Missing. Rumour of Peter’s death swept throughout Glasgow and was sadly confirmed on June 6th. His name is engraved on the Arras Memorial.”

From http://1914-1918.invisionzone.com28250 Pte Peter Johnstone 6th Bn Seaforth HighlandersPeter had enlisted in 1916, in the 14th Bn Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders (check?) but was kept in the regimental football team as he was somewhat of a football player, having starred for Celtic before the war. He transferred to the Seaforths in order to fight. [Check if he first went overseas with them…]

In Memory of Peter Johnstone 1887 – 1917

by Harrytheshadow of TheCelticWiki(2014)

Celtic stalwart, Peter Johnstone, was born in 1887 in Cowdenbeath, a small town that grew up around the many coal fields of west Fife.

The town first came to prominence in the early part of the 19th century as an important stop on the coaching route from Fife to Perth; the ‘Old Inn’ – situated at the junction of roads from Perth, North Queensferry, Burntisland and Dunfermline – being the traditional place of rest and sustenance for men, women, children and horses before making their long journey north.

By the turn of the 20th century, Cowdenbeath had become an important mining community and could claim to house the headquarters of the Fife Mining School (est. 1895) and the Fife and Kinross Miners’ Association (c. 1910). Peter Johnstone was a miner and; when it was time for young Peter to leave school; he went to the coal fields of Fife.

Evidence shows, however, that, at some point, he moved to Kirkcaldy.

I’ll soon be ringing ma Grandma’s bell,

She’ll cry, ‘Come ben, ma laddie!’

For I ken masel’ by the queer-like smell,

That the next stop’s Kirkcaddy.’

– From, ‘The Boy in the Train, by Mabel Campbell Smith.

In the verse above, from a poem first published over a century ago, the train is approaching the industrial coastal town of Kirkcaldy in Fife, where the ‘queer-like smell’ describes the reek, or stench, which stuck to the town. It emanated from Kirkcaldy’s linoleum factories which had made the ‘lang toon’ – as it is still known – world famous, but it was here that Peter made his home; at 20 Rose Street; where he lived with his wife, Isa, and their children, Nelly and Peter.

Peter had initially been identified as a forward by Celtic manager, Willie Maley. He signed for the club on the 9th January, 1908, from Glencraig Celtic – a Fife club formed by the miners of the village in 1906 after the death of Glencraig Rangers – and made his Celtic debut in April, 1909, in a 1-0 league victory against Paisley club, St. Mirren. He would go on to make 233 appearances for Celtic, scoring 19 goals in a successful footballing career, and his debut, in 1909, meant that he could legitimately lay claim to being part of the legendary six in a row side (1905-1910).

As a forward, however, Peter made little impact, but Maley saw qualities in the tall, strapping miner that convinced him that he might be able to transform him into a great centre-half: strength, determination and courage.

A new centre-half was a top priority for the Celtic manager. The Celtic side that Maley described as ‘the best team in the world’ had won a record breaking six league titles in a row from 1905 – 1910, but in 1911, Rangers were crowned champions while Celtic finished the season in 5th place. The Parkhead club was now an ageing side. Their legendary half-back line of Young, Loney and Hay had played together for the last time at the beginning of the 1910 – 1911 season and Maley knew he faced a considerable challenge in trying to replace fans’ favourite, Willie Loney, from Derry, a player who was affectionately known as ‘The Obliterator’.

But the manager was patient; he knew that, given time, Peter would develop into a fine centre-half. And he was right.

Season 1913-1914 saw Celtic regain the title along with a Scottish Cup win in April, making it a 3rd domestic double – the only Scottish team ever to have achieved the double at that time. They would go on to win four in a row (1914 – 1917), with Peter Johnstone a pivotal figure in the Celtic defence for the greater part of that campaign. Peter’s importance to the side was clearly illustrated in a Glasgow Cup match against Clyde in September, 1915, when Celtic lost 2-0 due mainly to his absence and that of fellow defender, John McMaster, both through injury.

In the same year, 1914, Celtic planned to embark on their customary tour of eastern and central Europe and Peter travelled on the club’s summer tour of Hungary, Austria and Germany, blissfully unaware that in just over two months, Britain would be at war with all three countries!

However, the tour would have been an uneventful one if it wasn’t for one match that has since been described as being, at that point in time: ‘The only contentious match involving Scottish clubs that took place on continental soil.’ – Dr Matthew L. McDowell, Associate Tutor of History at the University of Glasgow School of Humanities; ‘Scottish football, Europe, and “North Sea” cultural exchange’.

