| Player Biog |

Standing on the shoulders of Celtic giants

http://www.sconews.co.uk/feature/52942/standing-on-the-shoulders-of-celtic-giants/

Ex-footballer and pundit Charlie Nicholas talks to Richard Purden about his Faith and those he is indebted to

CHARLIE Nicholas was one of the most popular and talented footballers of the 1980s. Starting his career at Celtic, he was soon a target across the border, eventually moving to Arsenal. Since then, Mr Nicholas has carved out a career as a successful football pundit on Sky television.

Despite working in London he regards Glasgow as home and continues to hold the city in high esteem. “I’ve always been in Glasgow,” he explains. “Most people are surprised that’s the case: I work in London but if I don’t need to be there I’m back in Glasgow. I’m born and bred in the city. Yes, some bad things happen but what city doesn’t have that? I love the feeling in Glasgow and the involvement. I like the debates and the football discussions. My two daughters have also got into it.

“There is a fire in the belly of Glaswegians and that is something that I grew up with and throughly enjoyed. I find it an inspiring and truly happy place.”

Mr Nicholas admits he gets ‘stick just walking down the street’ from both halves of Glasgow’s football divide. He remembers vividly the first piece of criticism he received as a professional player: it was from the man he is sharing a stage with later this month, a Celtic great and Lisbon Lion.

“The first person to criticise me was Bertie Auld. He was manager of Partick Thistle at the time. When I went into Celtic Park the next day Billy [McNeill] said to me: ‘I see Bertie had a pop at you.’ My response was: ‘Yes I was quite surprised by that.’ Billy, who was manager at the time, said: ‘Listen, get used to it because I’m going to be giving you a lot of it. Criticism is a sign that people know how good you could be.

If you don’t like criticism then you’re at the wrong club.”

It was a learning curve for Mr Nicholas and his response was to ‘score one of my best ever goals’ against the Jags in the aftermath. The ex-player admits that his life and career was shaped by the Lisbon Lions and other well known Celtic players who taught him about life beyond the game.

He describes his time with them as a ‘gift from God.’ Growing up at Celtic was ‘part of our working class education.’ I used to practice a lot and John Clark would come and watch me. I think he was quite intrigued because I was trying some drills with my left foot and there was not many others doing that. He was very encouraging.

“We had this sofa where players like Tommy Gemmell and Jimmy Johnstone would come in and sit down. Jimmy had retired but he just wanted to be around what was happening at Celtic and he would get involved with the training. There was always a smile and a laugh but they all had this serious side; they would ask you if you understood what it meant to play for this club, what it meant to win the European Cup. They kept the spirit of the Lions around the place.”

Although living in the West End today, he still returns to the streets where he grew up to attend Mass. “I’m a practicing Catholic. I don’t stick it down anyone’s throat but I’ve returned to my old parish, St Gregory’s in the Wyndford. I try to go there most Sundays when I can—sometimes I’m in London but I tend to go back to where I started off. That was the first real church I was brought up in and I’ve started to go a lot more. It’s never changed.

Some of the priests are older or have passed, and the parish has changed in terms of the people that go but being a Catholic and the idea of what Celtic stood for was a true blessing for me.”

Significantly, Mr Nicholas attributes his own understanding of Celtic to another much-respected club hero. “My mentor was Danny McGrain—he looked after me like a father figure. Like plenty other young Celtic players you would get caught up in the emotions of Irish history and the rebellious nature. The Rangers boys I grew up with from the barracks [in Maryhill] went through that too. We didn’t do it in front of each other—some of the songs would attract a glance of the eye from a player like Danny as if to say ‘why are you singing that?’ It was funny but there was a point of principle, we understood and respected that it wasn’t for them.

Danny used to pick me up because I wasn’t old enough to drive. From Monday to Friday he would fit in at least three hospital visits or supporter functions. After training he would ask me what I was doing. My response was not a lot. He’d say, ‘ok, we’re going on a hospital visit, this guy’s lost a leg in an accident.’

