| Lisbon Lions | The Match | Pictures | 1966–1967 |

A Victory for Football – When the Lions Devoured Catenaccio

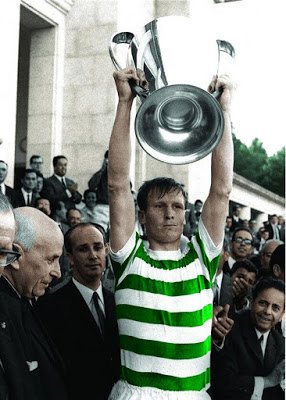

THE image of a sweat-soaked, sun bathed Billy McNeil hoisting aloft the European Cup has become a treasured icon to Celtic supporters. It symbolises the club’s greatest ever achievement and provides a constant reminder and inspiration to younger generations of just how high this great club can reach.

The rightful reverence given to that famous night in Lisbon’s Estadio Nacional is primarily in acknowledgment to the fact that a home grown team from the west of Scotland should achieve the seemingly impossible by lifting European football’s greatest prize.That feat alone is of course worthy of celebration but in truth it is just part of what makes the story of Jock Stein and the Lisbon Lions so special.

You see what the Bhoys achieved on May 25th 1967 is something which was a cause for celebration far beyond Scotland, Ireland and those other traditional Celtic strongholds across the globe. The reason for that is simple. Celtic’s victory was a victory for football. It was a victory for the so-called small people.

The dreamers.

To fully comprehend the magnitude of this feat you have to understand exactly what Celtic had to overcome in the heat of the Portugese capital. Helenio Herrera’s Inter Milan v Celtic should have been a mismatch. It wasn’t so much David v Goliath as David v Goliath’s big brother.

Inter Milan were no ordinary football team and Helenio Herrera was no ordinary football manager. But to the surprise of many they finally met their match in Celtic and Jock Stein.

With his slicked back jet black hair and sharp suits Helenio Herrera looked like a man born to manage the money laden Internazionale.He looked every inch a man of style, elegance and wealth.Yet his roots were every bit as humble as the former Lanarkshire miner who would eventually deliver a near fatal blow to one of the most incredible careers in football.

Commonly referred to as an Argentine, Herrera’s only real connection to the South American country was that he happened to be born there in 1910. Both his parents were Spanish. His father was an active trade unionist and anarchist who had crossed the Atlantic in the hope of escaping an impoverished life in Andalusia. But while the long boat journey may have taken him away from his homeland, poverty was not so easy to escape.

With Helenio just a young child the family set off once more, this time Morocco was the destination. Although the family remained desperately poor they were to stay in the impoverished and dusty backstreets of Casablanca throughout Helenio’s childhood years.

It was here, kicking a ball around with friends under the baking north African sun, that the future football aristocrat first fell in love with the game that was to rule the rest of his life. Given such a background it seems only natural that Herrera’s football career would also be nomadic.

His first taste of professional football came as a player in France – where he adopted citizenship – but his career was modest. Certainly no one who had witnessed his performances as a defender for the likes of Stade Francis, Red Star Paris and Puteaux could ever had envisaged that here was a man who would revolutionise football.

But that’s exactly what he did – eventually. His apprenticeship as a manager saw Herrera start his career on the touchline in 1945 at Puteaux but almost inevitably he was soon on his travels once more. During the next 14 years he would manage six different clubs in three different countries – France, Spain and Portugal. His first taste of real glory came at Atletico Madrid where he led the Spanish capital’s second side to two league titles in 1950 and 1951.

In the Spring of 1958 the wanderer arrived in Catalonia. His plan was to mastermind the revival of Barcelona. The Catalans were finding life tough living in the long shadow cast by the scintillating success at home and abroad of the Alfredo Di Stefano inspired Real Madrid. To most observers it was not a plan Herrera needed to transform under-perfoming Barca but a miracle.

It is no surprise then that he would soon be christened ‘The Wizard’ as in his first full season the Nou Camp faithful rejoiced in the capturing of the league and cup double. For good measure the Inter City Fairs Cup was claimed as well. The league title was retained the following season as The Wizard continued to weave his magic. But not everyone was captivated by his spell.

He may have been the son of a anarchist but there was not a hint of his father’s political philosophy in Herrera the manager, an ultra-strict disciplinarian who made no attempt to disguise his contempt for anyone unwilling or unable to conform to his regimented regime. Coupled to this was an arrogance and over-bearing self-belief which inspired and isolated in equal measure. There was certainly some in the press who found The Wizard’s potions hard to swallow and soon there were rumours that the real reason for Barca’s sensational turnaround in fortunes was down to the illegal use of performance enhancing drugs.

