| Celtic’s Foundation | About Celtic | Celtic Committee |

In the Beginning

| “[A football club will be formed] for the maintenance of the dinner tables of our needy children.” After the famous meeting in the hall of St Mary’s, Calton, in November 1887 |

(below courtesy of www.walfrid-og.net)

Born Andrew Kerins, in 1840, in Ballymote, Sligo, in the West of Ireland, Brother Walfrid would experience, at the closest of proximities, the full horrors of the Great Famine in Ireland, before ‘escaping’ his rural life to join the Marist Order, where he became a schoolteacher.

Sligo was fated to endure the worst of the Famine, though it is not known how the Kerins family fared during the turmoil. However, being that the Kerins family was of farming stock, it is safe to assume that they would not be left untouched by tragedy.

A consequence of the Great Famine, Ireland’s rural population fled the countryside to the towns and cities where, in Ireland, the disaster was no less biblical in its proportions. The result was an exodus of Irish folk to mainland Britain (and some also to The New World), and specifically the cities of the Industrial Revolution – notably, Glasgow, Liverpool, Manchester, London, Edinburgh and Dundee.

Awaiting them was work, albeit poorly paid, menial and unskilled, and, of course, slum living conditions, disease and terrible, unimaginable deprivation.

Sadly, the establishment, the ruling classes, the Government and the Protestant Churches of Scotland and England did more than their fair share to alienate the Irish immigrants, who were seen to be and treated as though they were less than human. Glasgow was no exception to the British rule, as the Irish and Brother Walfrid would discover.

Brother Walfrid had taken his religious name, as was the practice of the Marist Order, to signify the cutting of all ties with ‘life in the world’, but he would remain a man that was haunted by that which he had witnessed in Ireland. It was a horrific reality that would not be exorcised amongst the grotesque slums of Glasgow’s East End, where Brother Walfrid arrived in the early 1870s.

The squalor, deprivation, poverty, decay, disease and human suffering of the ‘Empire’s Second City’ – the most densely populated city in Europe, at that time – can scarcely be imagined by us today. The bold attempts by modern day film- makers to depict the full extent of the horror of the impoverished population of industrialised, Victorian Britain are woefully inadequate; as are the televised works of Dickens, where the children are rosy-cheeked and cherub-like and not, as they should be in the interests of historical accuracy, scarred by disease, waif-like, filthy dirty, dressed in rags and clinging barely to life.

However, the statistics are graphic enough. Of the 11,675 registered deaths (and that is registered – there would be many more) in Glasgow in 1888, 4,750 were children under five years of age. It was a nightmare best not revisited, or even contemplated, though there are, sadly and shamefully, modern equivalents yet remaining on this Earth.

This, then, was the gruesome world that Brother Walfrid devoted his life in Glasgow to combating.

Brother Walfrid worked like a man possessed, with zeal and enthusiasm, compassion and care, kindness and courage, dedication and energetic vigour in this wretched environment of despair and pain. As a teacher at St Mary’s and then as headmaster at Sacred Heart School in Bridgeton, Brother Walfrid witnessed at first hand the full extent of the plight of the poor, the needy, the starving and the suffering.

The children of this misery were, however, his prime concern. Aside from educating the children of the slums, Brother Walfrid also sought to feed and clothe them. To do so, he was instrumental in establishing, in 1884, the ‘Penny Dinners’ for his poverty-stricken pupils and the children of his parish.

In order to achieve this aim, Brother Walfrid had enlisted the aid of the St Vincent de Paul Society, itself introduced into the Archdiocese of Glasgow in 1848.

Thereby, Brother Walfrid attempted to ensure that his children received a warm and nourishing meal each day for their penny. In Walfrid’s very own words:

| ‘Should parents prefer, they could send the bread and the children could get a large bowl of broth or soup for a halfpenny, and those who were not able to pay got a substantial meal free. This has been a very great blessing for the poor children.’ |

However, two separate events dictated to the devout and compassionate Walfrid that his efforts, and those of his Marist colleague, assistant and headmaster of St Mary’s, Brother Dorotheus, were wholly insufficient.