“We would turn up and you’d see someone for an hour. I’ll tell you, it’s not easy when you walk into a situation like that but Danny would be straight over to talk to the patient, answer any questions about himself and the fabric of the club. I would sit there and listen to him and eventually you would pick up what Celtic really and truly was about.

“In those moments you would come outside and feel cleansed for just going in and saying hello to someone. When I close my eyes and think about what Celtic is, I think of Danny. I can see the statues of Jock, Billy, Jimmy and Brother Walfrid but I also think Danny has had a hand in those values in terms of his teaching and the ambassadorial role he has played at the club.

“Danny McGrain had it all and a true understanding of everything: that’s why he’s still there to this day.”

Significantly, Mr Nicholas’ most treasured memory is a European tie against Ajax playing alongside his mentor and against some of his footballing heroes. “We got a big scalp that night. It was a game of substance and an emotional breakthrough for me. It was the first real scalp we had claimed as side in Europe. I had watched the history up until that point but that night I got to take part in it.”

Terry Neill on going the extra mile to take Celtic’s Charlie Nicholas to Arsenal

Former Highbury manager reveals how a shilling swung the deal, before striker was dazzled by London’s bright lights

By Alan Pattullo

Sunday, 10th May 2020, 11:53 am

https://www.scotsman.com/sport/football/terry-neill-going-extra-mile-take-celtics-charlie-nicholas-arsenal-2848066

How I signed Charlie Nicholas

Such sensitive treatment of a wayward superstar perhaps helped facilitate Neill’s recruitment of a player who, in the summer of 1983, was cast as the new George Best – Celtic’s Charlie Nicholas.

No one truly expected Arsenal to win the race for the hottest property in British football in the face of competition from Liverpool and Manchester United. But Neill went the extra mile to secure the signature of a player who had scored 48 goals for Celtic the previous season.

While Liverpool, already blessed with Kenny Dalglish and Ian Rush, never appeared to truly pull out the stops for Nicholas, Manchester United, whose manager Ron Atkinson was a bit of a flash Harry, looked the likelier destination for the striker.

“Ah, but I had a few ‘mafia’ pals up there in Glasgow,” explains Neill. “I knew what Charlie was eating for breakfast, lunch and tea. What he was doing, where he was going.

“I enlisted a bit of help and advice from Jock Stein, who became a great friend over the years. I had a few conversations with the Big Man.”

Stein, the then Scotland manager, seemed to act as Nicholas’ unofficial agent, specifically in the days prior to a game with England at Wembley in May 1983, when the Scots were based at a hotel in Hertfordshire.

“I rang Jock at the hotel and I said: ‘would it be possible to have ten or 15 minutes with Charlie if I popped up to the hotel?’ I was living in Hertfordshire then and the Arsenal training ground was just 15 minutes down the road from their hotel. Everyone knew there were three of us vying for Charlie’s signature. And Jock said, ‘you know what, you are the only one from any of the clubs to have the decency to ring me’.”

Atkinson had already visited the hotel – uninvited. “Jock said: ‘Bojangles was down! He did not even have the decency to give me a ring!’” continues Neill.

“Jock was brilliant. He said: ‘you can pick up the boy at 9pm at the back of the hotel. I know your training ground is just down the road – why don’t you take him and show him around there? And you can take him for a lager afterwards – but only one. Have him back at a reasonable time’.

“I was not going to be one to disobey big Jock. You didn’t cross the Big Man.”

With Neill in Indonesia on a club tour, Arsenal secretary Ken Friar travelled to Glasgow to clinch the £750,000 – and a bit – deal between clubs with strong ties at the time.

“Typical of the Celtic board then, they did not hold an auction: the price was the price,” says Neill. “Ken took a shilling out of his pocket and put it on the table and said, ‘gentlemen I think this takes our bid above the others’. He swears to me to this day that they took it!”

Of course, Neill is too much of a gentleman to exhibit any sense of wishing the deal had in fact collapsed. But it’s true that his fortunes – including, indeed, the premature termination of his managerial career – were very much wrapped up with Nicholas’ struggles in London. By the time the striker had scored his first league goal at Highbury– in January the following year – Neill was already gone, following a run of four successive defeats.