Despite capturing two successive league titles for Barca Herrera’s reign was to come to an abrupt end. His achievements as a coach should have made him a King among the Catalans but his arrogant, dictatorial style instead made him a figure equally loathed as loved. As Franco would testify, the Catalans had little time for dictators. In this climate it was inevitable that Herrera would not earn the devotion the success he brought deserved.

The maverick Hungarian genius Kubala was adored by those who worshipped at the Nou Camp but the man regarded as the heartbeat of Barca soon found himself a peripihial figure under Herrera.

Decisions such as this coupled with a barely hidden conceit for the press and rivals meant that Herrera found winning trophies a much easier task that winning friends. Fans were antagonised by his reluctance to play their favourite players and Herrera’s lack of diplomacy meant the media were sharpening their knives in eager anticipation of the slightest fall from grace.

Consequently when Barcelona were humiliated 3-1 in both legs of of the 1960 European Cup semi final by Real Madrid it was an easy decision for the powers at Barca to make Herrera the scapegoat. Despite two league championships in as many years he was sacked. It was a decision the Barca directors would regret much more than Herrera. By the start of the next season Herrera had moved to Italy where he had been lured by club president Angelo Morrati. An oil billionaire Morrati’s dream was to build a club which would wrestle from Real Madrid the title of the most successful football club in Europe. His appointment of Herrera was the moment when that dream started to become a reality

With money no object Herrera and Morrati set out on building a team to conquer a continent. Money obviously helped pay for the finest material, but the real key to success was Herrera, the man who was to become the architect and master builder of a team which would be christened ‘Grande Inter’ – the Great Inter.

With Herrera at the helm Inter soon became the dominant force both in Italy and Europe. Between 1961 and 1967 the Milanese side won three league titles (63,65,66), two European Cups (64, 65) and two Inter-Continental Cups (64, 65). During this period they never finished out of the top three in Serie A.

It wasn’t just silverware they collected though. Their success on the continent ensured the club developed a nationwide fan-base which saw Inter fans springing up in villages, towns and cities across Italy. As the lyrics to the classic Celtic song Willy Maley proclaim, this truly was “…the team all Italy adored”.

Adored as they were, there was also no shortage of critics. In particular those who prescribed to the beautiful game found Inter’s style of football a little too pragmatic. For some purists there was a deep cynicism to Inter’s play and a win at all cost attitude which no amount of trophies could justify. Inter’s reliance on the Catenaccio system may have been shared by many other Italian teams at the time but this ultra-defensive approach would never win any popularity contests.outside of Italy.

Herrera boasted he was the inventor of this infamous defensive system – which roughly translated means ‘the padlock’ – but it had actually been devised by Austrian-born Swiss national coach Karl Rappen back in the 1930s. But while Herrera may not have invented Catenaccio he certainly perfected it. Many Italian sides had adopted this approach but none with anywhere near the success of Inter.

Yet it would be wildly wrong to dismiss Herrera’s Inter as merely a defensive side. Because here were a team more than capable of scoring freely when they chose to do so. Indeed they posed a goal threat from virtually every outfield position, racing forward in rapid, lethal attacks. Herrera was one of the first coaches to utilise his full-backs as an attacking force and this is evident in the fact the magnificent left-back Fachetti scored more than 70 goals during his illustrious career. Like a cornered snake Grande Inter’s natural instinct was to defend, but when the moment came it could also attack with a deadly swiftness.

While Herrera’s tactics on the filed of play were not always to everyone’s liking, his approach to coaching was even more questioned. His training methods and pre-match routines were militaristic in their regimented precision. Players who failed to meet his rigorous standards of discipline, both on and off the pitch, were simply discarded. However good a player you were if you didn’t jump when and where Herrera wanted you to then the exit door loomed.

There were fewer more devoted students of the game and his tactical knowledge was unrivalled.He had file upon file on players and opposing teams. His precocious adoption of psychology and attention to detail on matters such as diet were revolutionary. A master at mind games he would boast his team had often won the game even before they left the dressing room.

He encouraged his players to prepare for matches through meditation and before games he would gather his players in a circle, throw a ball at each one and scream instructions in their faces before embracing each one as they went onto the pitch. His most famous trait involved devising slogans aimed at inspiring his team to further success. In Big Brother style these slogan would be posted around the Inter dressing room.