Firstly, the activities of the Presbyterians were a great concern, given that the Protestant Church was also active in feeding and attending to the poor of the East End, while simultaneously trying to ‘snare away’ Brother Walfrid’s flock. Brother Walfrid enjoyed a close and warm relationship with his Protestant cousins, but he was also fearful of tactics that he’d witnessed in his homeland, Ireland, of turning the poor against the Catholic Church.

Secondly, poverty was worsening – dramatically and horrifically so. Brother Walfrid needed to do more and find a focus for the community to stand together behind.

Arguably, there were four main ingredients that had to be introduced into the embryonic idea of Celtic:

– charity (to feed and clothe the East End’s poverty- stricken),

– religion (to assist the Catholic Church in fighting off the advances of Protestantism recruitment, when people were at their most vulnerable and therefore most amenable to targeting for recruitment by missionaries, and also of course to cement the relationship of trust, compassion and caring between the Catholic Church and its flock),

– culture (to provide a much needed focus, identity and symbol for the Irish Catholic population of Glasgow)

– and, of course, politics.

The charitable aspirations and intentions of Brother Walfrid and Brother Dorotheus are well established. Others would become involved with this philanthropy.

Undoubtedly, Walfrid was also aware of the ever-increasing influence of the Protestant Church in Glasgow’s East End and of the dangers that entailed, as far as he and the Archdiocese of Glasgow were concerned. He would also have been alarmed at the extremes of anti-Catholic prejudice within the endemic Scottish community and also within the Protestant Church – ironic, given its simultaneous benevolence towards the Irish Catholics of the East End – and also the gradual rise of Orange-ism in Glasgow.

However, it is less well recorded that some of the ‘official’ Presbyterian anti-Catholic doctrine was, in effect, a defence mechanism to deflect attention from the schisms within Presbyterianism itself, at that time. Anti-Catholicism was all that united a divided Protestantism. Brother Walfrid said: ”Twas the most dangersome time for the young fellos, jest afther they had left school, an’ begun t’ mix up wid Protestand boys in the places where they wor workin’.’

Culturally, Brother Walfrid would also have seen the need to provide his Irish Catholic flock with a focus, an identity and a symbol, away from the Church. This symbolism of pride and achievement and Irish-ness already had a template – it was called Edinburgh Hibernian.

Founded in 1875 by Canon Edward Hannan, Edinburgh Hibernian had become, not only a successful football club in its own right, but also a symbol for the Irish throughout Scotland. Hibernian was, however, run exclusively for the Catholic Irish and was greatly influenced by the temperance movement of the age – the demon drink being seen by many as the cause of so many evils in society.

Brother Walfrid would learn much from Edinburgh Hibernian and would also, in time, be both inspired by Hibernian and disregarding of its template for his own vision.

Politics

The political opinions of Brother Walfrid will forever remain a secret. What cannot be denied, however, are the politics of those that surrounded the Marist priest. Ireland and Britain were hotbeds of political ideologies in the 19th Century, and these ideologies would impact on the embryonic concept of a Celtic Football Club. Indeed, had they not done so, our Club may not have survived, falling by the wayside like so many others, and our Club may not have been born with the genetics for equality, liberty, fraternity, integration and non-sectarianism at is very core.

Walfrid surrounded himself with men who were the driving forces behind many of these political ideologies – men such as John Glass, Pat Welsh, Dr. John Conway, James Quillan, William McKillop, John O’Hara, Thomas Flood, J.M. Nellis, Joseph Shaughnessy and Hugh and Arthur Murphy. Brother Walfrid would also have connections with John Ferguson and Michael Davitt. It must be assumed that he did so by choice. It was a wise choice, indeed.