It was in the summer of 1914. Tensions in the Balkan states were already rising when, on the afternoon of 21st May, in the sweltering heat of the FTC Stadion, Budapest, Celtic lined up against English FA Cup winners, Burnley FC, to contest the strange tale of a forgotten European trophy: the Ferencevaros Cup. The shrewd organisers – directors of Hungarian club, Ferencvaros TC – had put up a trophy and had promoted the game as a ‘final’ between Europe’s two greatest sides – it was generally accepted that British teams were the benchmark across the continent at that time. This – and a guarantee that part of the gate money would go to a Hungarian charity fund – was enough to tempt Maley and the Celtic board to alter their schedule in order to take part.

It was a bad tempered match on a rock-hard surface and was played in front of 10,000 spectators; a crowd which, remarkably, was 2,000 more than the 8,000 fans who attended that year’s Hungarian Cup Final in which MTK Budapest defeated Magyar AC 4-0. In humid temperatures, Celtic and Burnley played out a 1-1 draw. Understandably, perhaps, the Hungarian organisers then quickly pressed both clubs to agree to extra-time. Celtic, allegedly, declined because they were due to return home the following day, although, some reports have suggested that both clubs refused.

Be that as it may; after much debate, both teams finally agreed to a replay in Britain with the venue to be decided on the toss of a coin – which Burnley called correctly – and, having won the toss, the English cup holders elected to contest the replay at their home ground at Turf Moor, Burnley, in Lancashire.

On 4th August, 1914, Britain declared war on Germany. Unbelievably, despite of the outbreak of war, both football associations, the SFA and the FA, sanctioned the replay – of a friendly!

One hundred years later, as we commemorate the bravery of all that fought – and died – in the trenches, questions remain: Why did this match go ahead at all? What was its significance? Why was it so ‘contentious’? Nevertheless, on 1st September, 1914, four weeks after the outbreak of World War 1, Celtic played and won the replay by 2 goals to 1 despite playing the whole of the second half with only 10 men; Peter Johnstone sitting out the second half due to a foot injury.

However, Celtic’s first European Cup – a silver trophy in the shape of a lighthouse – was never presented and was, most likely, melted down to assist with the German war effort.

On the 23rd April, 1988 – 74 years later – in a jam-packed Celtic Park, the Centenary title was secured with many supporters sitting on the trackside! Celtic took to the field to a glorious rendition of ‘Happy Birthday Dear Celtic’ before clinching their title by defeating Dundee 3-0 with goals from Chris Morris and a brace from Andy Walker. Attending Celtic Park on that day was an official delegation from Hungarian Club, Ferencvaros, which was headed by the club’s Chairman, Zoltan Magyar.

Formed in 1899 and named after Budapest’s ninth district, Ferencvaros was in attendance in Paradise to make an important, if somewhat belated, presentation to Celtic, The Ferencvaros Vase; a beautiful white and gold trophy decorated with painted butterflies and floral patterns which remains on display at Celtic Park to this day as a testament to Celtic’s early European success; a success that will always be witness to the vision of manager, Willie Maley, and the ability of players such as captain, ‘Sunny’ Jim Young, Patsy Gallacher, Jimmy ‘Napoleon’ McMenemy, Charlie Shaw and Peter Johnstone.

The war that, in 1914, many had predicted ‘would be over by Christmas’ raged on. Peter wanted to ‘do his bit’. He was a single-minded individual who, at times, Maley regarded as a loose cannon. The two men often argued. Many players who passed through the front doors of Celtic Park were afraid of Maley; an imposing figure who, like Jock Stein many years later, could bully and intimidate weaker men. However, ‘Big Peter’, as Maley called him, was not one of them. Peter’s ability on the park kept him in the team but he was not afraid of the manager; he would fight his corner, speak his mind; in fact, his bravery was the quality that had convinced Maley that he had found the ideal replacement for Willie Loney in the first place. But it was the same quality that would result in his untimely death at the age of just 29.

There was no conscription at the beginning of the war and the army relied on the tens of thousands of brave volunteers, many of whom never returned. In 1914, while top of the old First Division, 16 players from Heart of Midlothian FC – who had defeated Celtic in the opening day of the 1914-1915 season – joined up with the 16th Royal Scots known as ‘McCrae’s Men’; a battalion formed by Sir George McCrae, a former MP for East Edinburgh, who had launched a campaign to recruit 1000 men in the space of a week. Seven of those Hearts players paid the ultimate price: John Allan, James Boyd, Duncan Currie, Ernest Ellis, Tom Gracie, James Speedie and Harry Wattie. Players from Raith Rovers, Falkirk, Dunfermline and Hibernian also joined the battalion, never to return.