“He was a good lad, who trained well,” says Neill. “But maybe it was a case of the bright lights of London…

“My wife Sandra has just reminded me of the first time she met him. And Charlie – cheeky Charlie – said: ‘you must have been a good-looking girl when you were younger!’”

“I felt I was harshly treated at Celtic,” Charlie Nicholas

By Editor 31 December, 2021

“I felt I was harshly treated at Celtic,” Charlie Nicholas

There was great excitement in Aberdeen on Hogmanay 1987 as the rumour that Arsenal striker Charlie Nicholas was signing for the Dons swept through the city. Then later that evening as the Bells approached the signing was announced live on BBC Scotland from the stage of his Majesty’s Theatre.

Nicholas, once the darling of the Celtic support, had rejected an opportunity to return to Parkhead and instead was heading to North East to play for Ian Porterfield and there have been few signings made by Aberdeen that caused such excitement as that of the former Celtic star. Aberdeen paid Arsenal a transfer fee of £400,000 for the striker.

: New Arsenal players Charlie Nicholas (r) and goalkeeper John Lukic pictured with manager Terry Neill on the Highbury pitch after their summer moves from Glasgow Celtic and Leeds in July, 1983 in London, United Kingdom. (Photo by Murrell/Allsport/Getty Images/Hulton Archive)

Speaking to the official Aberdeen FC website, Nicholas looks back at his two-and-a-half years playing for the club and makes reference to his departure from Celtic in the summer of 1983 and revealed that the way he was treated by Celtic at the time resulted in him opting to sign for Aberdeen and not Celtic on this day 34 years ago.

Nicholas had fallen out of the picture at Arsenal but the Gunners boss George Graham wasn’t keen on selling him to a rival club in England. Nicolas looked at options in France and spoke to Aberdeen chairman, Dick Donald, who had a few months earlier sold his star player Joe Miller to Celtic, and had also spoken Celtic manager Davie Hay about a return to Paradise.

And not only does Nicholas not regret snubbing Celtic in 1997 he actually regrets leaving the Pittodrie club to return to Parkhead two-and-a-half years later.

Nicholas, who turned sixty yesterday, scored 36 goals for Aberdeen and struck up a decent partnership with Hans Gillhaus, much as he had done at Celtic in the early eighties with Frank McGarvey. In an interview in Red Matchday Magazine (presumably meant to have been published for the now postponed visit of theRangers, told the story of how he ended up signing for Aberdeen.

“I was at Arsenal and it was clear I wasn’t in George Graham’s plans. I was never a guy who would hang about if I didn’t feel wanted. I have never been like that. I don’t see any merit in that for anyone.

“I was sent all over the place with Arsenal reserves and George even sent me away with the youth team. I was even sent up to Cambridge University to sit on the bench. It was clear my Arsenal career was over. There was no point in picking a fight, my time was up.

“So when Aberdeen came in for me I went up and met the chairman, Dick Donald. I met him in a hotel in Aberdeen and I was really impressed with him as a person and his ambitions for Aberdeen.

“It was a few days before New Year when I went up. Dick was a gentleman and I was impressed with his plans and ambitions for Aberdeen. I said give me a couple of days to think about things but I did say I wasn’t sure about coming back to Scotland,” Nicholas stated.

“If I was being honest I wasn’t really thinking about going back to Scotland before I joined Aberdeen”, Nicholas admitted. “Celtic were interested. There was an approach through Davie Hay to see if I would be interested in going back?

“I would have thought about it although I felt I was harshly treated at Celtic when I left. I was basically booted out the door and told that I had asked for a transfer, which was never the case.

“I then went to France and I had always wanted to play abroad. I went to Toulon, who were in the French top-flight at the time. I flew out with the Arsenal secretary Ken Friar and we had agreed a deal with them but then George blocked it. Brian Clough then came in for me to take me to Nottingham Forest and Jim Smith tried to get me to Queen’s Park Rangers and Newcastle but George wouldn’t allow those moves either.

“George Graham wouldn’t have a meeting with me,” he added. “I had to go to Ken Friar but he said it was up to the manager to agree to a deal for me. George wouldn’t let me resurrect the deal with Toulon or go to England so I just told Ken that I wanted to go to Aberdeen.