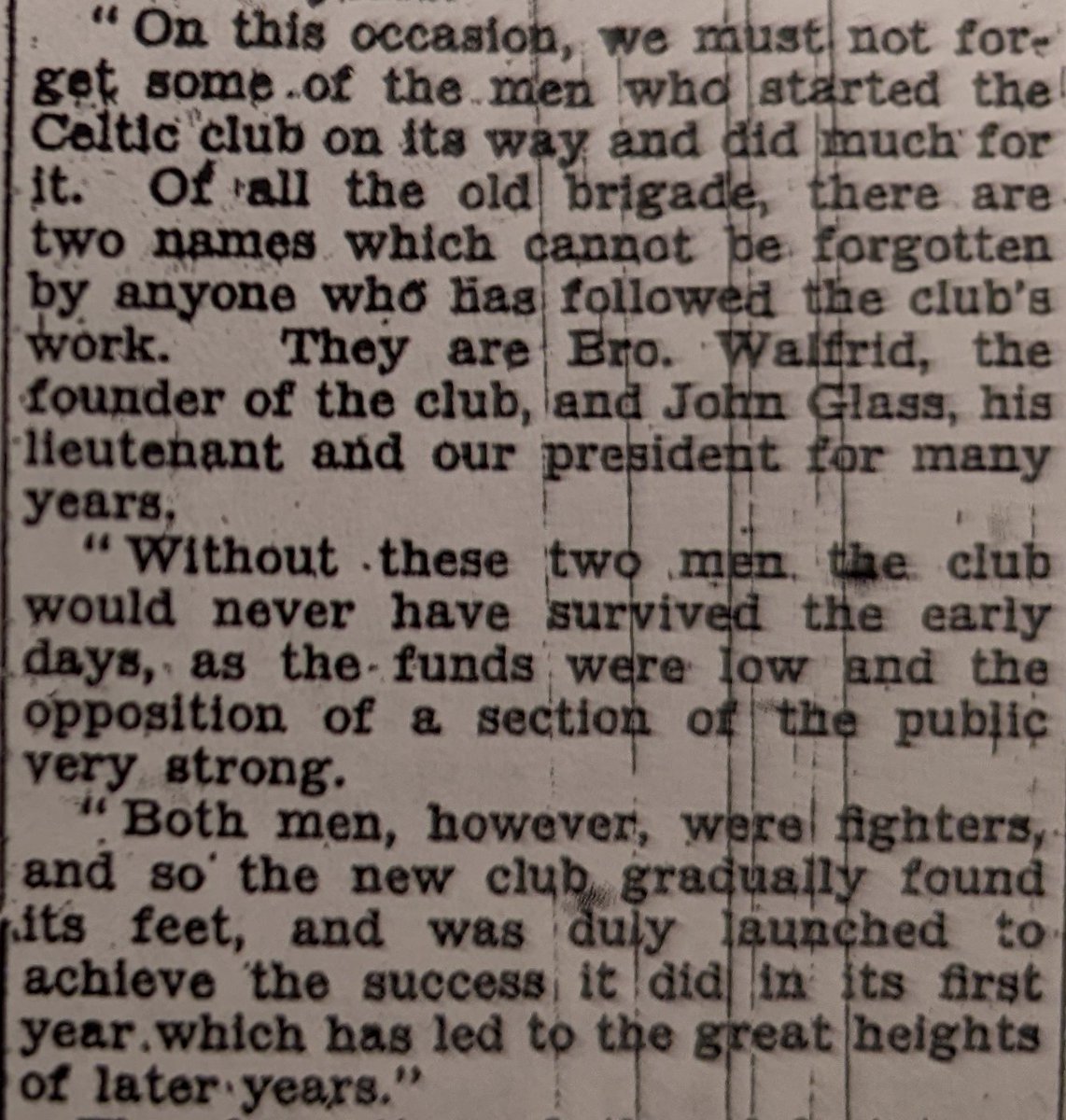

Brother Walfrid had, through his charitable, teaching and ecumenical activities, collated a considerable database of contacts, colleagues, friends and acquaintances, many of whom would be of sterling use in the founding of Celtic; each would bring his own unique attributes to the table of creation. Indeed, Brother Walfrid was later described by Tom Maley, former Celtic player, Celtic committee man and brother of then Celtic manager, Willie Maley, as: ‘A wonderful, organising power… of lovable nature’ and a man who ‘only had to knock, and it was opened.’ Admirable qualities, and they would be very useful in the art of persuasion, when it was necessary.

Of course, the fact that Brother Walfrid was both respected and revered throughout Glasgow, for his charitable works and devotion to the poor, would also be an undeniable attraction for assistance. Each of the men that Brother Walfrid associated with in the formation of the fledgling Celtic concept were philanthropists, successful men in their own fields of expertise and, crucially, they were politically active to varying degrees.