In November, 2004, in the town of Contalmaison in northern France, the McCrae’s Battalion Great War Memorial was unveiled. It is known as the Contalmaison Cairn, and it has become a place of pilgrimage for many football fans from the east of the country. They were regarded as heroes, as were players from football clubs in the west, north and south of Scotland; and we, as Celtic supporters, would never be so disingenuous as not to recognise all of them.

In newspapers, however, football was regarded as a sport for ‘war dodgers’. Peter, who had a newsagents business in Glasgow, would have been acutely aware of these accusations in the press.

Then, in March 1916, due to the shortages of men, the government passed the Military Services Act and conscription became a reality for all single men between the ages of 18 and 41. A second Act in May that year extended conscription to married men, the only exceptions being clergymen, teachers, the infirm and men in ‘listed occupations’: utility workers, scientists, rail workers, farmers, dock workers, merchant seamen and miners.

Peter Johnstone was a miner and, therefore, exempt. However, he was determined to volunteer for active service and no effort from Maley could dissuade him. He left Celtic on the 11th March, 1916, and, on 25th May, 1916, Peter joined the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. He played his last match for Celtic in a 3-2 Glasgow Cup final victory against Clyde at Celtic Park on 7th October, 1916, while he was home on leave. But Peter’s frustrations continued: his reputation had gone before him and he remained anchored on home soil to play for the regimental football team, a situation that was not to his liking. Determined; Peter made up his mind and he requested a transfer in order to ‘see some action’.

Peter joined the 6th Battalion of the Seaforth Highlanders and, under the command of Field Marshall Allenby, took part in the Battle of Arras, France, which began on 9th April, 1917. Allied troops from Britain, Canada, Newfoundland, Australia and New Zealand attacked German troops near the French city of Arras on the Western Front; a British offensive planned in collaboration with the French High Command. The aim was to bring about an end to the war in 48 hours.

The Royal Flying Corps had entered the battle with inferior aircraft to the Luftstreitkrafte. Dominance over the Arras airspace was essential and the mission became increasingly dangerous with the arrival of the Red Baron, Manfred Von Richthofen and his ‘Flying Circus’ or ‘Jastas’. In the air, numbers of casualties increased among Allied pilots in what came to be known as ‘Bloody April’. It was said that, in 1917, the average flight life of a Royal Flying Corps was 18 hours.

Peter and his comrades on the ground made territorial gains but little to alter the strategic situation at the Western Front. Some historians believe that the result of the battle was indecisive although it was tactically regarded as a victory due to the capture of Vimy Ridge, an area of high ground previously held by the Germans. But the advance came at a devastating cost: from the 9th April to the 16th May, 1917, the Allies suffered 158, 660 casualties who were either killed, wounded or ‘missing presumed dead’. Among them was Private Peter Johnstone, service number: 285250, who died sometime between the 12th and 16th, May, 1917.

Soon, rumours of Peter’s death filtered across the Channel and reached Glasgow. The terrible news was confirmed on 6th June. There was not a family in the country that had not already been touched by death in the three years of the war, yet the news of Peter’s passing sent shockwaves across the country. It was incomprehensible that a Celtic player, a celebrity, had been killed.

Manager, Willy Maley – shaken and visibly upset – entered a state of melancholy. He questioned himself: was it his temperament, their disputes, or a clash of personalities that had been the catalyst for Big Peter’s determination to go to war? He went to see Isa Johnstone, Peter’s widow. He assured her that the club would take care of the arrangements and helped her with her application for a war pension. Celtic football club had lost one of their own.

Perhaps surprisingly, at Celtic Park, little has ever been done to commemorate the death of Big Peter, a war hero, and arguably, the most prominent of Celts to fall in the bloodiest of all wars. His body was never found and is commemorated only by a dedication inscribed at the Arras Memorial in the Faubourg d’Amiens Cemetery, Boulevard du General de Gaulle, Arras, France, along with 2647 identified casualties; 10 remain unidentified.

This year, 2014, marks the centenary of the outbreak of World War 1 in which 16 million brave men were killed. We will remember them. The Celtic family will remember Peter Johnstone; he was one of them. He was also a son, husband, father, miner and true Celt.

Rest in peace, Peter.

Peter Johnstone: A hero of the green fields

Source: http://www.celticfc.net/news/5896

By: Joe Sullivan on 16 May, 2014 14:30

IT was 97 years ago today, on May 16, 1917 that Celtic player, Peter Johnstone was reported missing, presumed dead on the mud-sodden former green fields of France.