Charlie Nicholas celebrates his goal in the 1982 League Cup Final win over Rangers

“Aberdeen was a deal that George wasn’t adversed to. So I decided that was where I wanted to go and I phoned Dick on Hogmanay to tell him that I was going to Aberdeen and that is when the story began to break.”

“I think the Aberdeen fans were happy I signed for Aberdeen. It showed the club they still had a burning ambition and the pull to sign players from the English top-flight. I just wanted somewhere to play and enjoy my football. I wasn’t even thinking about Scotland recalls or anything like that.

“I just wanted to get back to playing and enjoying my football again. My time at Aberdeen was amazing. I was there for just over two and a half years. The one thing I always appreciated about the club. They were always good to me. They also had to be patient when I signed because it took me a few months to get fit and up to speed.

“I knew it would take me the best part of two or three months to really get fit. When you are not playing and it really does setback you. Scotland was also so much faster and physical than England. I knew that and the club accepted that. I have to say the fans were also great and were patient with me as well. “At Arsenal we won the cup and had the bus trip the next day and then the celebrations at the town hall and there were 100,000 people there.

“It was similar when we won the two cups at Aberdeen and especially the Scottish Cup. The number of people who were out on the streets of Aberdeen was amazing. It just showed what Aberdeen as a football club and a city could deliver if and when they were successful. I also knew I was walking away from all that.

“When the team came out on the balcony the fans were brilliant to the team and me and I really appreciated it. Looking back with hindsight, I know I should never have left Aberdeen when I did,” Nicholas stated.

He of course left to return to Parkhead in the summer of 1990 after scoring the decisive goal in the Scottish Cup Final penalty shoot-out against Celtic.

Charlie Nicholas: Who is the real man behind the Champagne Charlie myth?

8th April 2017

https://www.heraldscotland.com/sport/15212219.charlie-nicholas-real-man-behind-champagne-charlie-myth/

WE ALL have a certain amount of vanity,” Charlie Nicholas tells me. “I don’t have very much of it, although people find that quite strange.”

He walks into the restaurant in Hyndland, in the west end of Glasgow. Silver hair, sparkling eyes, white teeth and smiles, a bomber jacket and jeans, sharp shoes, discreet ear stud, looking good on his 55 years. He sits down and orders a ginger beer, and tells me he’s not much of a storyteller and then tells me stories for an hour. He is charming, self-deprecating and, as it goes, fairly lacking in vainglory.

There is, I suppose, a generation now who know Charlie Nicholas as that bloke on Soccer Saturday amiably mangling the English language as he tells you what’s happening in an English Premier League game that you can’t see.