Political astuteness would be fundamental for the choices that lay ahead. Had they not chosen the path that they did, the longevity and success of Celtic would have been compromised from the beginning.

Patrick Welsh, for instance, had been, in Ireland, a Fenian activist. For weeks in 1867, Welsh had been on the run from the British authorities, but was apprehended by a 37- year old British soldier – Sergeant Thomas Maley of the Royal North British Fusiliers – at Dublin quay, as Welsh was attempting to flee his country of birth for the prospect of a new and peaceful life in Scotland. Fortunately for Welsh, whose fate might have been imprisonment or the gallows, Sergeant Maley was an Irish Catholic who had wrestled with his conscience while serving Queen Victoria in Ireland. Also fortunately for Pat Welsh, there were no other witnesses to his capture.

Sergeant Maley, whose third son, Willie, would be born the next year, demanded that Welsh would not break their own peace treaty and Maley allowed the eternally grateful Pat Welsh to escape to Scotland. Pat Welsh would become a master tailor with premises on fashionable Buchanan Street, Glasgow, where he would prosper both as a businessman and as a family man. He kept his word to Sergeant Maley and, in the years to come, recognising that Maley could have faced court-martial for his act, Pat Welsh remained firm friends with Thomas Maley when the soldier retired from the British Army and moved to Cathcart village, near Glasgow, with his Scottish wife and their four sons, Charles, Tom, Willie and Alec.

This was, also, a twist of fate that would hugely benefit Celtic. Sergeant Maley’s second son, Tom, would play for Celtic and would also become a Celtic committee man. Willie would do likewise, though Willie is also known as ‘Mr Celtic’ for what he achieved for the Club over a fifty-year period. And all because of a selfless act of humanitarianism!

The name of John Glass repeats itself throughout research into the creation of Celtic. Undoubtedly, Brother Walfrid was the architect, the instigator, the motivator and the conduit to all the facets that would come together. John Glass, however, was the master builder and the catalyst for it all to happen.

His importance should be recognised. John Glass was a joiner, a man with many contacts in the building trade and a son of Donegal. He was also, we are told, a man that could ‘charm the birds down from the trees’ such was his charisma. This charm and persuasiveness would be a highly useful tool in Celtic’s formation, as Glass is widely acknowledged to be the man who persuaded a number of famous football players of the time to join the fledgling Club. A humanitarian and a meticulous organiser, Glass was also a leader of men, and specifically a dignified and highly respected leader of the Irish Catholic community. John Glass was THE politician sitting at the round table deliberating the creation of Celtic. Glass was later described by Willie Maley as the man ‘to whom the Club owes its existence.’

Ferguson and Glass organised several political rallies at which Michael Davitt addressed the Highland crofters. The question must therefore be asked: did the name ‘Celtic’ originate from this popular political influence of the day, and did Brother Walfrid and John Glass see in this name a method to celebrate Irish-ness, symbolise Irish-ness, yet simultaneously join hands with Scottish Celts? After all, historically speaking, the peoples of Ireland and Scotland were one and the same – Celts!

The Irish and the Scots working classes had two things in common: the mutual fight for survival and a love of football. Brother Walfrid had, for some time, been aware of the profound popularity of the sport of football. Indeed, he had himself organised many games to provide funds for the ‘Penny Dinners’, and with considerable success too.

Edinburgh Hibernian was the team that his Irish Catholic flock was more than happy to pay to see, and Brother Walfrid recognised both this and the fact that Edinburgh Hibernian had become a symbol of Irish-ness, culture, religion and success in Scotland. It was a potent and powerful mix that Brother Walfrid would soon learn could be harnessed for a multitude of community benefits.

On February 12th 1887, Edinburgh Hibernian won the Scottish Cup, the country’s premier and most coveted trophy, by defeating Dumbarton 2:1 at Hampden Park, Glasgow. The triumph was celebrated joyously by Irishmen throughout Scotland and, indeed, the scenes of jubilation in Glasgow were a match for those in Leith, Edinburgh.