It was a few months earlier on October 7, 1916 that Peter Johnstone won his last medal as a Celt in his last game for the club, the last of 13 medals in eight years as a first-team player and, like his first, it was a Glasgow Cup win

However, following this last game, a 3-2 win over Clyde, he didn’t join another club, he didn’t retire from the game – after picking up his medal, the 28-year-old simply re-joined his company in the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders as Private 285250 and never returned to the Hoops.

The First World War had claimed another victim. It was a conflict which affected individuals, families, communities and organisations in every country caught up in the war, and Celtic Football Club was no different.

As the world was plunged into war in 1914, all aspects of life changed and as millions headed off to the Front, the Great War was to have its effect on Celtic and a number of its players.

As the war progressed the implications for the game were significant. Player salaries were reduced, employment in munitions factories on Saturdays resulted in a sharp fall in attendance, both by spectators and players and the pressure to complete the fixture card was significant.

Indeed, Celtic was forced to play two matches, against Raith Rovers and Motherwell, on the same day in 1916 in order to comply – ironically, those two games in the one day were the only games missed by Johnstone that entire 1915/16 season.

Football grounds were viewed as an ideal venue for recruitment drives and during one such event Celtic manager Willie Maley endorsed a mock trench warfare at Celtic Park designed to lure players and spectators alike to the Front.

Such drives had their successes and the supporters and officials of Hearts and Queen’s Park watched as their first-team players enlisted almost en bloc. Whilst there wasn’t a mass exodus from Celtic, a number of players did enlist and sadly, some failed to return.

Willie Angus, John McLaughlin, Archie McMillan, Leigh Roose, Donnie McLeod, Robert Craig and Peter Johnstone all played on the field of Celtic Park and fought in the Great War and for their lives in the fields of France and Belguim.

Centre-half and utility man, Peter Johnstone, was the best known Celt to have fallen in the Great War.

He signed for on January 9, 1908 made his debut in April the following year, the first appearance of 233 for the club. During this period Johnstone scored 19 goals.

Johnstone, a miner signed from Glencraig Celtic after spells with Buckhaven and then Kelty Rangers, was an idol of the Celtic faithful and was a deserved recipient of such accolade when he lifted his first Scottish Cup medal after the final with Clyde in 1912.

In the same year he added another gong to his collection when Celtic met and beat Clyde in the Charity Cup final in an amazing tie that Celtic won by seven corners to nil.

However, his first ever medal for Celtic was in the Glasgow Cup final of October 9, 1909 when a 55,000 crowd at Hampden saw Jimmy Quinn score the only goal of the game against Rangers.

In all, his medal haul was four championships, two Scottish Cups, three Glasgow Cups and four Charity Cups.

It’s no wonder that Peter Johnstone, who was born on July 6, 1888, a momentous year in the history of the club, was known as a utility player.

He arrived as a forward and ended up playing at centre-half among other positions and he even played in goal!

On May 29, 1911, the Bhoys played a game in Budapest on a continental tour, and despite selecting forward Peter Johnstone in goals, they took the spoils in a 2-0 win thanks to a double from Willie Nichol.

The following day, local paper, ‘Sport Futar’, described Celtic’s victory as the ‘best display ever seen in Buda-Pesth’. Willie Maley’s men also drew 1-1 with Ferencvaros on the trip with Andy McAtee on target.

Johnstone was also part of the infamous side who contested for the ‘missing’ Ferencvaros Cup in Budapest against Burnley in 1914.

The game ended in a draw and it was reluctantly agreed that a return would be played in Burnley. Celtic won and the trophy never materialised but compensation was afforded to Johnstone and his team mates when they secured the Double in 1914.

Johnstone was eager to transfer from the field of play to the field of War, and was recruited to firstly the 14th Battalion of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders in 1916 and latterly the 6th Battalion of the Seaforth Highlanders.

He initiated this move in order to secure quicker passage to the Front. Whilst eager to do his bit, Johnstone was also always willing to assist the Celts and during his army training he travelled overnight from England to help his team-mates oust Rangers from the Glasgow Cup on September 23, 1916 – he scored in the 3-0 win watched by 60,000 at Celtic Park and his next game, the final against Clyde., proved to be his last

To the absolute shock of the Celtic faithful Johnstone lost his life at some point between the 12th and 16th of May during the Battle of Arras in 1917. A Celtic Legend, Johnstone’s death was a huge loss to Celtic Football Club.