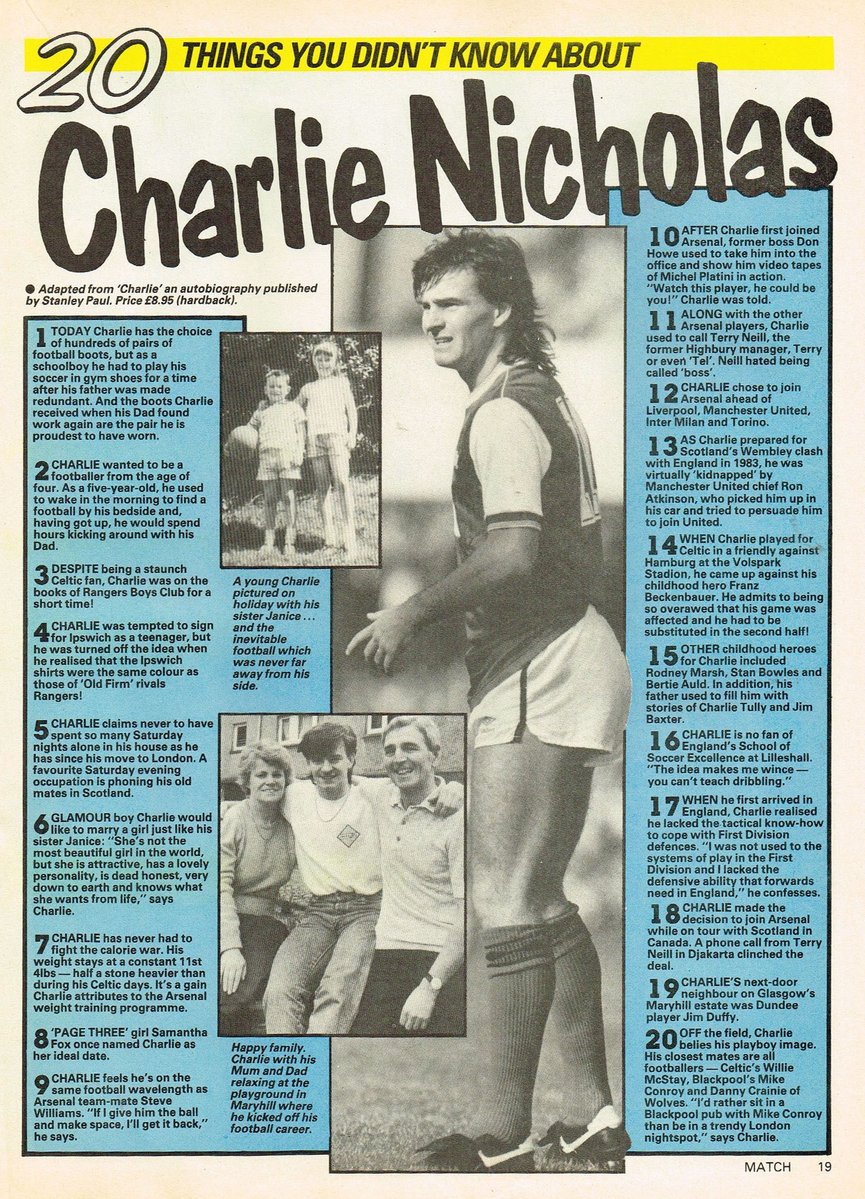

But for those of us who remember him in his pomp he remains Champagne Charlie, the boy who scored nearly 50 goals for Celtic in a single season, the Scot who chose Arsenal over Liverpool and never lived up to his huge potential unless it was for wine, women and song.

Actually, not the last of the three. He never made a record, although he was asked. “When you’ve been caught doing photographs with Page 3 models in your bare underwear I think that’s enough to humiliate you,” he tells me. But he did once make the cover of the NME back when the NME really was the NME, not a fanboy freesheet. He’s still very proud of that.

These days Nicholas is paid to opinionate and he’s happy to do so. In our time together he’s keen to speak up for the newish Hearts manager Ian Cathro (“He is creative. Will he ever be a top manager? I don’t know, but I’m very intrigued in what he talks about”), he will mention that he’s not a big fan of the current Celtic captain Scott Brown (hardly news, he admits), or of Chris Sutton’s new role as pundit cum controversialist. “I don’t see too much method in his breakdown,” Nicholas says using a typically Nicholasesque bit of wordplay. “I find that old-school bullying.”

But, really, it’s how the man he is looks back on the man he was that I’m interested in. Nicholas is a married man with two grown-up daughters. He has lost loved ones (his father, his brother and his sister) and knows that life is not a never-ending night out at Stringfellows (although, to be fair, he once said he was always more at home in the exclusive members’ club Tramps).

There would have been a time when a ginger beer would not have featured on the menu. “The lazy headline was Champagne Charlie,” he says. “I got the reputation of earring and no socks. In those days we were open with the press boys because they trusted us. We could go for a drink with them, whereas now everything is scrutinised. At that time there was Frank McAvennie and Mo Johnston. We were all a bit maverick. The only harm we ever did was probably to ourselves, our own reputation.”

Before that he was a Celtic boy and a Celtic Boys Club boy.

He spent his earliest years in Cowcaddens (“It’s actually the motorway now,” he says) before the family moved to Maryhill where he grew up next door to current Morton manager Jim Duffy in a community that had an equal measure of Rangers and Celtic fans. His mother was a Protestant who converted to her husband’s Catholicism. “It was quite a big step, which proved her determination.”