This, then, was the power of football and also the symbolism of success for the Irish community. Edinburgh Hibernian were feted as the victors by Glasgow’s Irish and the triumphant team was taken to St Mary’s Hall in the Calton district of Glasgow to receive the spoils of jubilant victory. Amongst the rapturous throng were Brother Walfrid and John Glass. Dr John Conway led the speeches in praise of Edinburgh Hibernian, the gathering sang ‘God Save Ireland’ and John McFadden, the Hibernian’s secretary, was so moved by the warmth of the reception and the fervour of the hospitality that he, perhaps jokingly, suggested that his hosts should ‘go and do likewise’!

Brother Walfrid accepted the gauntlet of the challenge. After all, if Edinburgh could produce a successful Irish football team then surely Glasgow could do likewise, given the far greater Irish population in Glasgow.

As an indication of the margins between longevity of life for a fledgling football club and inauspicious demise in a pauper’s grave, one needs only look at the names of the clubs that registered with the Scottish Football Association on August 21st 1888: Celtic Football and Athletic Club, Champfleurie and Adventurers of Edinburgh, Leith Harp, Balaclava Rangers from Oban, Temperance Athletic of Glasgow, Whifflet Shamrock and Britannia of Auchinleck. Brother Walfrid and his associates would come to ponder the mechanics required for a successful launch and, of course, a sustainable flight.

The objectives were, however, clear enough: the funding of charities in Glasgow’s East End, notably Brother Walfrid’s ‘Penny Dinners’; a focus, an identity, a symbolism for the Irish Catholic population where a successful football club could and would sustain the morale of an otherwise frequently demoralised people; a route to health and fitness for the young men of the area and a method to keep them distracted from alcohol; a way to combat, through self-finance, the influence of the Presbyterians in the East End and, perhaps most importantly of all, a symbol of hope when around them there was so much despair. But, how?

The Club is formed

On the afternoon of Sunday November 6th, 1887, a meeting to constitute the formation of the Celtic Football and Athletic Club was called to order by John Glass. Through arduous discussions and, at times, heated debates, the pivotal and crucial decisions had been made that would cement the structure of Celtic. The choices were wise, indeed. Initially, the local parishes of St. Mary’s, St Andrew’s and St Alphonsus’ had been involved, but the ‘mother parish’ of St Mary’s had been the driving force and, consequently, some disgruntled individuals departed the scene, no doubt disillusioned by the abandonment of the principles of the template for such a venture, Edinburgh Hibernian.

Edinburgh Hibernian was an organisation with the temperance movement at its core. Celtic was not to be that. Brother Walfrid, John Glass, Pat Welsh et al would realise the fundamental importance of Celtic being managed with business acumen and financial expertise in order to survive and sustain itself during what could be a troubled birth, a precarious childhood and even a fraught adolescence.

Only adulthood – a long way off – would provide a modicum of comfort. So, why exclude the monies of the License Trade when that money could be used for the benefit of the Club? And, with such a partnership (albeit with the demon drink), immediate funds and employment (although, in some cases in name only) could be found to attract football players to Celtic – all amateurs, of course, though their expenses would not fool even the most average of accountants!

Edinburgh Hibernian also operated a Catholic only employment policy. This exclusivity would be disregarded by the founding fathers of Celtic – a bold and courageous move, given the prejudices of the era, and one that would be embraced for ever more by Celtic.

Willie Maley, Celtic’s manager for over forty years, summarised this fundamental of a non-sectarian Celtic when he later said: ‘It is not his creed nor his nationality which counts -it’s the man himself.’

Indeed, Maley would openly boast of the Protestants, Hindus, Jews and Muslims that had been – and were – in the employ of Celtic, though in reality the Club was, at its roots, Catholic and Irish, proudly and justifiably so. This non-sectarian fundamentalism had the fingerprints of John Glass’ politics all over it and, in fact, was the principle that set Celtic apart, from the outset. When one considers the undeniable temptation to be exclusivist in the face of such provocation – prejudice and bigotry were the norm – it was a brave, indeed socialist and humanitarian, move and one that paved the way for the likes of John Thomson, Jock Stein, Danny McGrain, Kenny Dalglish and, yes, Henrik Larsson, not to mention the non-Catholic Tims that would be attracted to the Celtic Cause.

Of course, there were voices of dissent and attempts were made to rewrite Celtic’s constitution so that ‘only the right sort’ could be employed by and play for Celtic. Such malcontents were especially evident when, in 1897, Celtic became ‘Celtic Football and Athletic Company Limited’. One such breakaway formed the short-lived Glasgow Hibernian. The dissenters lost, however, and Celtic is culturally wealthier as a result.