A dedication to his memory is inscribed on Bay 8 of the Arras Memorial in the Fauborg d’Amiens Cemetery.

Moves are now well underway in his home Kingdom of Fife by the Peter Johnstone Memorial Committee backed by the Ballingry Celtic Supporters’ Club to have a memorial garden in honour of the former Celt.

Celtic’s Peter Johnstone died in battle 100 years ago this week

http://www.celticfc.net/news/12617

By: Joe Sullivan on 16 May, 2017 08:44

IT was on October 7, 1916 that Peter Johnstone won his last medal as a Celt in his last game for the club, the last of 13 medals in eight years as a first-team player and, like his first, it was a Glasgow Cup win

However, following this last game, a 3-2 win over Clyde, he didn’t join another club, he didn’t retire from the game – after picking up his medal, the 28-year-old simply re-joined his company in the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders as Private 285250 and never returned to the Hoops.

The First World War had claimed another victim. It was a conflict which affected individuals, families, communities and organisations in every country caught up in the war, and Celtic Football Club was no different.

As the world was plunged into war in 1914, all aspects of life changed and as millions headed off to the Front, the Great War was to have its effect on Celtic and a number of its players.

As the war progressed the implications for the game were significant. Player salaries were reduced, employment in munitions factories on Saturdays resulted in a sharp fall in attendance, both by spectators and players and the pressure to complete the fixture card was significant.

Indeed, Celtic were forced to play two matches, against Raith Rovers and Motherwell, on the same day in 1916 in order to comply – ironically, those two games in the one day were the only games missed by Johnstone that entire 1915/16 season.

Football grounds were viewed as an ideal venue for recruitment drives and during one such event Celtic manager Willie Maley endorsed a mock trench warfare at Celtic Park designed to lure players and spectators alike to the Front.

Such drives had their successes and the supporters and officials of Hearts and Queen’s Park watched as their first-team players enlisted almost en bloc. Whilst there wasn’t a mass exodus from Celtic, a number of players did enlist and sadly, some failed to return.

Willie Angus, John McLaughlin, Archie McMillan, Leigh Roose, Donnie McLeod, Robert Craig and Peter Johnstone all played on the field of Celtic Park and fought in the Great War and for their lives in the fields of France and Belguim.

Centre-half and utility man, Peter Johnstone, was probably the best known Celt to have fallen in the Great War.

He signed for on January 9, 1908 made his debut in April the following year, the first appearance of 233 for the club. During this period Johnstone scored 19 goals.

Johnstone, a miner signed from Glencraig Celtic after spells with Buckhaven and then Kelty Rangers, was an idol of the Celtic faithful and was a deserved recipient of such accolade when he lifted his first Scottish Cup medal after the final with Clyde in 1912.

In the same year he added another gong to his collection when Celtic met and beat Clyde in the Charity Cup final in an amazing tie that Celtic won by seven corners to nil.

However, his first ever medal for Celtic was in the Glasgow Cup final of October 9, 1909 when a 55,000 crowd at Hampden saw Jimmy Quinn score the only goal of the game against Rangers.

In all, his medal haul was four championships, two Scottish Cups, three Glasgow Cups and four Charity Cups.

Johnstone was also part of the infamous side who contested for the ‘missing’ Ferencvaros Cup in Budapest against Burnley in 1914.

The game ended in a draw and it was reluctantly agreed that a return would be played in Burnley. Celtic won and the trophy never materialised but compensation was afforded to Johnstone and his team mates when they secured the double in 1914.

Johnstone was eager to transfer from the field of play to the field of War, and was recruited to firstly the 14th Battalion of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders in 1916 and latterly the 6th Battalion of the Seaforth Highlanders.

He initiated this move in order to secure quicker passage to the Front. Whilst eager to do his bit, Johnstone was also always willing to assist the Celts and during his army training he travelled overnight from England to help his team-mates oust Rangers from the Glasgow Cup on September 23, 1916 – he scored in the 3-0 win watched by 60,000 at Celtic Park and his next game, the final against Clyde., proved to be his last

To the absolute shock of the Celtic faithful Johnstone lost his life at some point between the 12th and 16th of May during the Battle of in 1917. A Celtic legend, Johnstone’s death was a huge loss to Celtic Football Club. A dedication to his memory is inscribed on Bay 8 of the Arras Memorial in the Fauborg d’Amiens Cemetery.

![[Untitled] [Untitled]](https://wikifoundryimages.s3.amazonaws.com/c532bfe718eb601b0c868fdcd64d9323)