Nicholas and his mates – three Rangers and two Celtic fans – would go to the Old Firm derbies together. “We used to get the 61 bus to Celtic Park and the three Rangers fans would get off in the town to get the 64 to the Rangers end, then we would meet them back in Maryhill.”

The first game he was taken to was Celtic against Leeds at Hampden in the European Cup semi-final of 1970, sitting on his dad’s shoulders in a crowd of 130,000. Nicholas’s hero was King Kenny, and from an early age Nicholas only had eyes for the game. “All my stories were about football. They must have been so boring for the teacher.”

He wasn’t very academic, Nicholas admits. He was offered a job in a garage the day he was to sit his English exam. He didn’t bother with the exam. He was a car mechanic for four months before football took over.

Nicholas made his competitive Celtic debut while still a teenager against the mighty Stirling Albion on September 9, 1980, scoring twice. There were many more goals to come.

What does he remember best? His first goal or his first kiss? “By a mile, first goal.” Does he even remember his first kiss? “She was taller than me, dark hair. How can you forget a Sheree from Ruchill? Up by the canal. I was a bit shy then.”

That would change, of course.

At Celtic he’d come under the wing of Danny McGrain. McGrain would pick him up and drop him off every day. “Danny was born and bred in Drumchapel. He knew what hardcore living was.”

For him McGrain is the greatest Celtic man of all time. “Not the greatest Celtic player,” he adds, but “as a man, as a Protestant who came into the fraternity. Danny gave three days a week to charity.”

He speaks of McGrain with great affection. His mentor, he says. “Danny educated me,” he says, recalling how he would be dragged into hospitals to visit fans. “He was determined that we should always do that. That kept your feet on the ground, your humility, your understanding of working-class society.”

And yet Nicholas and McGrain were cut from different cloth. As players and as men.

McGrain hid in plain sight. Nicholas? Well, hiding away was never part of the process. That said, the Nicholas legend almost ended before it began. At the age of 20 he suffered a broken leg and, as he points out, “in those days a broken leg was potentially career-threatening”.

It was during a friendly against Morton. An accident. “The bottom of my foot was dangling so I could tell it was broken. But they didn’t phone an ambulance or anything.”

The club’s doctor took him in his car. “And you had to say three Hail Marys and three Our Fathers before he would start the car. I was trying to hold my shin together in the passenger seat thinking: ‘What the hell is going on?’”

He worked on his recovery in Celtic’s gym, “a pokey little dark hole in the Celtic Stand. No lights, no nothing, cheapest weights you could ever believe”. It’s possible you can hear his disdain for the club’s parsimoniousness which would eventually drive him away.

Before that, though, back on his feet he scored four goals at East End Park in a 7-1 League Cup rout over Dunfermline near the start of the 1982-83 season and never looked back. He bagged 48 goals that season, was named the Player of the Year and even scored (“one of my all-time favourite goals”) in a European Cup win against an Ajax side that contained Johan Cryuff; a victory that remains his fondest memory of his Celtic years. That said, all Celtic won that season was the League Cup.

And already he was being linked with a move away from Glasgow. There was interest from Manchester United – but he wasn’t impressed by the club’s then manager Ron Atkinson – from Italy, from Liverpool, led by his hero Kenny Dalglish, of course, and even Spurs, then the team of Ossie Ardiles and Glenn Hoddle (“the best British player I ever played against. And I include Dalglish in that”). This is the point where I show him my Spurs beanie. He is not impressed.

Nicholas, instead, opted to go to “boring, boring” Arsenal. He has not a bad word to say about Arsenal the club. The team, not so much. Moving to Highbury was, he is not afraid to admit, a mistake. “The Arsenal style didn’t suit me. I should have went to Liverpool but would I have got a game with Dalglish and Rush? I don’t know.”

The Arsenal of the early 1980s were a far cry from George Graham’s stuffy title winners of the early 1990s, never mind Wenger’s Invincibles. In his five years at the club Nicholas would pick up a League Cup winner’s medal and a rather more celebrated reputation as one of football’s wild boys.