The options for the christening ceremony for Celtic were considerable and numerous, but somewhere along the line, Brother Walfrid, perhaps inspired by Glass, insisted that the name should be Celtic.

But, Seltic or Keltic?

Most scholars believe that Brother Walfrid preferred the Keltic pronunciation, but the ‘soft C’ was adopted. Whatever the minutiae, the choice of name was inspired and one ponders whether the impact of our Club would have been quite the same had ‘she’ been christened Erin, Hibernian, Shamrock or Emerald? After all, Celtic, as a name, symbolised precisely what the Club was all about in the first place. As with the people ‘she’ represented and for whom ‘she’ would compete and triumph and for whom ‘she’ would become an irresistible attraction (to both Catholic and, in time, also Protestant and other faiths), Celtic, the name, symbolised a club that had been born in Scotland of Irish parents, had been lovingly raised by an Irish Catholic family, had been tutored and schooled in Scotland amongst Irish and Scots, of whatever denomination, and had been graduated by an, ultimately, global university.[Link: Celtic the Name, Celtic the Pronunciation]

Would it have worked so beautifully otherwise?

Certainly, Celtic immediately caught the mood – Archbishop Eyre of the Glasgow Archdiocese was top of the subscription list of the new Club – and, in January 1888 the following statement was released:

| CELTIC FOOTBALL AND ATHLETIC CLUB Celtic Park, Parkhead (Corner of Dalmarnock and Janefield Streets) Patrons His Grace the Archbishop of Glasgow and the Clergy of St Mary’s, Sacred Heart and St Michael’s Missions, and the principal Catholic laymen of the East End.

The above Club was formed in November 1887, by a number of Catholics of the East End of the City. The main object is to supply the East End conferences of the St Vincent de Paul Society with funds for the maintenance of the ‘Dinner Tables’ of our needy children in the Missions of St Mary’s, Sacred Heart and St Michael’s. Many cases of sheer poverty are left unaided through lack of means. It is therefore with this principal object that we have set afloat the ‘Celtic’ and we invite you as one of our ever-ready friends to assist in putting our new Park in proper working order for the coming football season. We have already several of the leading Catholic football players of the West of Scotland on our membership list. They have most thoughtfully offered to assist in the good work. We are fully aware that the ‘elite’ of football players belong to this City and suburbs, and we know that from there we can select a team which will be able to do credit to the Catholics of the West of Scotland as the Hibernians have been doing in the East. Again there is also the desire to have a large recreation ground where our Catholic young men will be able to enjoy the various sports which will build them up physically, and we feel sure we will have many supporters with us in this laudable object.’ |

There were two problems of immediacy. Firstly, Celtic had to find a home and, secondly, Celtic needed to find players.

Within a week of being constituted, Celtic had leased an area of ground off the Gallowgate in Parkhead, bounded on the west side by Janefield Street and on the east by Dalmarnock Street (now Springfield Road). Within six months, a voluntary workforce had built a ground that emulated the highest standards of the time.

There was a level, grassy playing field measuring 110 yards long and 66 yards wide, a basic earthen terracing around three sides of the stadium and an open-air stand (capable of accommodating 1,000 spectators) that contained a pavilion, a referee’s room, an office, dressing rooms and washing and toilet facilities.

It should be recorded at this point that the ‘old’ Celtic Park is NOT the location of the current Celtic Park. In 1891, Celtic experienced trouble, yet again, with their greedy landlord (how ironic, given the nature of the land disputes in Ireland) when he, rather optimistically, increased the rent from £50 per annum to £450. Celtic’s committee men were far too shrewd and fleet of foot, business wise, to tolerate such opportunism and, consequently, Celtic chose to relocate.

We moved across the Janefield Street Cemetery to ‘Paradise’, our current home and, once again utilising a volunteer workforce, built a second Celtic Park in time for the start of the 1892-93 season.

Links

Articles

Articles

This is the text of the fundraising circular sent round the parishes in January 1888, very likely to have been written by Brother Walfrid himself, which states clearly the objective of the club at our foundation.