As manager of Dunfermline Jock Stein himself had travelled to Italy in 1963 to spend time studying Herrera’s methods. Herrera was impressed by the energy of the man from Burnbank who he christened ‘The Big Ant’. Stein’s trip to Italy had been paid for by a newspaper and there is no doubt he took a lot from the experience. Certainly come May 25th 1967 Herrera would be impressed with much more than just the energy of his rival.

While Stein and other Scottish coaches had made their footballing pilgrimage to view Herrera at work critics in Italy branded the Inter coach’s antics and methods bizarre. But however strange they may have seemed the simple fact of the matter was they made Inter the dominant club team in world football.That was of course until Lisbon.

Herrera’s boast that his team often won games before even stepping onto the pitch could so easily have applied to that beautiful day in Lisbon and the pre-match preparations. As Celtic arrived at the stadium to train on the evening before the final they were met by the Inter team just finishing their session. Instead of retiring to the showers the Italian players and their manager congregated on the touchline and there they stayed until Celtic’s practice session ended. It was classic Herrera.

The next day, with minutes remaining to kick-off, the two teams were.standing together in the tunnel, waiting to enter the arena.

The Celtic players couldn’t help but be impressed by their opponents. Athletic and tanned they looked every inch the footballing sophisticates. Jimmy Johnstone commented to his team-mates that the Inter players all looked like movie stars.They didn’t only look the part, they had the medals to prove they had the substance to match the style. For all Celtic’s domestic dominance that season it paled into insignificance in comparison to the achievements of these men who had conquered Europe and the World. It is no idle boast to say most teams would have been beat before a ball had been kicked.Celtic were not most teams.

Bertie Auld’s response to this moment of apprehension and tension has of course gone down in Celtic folklore. His leading of the players in singing ‘The Celtic Song’ as they began the long walk up the tunnel sent not just a message of defiance to Inter but one of inspiration to Celtic. Inter may well have been Grande, but Celtic were also a grand old team to play for.

Stein struck a psychological blow when he got reserve keeper John Fallon to claim the bench nearest the halfway line. This did not impress the Inter officials. It was a small, seemingly trivial act of defiance. But what was clear to all was that this club which had for so long represented the underdog would not now, in its finest hour, be bullied by anyone.

When the players emerged from the tunnel the Celtic players appeared blinking in the sunshine like miners emerging from the bowels of the earth after another shift in the darkness. Stein, who followed his Bhoys out of the tunnel, would have been forgiven for thinking back to his days as a collier. He had come a long way. From toiling underground at Earnock pit to guiding Celtic to the summit of European football. He was close to completing a most remarkable journey.But the giant of European football – Helenio Herrera – stood between him and this majestic peak. Was it really possible?

Of course it was. What happens over the next 90 minutes is written in the heart of every Celtic fan. Indeed of everyone who appreciates and loves attacking football. Stein and Celtic did not defeat Grande Inter. They destroyed them. The scoreline was 2-1 but the reality was that this was a beating which left Inter and Herrera battered and broken. Catenaccio was savaged by what Big Jock described as ‘Pure, beautiful, inventive football’.

How ironic that it was a rampaging full-back who hit the cannonball shot that eventually breached Inter’s resiliant defence. That fine Tommy Gemmell strike was of course followed by Stevie Chalmers late winner. It was a goal which brought justice. It was also a goal that also brought down the curtain on one of Europe’s greatest ever club sides. Grande Inter were no more. It was the end of an era. And in truth it was the end of Helenio Herrera.

The Argentine was sacked. He moved onto Roma and returned to Inter in the mid 70s. He ended his career in 1981 at the Nou Camp, where he had returned to take over a Barca side starved once more of league success. This time The Wizard could not conjure the success the fans craved. He hadn’t lost his magic. It was just that the secret of his tricks had been exposed that majestic day in Lisbon.

What Celtic and Jock Stein achieved in the Portuguese capital was much more than win the European Cup – fantastic achievement that it was. They heralded a new era in football. They were a green and white whirlwind which blew away the football establishment and their old, negative ways. Almost 80 years from the day they were founded to feed the poor in Glasgow’s east end Celtic FC had struck another blow for the underdog. The football world celebrated the end of catenaccio and the victory of football the Glasgow Celtic way.

(written by HumanTorpedo 2006)