There’s a small irony in Nicholas’s Champagne Charlie tag in that Graham’s title-winning Arsenal side of the early 1990s had a ferocious drinking culture (which would see Tony Adams end up in jail and Nicholas’s Soccer Saturday colleague Paul Merson go wildly off the rails). And the truth is during his first year at the club Nicholas’s main problem was loneliness.

“I loved London – I still love London as a place – but I found it incredibly lonely. My teammates were predominantly settled down and married.”

And so he’d spend his weekends often not in London but in Wolverhampton or even Blackpool. How long would that take, Charlie? “I used to get up in two and a half hours.” What? Two and a half hours?

“And then drive down Monday morning to make training. How I did it I’ll never know.”

In Birmingham he and his former Celtic teammate Danny Crainie, then at Wolves, were chased from a pub by a gang of black Birmingham City fans who called themselves the Zulus. “I was faster than Danny but Danny was away quicker than me.”

The wrong pub is still a pub of course.

“I wanted to go out and party. I was 21 and single,” he says in his defence. He never stinted on training. It was just that a glass of wine made life less lonely.

Eventually he found his feet socially and things kicked up a gear. He’d hang out in the bars of Highgate with members of Spandau Ballet. (“A couple of them were Arsenal fans,” he tells me. Another reason to not like them, I point out.)

After training he’d head into London and pop into a bar in Mayfair called Blondes to see if George Best was in. The bar’s owners used to give Best £300 if he showed his face.

“In the end I got quite pally with George. George was the most timid superstar you’ve met in your life. He was insecure. No real ambition about being seen or heard. He used to just sit there and drink. His head would end up in a plate of chips swimming in vinegar. He would wake up like that and still look as handsome as hell and these superstar women were hanging about.

“My god, the women who used to come around him … And sometimes I got the benefit of that.”

Well, yes. In his time in London Nicholas was linked with Suzanne Dando, former Olympic gymnast, Janis Lee Burns, the Cadbury’s Flake girl, and even, she later claimed in a tabloid kiss-and-tell, Thereza Bazar, better known as half of the pop duo Dollar. Was that the case, Charlie? “Yeah,” he says, looking, if it’s possible, slightly abashed. (In true tabloid style Theresa claimed: “He certainly scored a hat-trick with me that night.”)

Which reminds me, that picture of him in his “bare underwear”. It’s all over the internet if you google him. Charlie in a pair of the briefest budgie-smugglers you’ve ever seen. I’ve kindly printed off a copy to show him. “That’s shambolic,” he laughs. “My daughters absolutely cane me when they see that. I’d been in London for two weeks and I was offered quite a bit of money.

“That was done with a couple of Page 3 girls. Good memory of it in some departments. Not so much in others. I’ve probably still got that underwear.”

All of this wouldn’t have been a problem, of course, if Arsenal were winning anything. But, that League Cup victory apart, that was never on the cards. And so the Champagne Charlie tag became a rock to beat him with.

Here’s the thing, though. George Best in the end would eventually drink himself to death, while at one point Frank McAvennie ended up bankrupt and drugged out (this is in the days before the Saltire boiler ads, obviously).

The truth is Charlie Nicholas’s biggest failing was that he never quite fulfilled his potential. After Arsenal he came back to Scotland to play for Aberdeen, before heading back to Celtic and then finishing his career at Clyde. He scored goals everywhere but never enough and never enough to win much of anything.

He stopped playing in 1996 and has spent the last two decades developing his career in the media. And pursuing various business interests in Glasgow bars. “They didn’t finish particularly well with my other partners,” he admits (one former partner ended up in court for forging Nicholas’s signature). He’s now working on a new clean energy business.

He still loves football, he says. Given everything, can Nicholas say the game has given him any lessons for life? “Absolutely. We sometimes had a saying. We used it a lot in London. ‘It’s nice to be important but it’s important to be nice.’ Fairly simplistic. I’m a fairly simplistic guy. In more ways than one.”

He laughs at himself as soon as he says it. That’s one ability time has never robbed Charlie Nicholas of.

Legends of Scottish Football with Charlie Nicholas and Bertie Auld takes place the Glasgow Royal Concert Hall on Thursday.